lobally,

in boxing, Muhammad Ali has been and probably always will be the yardstick for

greatness. Down Under, it’s

Tony Madigan, whose two bouts with Ali continue to fill lovers of the Sweet

Science with awe. What Australians have unfortunately forgotten, however, is

that Madigan also fought Sir Henry Cooper, came back from a devastating car

crash in Germany to train under Cus D’Amato with Floyd Patterson and José

Torres at Stillman’s, was guided by Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney, inspired a

great Australian novel and was challenged by Rocky Marciano and Archie Moore. And he once challenged Ali to a

professional fight.

However, when Ali and Madigan did meet for a third and last time, in

the Doncaster Hotel in London on December 8, 1980, it was merely to shake hands, exchange compliments and shape up to one another – Ali was 38 and Madigan 50. “Damn! Tony Madigan!”

Ali declared, admiring the Australian for still looking to be in good

enough condition to go another three gruelling rounds.

The death of Ali gave Australians the opportunity to

reflect on the fact that one of their own was one of only 10 men to have faced The

Greatest of All Time, post age 16, in the ring more than once (only two, Joe

Frazier and Ken Norton, fought Ali three times). Indeed, Tony Madigan was

one of only five fighters to have gone, as it were, “the distance” with Ali –

though in Madigan’s case, admittedly, this was in three-round light-heavyweight

amateur bouts, when Ali was still a Louisville teenager. Madigan forced close

decisions - when Ali was known as Cassius Marcellus Clay – in both the Golden

Gloves intercity match between New York and Chicago in Chicago on March 25,

1959, and less than 18 months later in the Rome Olympic Games semi-final on

September 3, 1960 (Ali went on to claim the gold medal).

With Bing Crosby

rooting for Ali in one corner and Sydney sportswriter Ernie Christensen

seconding for Madigan in the other, the judges gave the fight 60-57 to Ali, but

the hooting of the crowd at the announcement of the decision showed that few

others in the Palazzo della Sport agreed with them. And Christensen wasn’t the

only journalist to feel Madigan had been robbed.

utside

the ring, Madigan’s great sporting passion was rugby union. In Sydney he had

played the game at Christian Brothers College, Waverley, for the famous clubs

Randwick (14 first-grade matches, two tries, 1950) and Eastern Suburbs (1951, 1957

and 1963), in London for the Harlequins in 1953 and in New York from 1960-62

for the Westchester club.

He generally played as a breakaway or No 8 but in the

US was also called on to play flyhalf in 1962. It was as a breakaway that he

represented the US’s Eastern Rugby Union against Quebec in Montreal in 1960,

when he won Westchester’s Most Valuable Player Trophy (presented to him by the

New York Giants wide receiver Kyle Rote). After getting five stitches inserted

in his cheek after a bout with Kyogle’s Athol McQueen in 1964, Madigan said,

“I’ve been hurt worse playing rugby.”

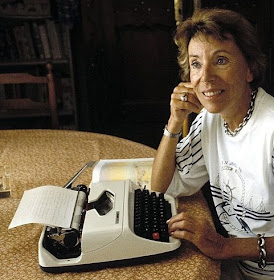

Madigan’s life story is far more

involved and interesting than other online sources might have us believe. For one thing, no biography mentions he had a critically acclaimed novel written about

him. In the rich pugilism-meets-art tradition of Rocky Graziano’s 1955 Somebody Up There Likes Me and Jake

LaMotta’s 1970 Raging Bull – if perhaps

less gory – Madigan was the protagonist (as a thinly disguised “handsome

drifter” Charlie Dangerfield) in T.A.G. Hungerford’s Shake the Golden Bough (1963). He was also a TV star, acting with

Peter Graves in the “Australian Western” Whiplash,

screened in the US in 1961.

Madigan’s life story is far more

involved and interesting than other online sources might have us believe. For one thing, no biography mentions he had a critically acclaimed novel written about

him. In the rich pugilism-meets-art tradition of Rocky Graziano’s 1955 Somebody Up There Likes Me and Jake

LaMotta’s 1970 Raging Bull – if perhaps

less gory – Madigan was the protagonist (as a thinly disguised “handsome

drifter” Charlie Dangerfield) in T.A.G. Hungerford’s Shake the Golden Bough (1963). He was also a TV star, acting with

Peter Graves in the “Australian Western” Whiplash,

screened in the US in 1961.

uite

apart from facing Ali twice, he also fought the great British heavyweight Sir

Henry Cooper (“Our ’Enry”, who also met Ali twice), was challenged to a

professional fight by Archie Moore, trained for three years at Stillman’s in

New York with Floyd Patterson and José Torres under Cus D’Amato, and was

managed by the legendary Eddie Eagan. Madigan lost his father when was just

eight, took up boxing at that age, and fought more than 250 bouts, from

Greymouth, New Zealand, to London and New York, from Helsinki to Chicago and Toledo, Ohio, and from

Mexico City to Rome and Vancouver.

uite

apart from facing Ali twice, he also fought the great British heavyweight Sir

Henry Cooper (“Our ’Enry”, who also met Ali twice), was challenged to a

professional fight by Archie Moore, trained for three years at Stillman’s in

New York with Floyd Patterson and José Torres under Cus D’Amato, and was

managed by the legendary Eddie Eagan. Madigan lost his father when was just

eight, took up boxing at that age, and fought more than 250 bouts, from

Greymouth, New Zealand, to London and New York, from Helsinki to Chicago and Toledo, Ohio, and from

Mexico City to Rome and Vancouver.

Madigan boxed for both Australia and England, won an Olympic

Games bronze medal, was fifth in two other Olympics, and won two Commonwealth

Games gold medals and a Commonwealth Game silver. It was only in the last two years of his boxing career, which ended in 1964, that his success rate fell

below 95 per cent. He missed a year in the ring after suffering serious injuries in

a car crash which claimed the life of a friend, Helen Stokes-Smith, in Germany

in 1955.

On top of all this, in March 1963, livewire New Zealand-born promoter Harry Maurice Miller returned to the idea of offering

Muhammad Ali $US25,000 and 25 per cent of all film and TV rights to come to

Sydney and fight Madigan at The Stadium (built by Hugh D. McIntosh in 1908 to

stage the Boxing Day showdown between Jack Johnson and Tommy Burns, from which

Johnson emerged as the first African-American world heavyweight champion). Miller

had taken over promoting The Stadium and he offered Madigan £6000 (half what

Ali was to get) to turn professional. It was not the first time this idea had

been floated by Miller – in late 1960, Ali had only just turned pro in the immediate aftermath of the Rome Olympics, and Madigan was still overseas anyway. But the 1963 proposal was the first and only time Madigan was

very seriously tempted to fight for money. Bill Faversham, back then a member of

Ali’s Louisville Sponsorship Group and Ali’s first manager, looked at the offer and just as promptly knocked it back.

ntony

(not Anthony) Morgan Madigan was born in Sydney, on February 4, 1930, but grew

up in Bathurst, where his father, Kendall Morgan Madigan (1908-1938), was the hospitals

oral surgeon and his Kalgoorlie-born mother, Elsie Maud (1911-1983, née

Loydstrom) a dental student. The couple had married in Sydney on July 16, 1929,

and Tony came along seven months later. Maud Madigan moved to live with her

in-laws in Mosman, Sydney, in 1935 while her husband continued his dental studies

at the University of Alberta, Canada. Mrs Madigan later became a dentist herself,

when she and her two sons lived in Ashfield, Sydney in the 1950s and early 60s

(when Tony was a car salesman and younger brother Mark drove taxis). The family

had moved to West Maitland in October 1936, where Kendall Madigan, now in

private practice, became embroiled in a nasty slander court case with the

father of a young patient. Madigan and a government medical officer won the

case, being awarded £100 each (a tenth of what they had claimed) but at a huge cost.

A little more than five weeks after the finding was handed down, a cancer-ridden Kendall Madigan died, aged just 29, in a private hospital at Darlinghurst, on June

3, 1938. Tony was eight. That same year, Tony took up boxing.

Tony Madigan attended his father’s old school, Christian

Brothers College, Waverley, and followed his father’s example by excelling

there in a range of sports, including boxing and rugby. He was the school’s boxing

champion for four years, before leaving in 1948, intending to follow his

parents into dentistry.

In the intermediate amateur boxing ranks, he first

worked out of Ern McQuillan’s gym in 1949 and won the NSW middleweight title at

that level. Madigan made such an early impression that he came under

consideration for the 1950 Auckland Empire Games. He was coached by former Australian

champion Hughie Dwyer, whose son John had been at Waverley College with Madigan.

Hughie Dwyer, seen below right with Madigan, came from Newcastle and was regarded a one of Australia’s finest

defensive boxers and was a champion at lightweight, welterweight and

middleweight. He retired undefeated from the ring in 1927. Sadly, he did not

pass on his defensive skills to Madigan, who in later years regretted not being

able to resist a natural impulse to attack in his two clashes with Ali.

adigan became

Australian middleweight champion in Brisbane in 1951 and was selected to

represent Australia as a middleweight at the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games.

Madigan was ranked No 5 in the boxing team, however, so was not on the funded list and

had to raise the £750 himself to make the trip. Friends and admirers paid the

money to guarantee Madigan got to Finland, but to pay it all back Madigan went

on barnstorming country tours, holding BBQs and giving exhibitions there, in

gyms, at his old school and in the Sydney railway workshops.

The Australian boxers prepared for the Olympics at the

famous South African Joe Bloom’s West End Cambridge Gymnasium, close to

London’s Piccadilly Circus (Madigan, below, is the overawed young fellow second from right). Given Madigan had only had 15 fights leading into

Helsinki, and was about to face boxers with more than 200 bouts under their

belts, the short time he spent under Bloom was of limited benefit. As well, Madigan

injured his left hand soon after arriving in England, and injured it again when

he got to Finland. Floyd Patterson won the middleweight gold in Helsinki and

Swede Stig Sjölin, who had eliminated Madigan, took one of the bronzes.

Madigan decided to stay on in Europe. He hitch-hiked back

to England, felling trees in Sweden to cover travel expenses. In London, he

toyed with returning to dentistry studies, this time at Cambridge, but elected

to continue dislodging teeth his normal way. He joined the Fulham Boxing Club

while working as a broker for an Australian importing and exporting company in

London (seen in his office below left). On April 24, 1953, Madigan lost to Henry Cooper in the British light-heavyweight

final at the Wembley Pool. Still, he won Irish and London titles and

represented England five times that year, including in a match against Wales in

Cardiff, and also represented London in Amsterdam.

In 1954 Madigan became the

first Australian to win a British title, taking out the light-heavyweight

division at the Royal Albert Hall. The win earned Madigan a nomination for the

British team for the Golden Gloves in Chicago and, along with his English base,

ensured Madigan was on the funded list for the Australian team to compete at

the British Empire and Commonwealth Game in Vancouver in July-August 1954.

Madigan was favoured to take gold, but had lost form even before leaving

London. In Canada, lumbered at 24 with being captain and coach of the

Australian team, in the absence of trainers and seconds, he lost the light-heavyweight

final to Johannesburg’s Piet van Vuuren (1931-2008).

isillusioned

by his Vancouver experience, Madigan took a brief look at the US boxing

scene in September, and promptly announced he was retiring. Madigan returned to

England but at the end of 1954 gave up his London job to work in Germany. He was

out of boxing throughout 1955 after surviving serious injuries in a fatal car

crash in Bavaria on January 17 that year. He was living in Germany at the time,

selling encyclopaedias for a Rhineland publishing company, and was driving a

23-year-old Sydney friend, Helen Stokes-Smith, to the ski fields in the south

of the region. Madigan knew Helen through her father, the retired Sydney

Stadium fight doctor Kenneth Stokes-Smith, of Darlinghurst, a close friend of

the publisher Ezra Norton. Madigan swerved to avoid a truck parked on the icy

road, the car slid out of control and Helen was killed.

In 1956 Madigan went back to England and to the ring in

London, but suffered a cut eye in an elimination bout in the British

light-heavyweight championship. Madigan returned to Sydney to win a place on

the Australian team for the Melbourne Olympic Games. A bout of debilitating

shingles just before the Games didn’t help his cause, and he lost to Lithuanian Romualdas

Murauskas (in action against Madigan above), who went on to take out a bronze medal. Madigan later described the

Eastern Bloc boxers he met in both Helsinki and Melbourne as “crude but

effective”.

In 1957 Madigan regained an Australian title, at light-heavyweight, after a gap of six years. He went on to represent Australia at the

British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff in July 1958. A lack of

planning and preparation (not to mention competition) had seriously handicapped

Australian boxers at previous Games, but this time they found a place to train

in a dingy gym above a fruitshop in Cardiff’s markets. Madigan went on to beat Dublin-born

Augustine Robert “Ossie” Higgins (1931-2000), an Ipswich Town soccer

professional fighting for Wales, in the light-heavyweight final. Madigan was

presented with his gold medal by the Duke of Edinburgh.

n his way

back from Cardiff, Madigan won the Diamond Belt as the best individual fighter at

an international tournament in Mexico City on August 9, 1958. There he caught

the eye of the noted American sportsman Colonel Edward Patrick Francis Eagan

(1897-1967), author of Fighting for Fun

(1934), a lawyer who had been chairman of the New York State Athletic

Commission, which controlled boxing in New York, from 1945-51. (Eagan, left, is seen above with Jake LaMotta, right). Eagan simply asked

the Australian, “How would you like to be the light-heavyweight champion of the

world?” With that enticing carrot dangled before him, Madigan signed a contract

with Eagan, with the plan for the Australian fighter to almost immediately turn

professional. Eagan himself had never turned pro, but had sparred with the New

Zealand world heavyweight title contender Tom Henney, as well as Jack Dempsey

and Gene Tunney. Through Eagan, Madigan was to get to know and to be advised by

Dempsey and Tunney.

Eagan was familiar with Australia and its boxers. During a

world tour in 1926-27 he had visited New Zealand and Australia with his Oxford

boxing friend, Scottish nobleman Douglas Douglas-Hamilton (1903-1973), the 14th

Duke of Hamilton and 11th Duke of Brandon, a pioneering aviator who styled

himself on tour as the Marquis of Clydesdale (right). Douglas-Hamilton was

a boxing Blue and Scottish amateur champion.

Eagan was familiar with Australia and its boxers. During a

world tour in 1926-27 he had visited New Zealand and Australia with his Oxford

boxing friend, Scottish nobleman Douglas Douglas-Hamilton (1903-1973), the 14th

Duke of Hamilton and 11th Duke of Brandon, a pioneering aviator who styled

himself on tour as the Marquis of Clydesdale (right). Douglas-Hamilton was

a boxing Blue and Scottish amateur champion.

In Sydney on July 29, 1926, Eagan gave

away five stone and still TKOed the giant 1922-23 Australian heavyweight

champion (6ft 11in, 18st), Sydney cheesemaker Julíen Désiré Paul Alexi

Brancourt (?-1959). On the same charity night bill was William John McKell

(1891-1985) then Minister for Justice and later knighted and Premier of New

South Wales and Governor-General of Australia. Eagan met up with McKell again

in Sydney in 1944 (McKell, right, is seen below with Eagan in 1944).

Eagan flattens the Sydney giant Brancourt

Brancourt shows off his size.

Eagan is the only person to win gold medals at both the

Summer and Winter Olympic Games in different events, a summer gold in boxing

(light-heavyweight, Antwerp 1920) and a winter gold (four-man bobsled, Lake

Placid, 1932). Like Madigan, Eddie Eagan was a former British amateur champion

who had boxed at more than one Olympics – he also fought as a heavyweight in

Paris in 1924. Eagan, a Rhodes Scholar, had studied at Yale and the Harvard Law

School before going to Oxford.

Eagan watches the first Ali-Madigan fight in Chicago in 1959

Eagan persuaded Madigan to go to New York instead of home

to Australia. The other incentives Eagan offered were to settle Madigan in his

home town of Rye, Westchester County, New York, and arrange for him to train at

Stillman’s Gymnasium at 919 Eighth Avenue, New York City, under the great Constantine

"Cus" D’Amato and alongside world heavyweight champion Floyd

Patterson. D'Amato (1908-1985) was an important influence on Madigan. Born to

an Italian family in the Bronx, D’Amato, below, had discovered Rocky Graziano and tutored

Patterson to be the first Olympic gold medallist to win a professional

heavyweight title.

uring his

three years of training at Stillman’s, Madigan would also spar with future International

Boxing Hall of Famer José "Chegüi" Torres (1936-2009). Madigan had

got to know the Puerto Rican when he represented the US and won a silver medal

in the light-middleweight division at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. Torres was

beaten in the final by the legendary Hungarian László Papp, the first boxer to

win three Olympic golds. Torres went on to be world light-heavyweight champion.

Torres’ literary skills appealed to Madigan: Torres, seen below with Ali, wrote a regular column for El Diario La Prensa and for The Village Voice. He later wrote Sting Like a Bee, a biography of Ali,

and Fire and Fear: The Inside Story of

Mike Tyson.

Madigan, black top, spars with Torres at Stillman's in December 1958

Madigan showed a particular interest in writing and

writers. One American sportswriter said Madigan was the first fighter he’d met

since Gene Tunney to “admit to even a nodding acquaintance with the written

word”. Apart from the great A.J. Liebling, author of the wonderful The Sweet Science, Madigan encountered

in New York the West Australian author Thomas Arthur Guy Hungerford

(1915-2011), noted for his World War II novel The Ridge and the River. Hungerford was inspired by his friendship

with Madigan to write his novel Shake the

Golden Bough (1963). Madigan also befriended the brilliant Greek-born

columnist Taki Theodoracopulos (1936). Saying of Madigan “what a gentleman he

was and is”, Taki wrote in “Sign of the Times” in August 2012: “In 1960 in

Rome, I watched my friend Tony Madigan fighting for Australia in the

semi-finals against an American with the charming name of Cassius Clay. After

three furious rounds we thought Tony had it. ‘It’s going our way,’ said his

trainer, ‘at least a split decision.’ But the decision went Clay’s way. Madigan

never complained; he just shook hands with Clay and told me afterwards, ‘That’s

how sport goes.’ Clay went on to win the gold. You know the rest.”

Madigan, right, spars with world title contender Rory Calhoun.

Madigan retained the Diamond Belt in Mexico City on

September 19, 1959, after reaching the quarter-finals of the US national

championships in Toledo, Ohio, in early April. All this followed his win in the

New York division of the Golden Gloves and representing the city against

Chicago. By early March 1959 at least one “deadly serious” New York sportswriter

was tipping Madigan as another “Great White Hope”, and capable of dethroning

Floyd Patterson as world heavyweight champion. He may well have changed his

mind when at the Chicago Stadium on March 25 Madigan met a then 17-year-old

Louisville schoolboy called Cassius Marcellus Clay. The eagerly anticipated

bout was televised nationally and the fighters won a standing ovation from the

crowd of 7261. Madigan, unfortunately, had been suffering from a virus for days

leading into the fight. He never complained about the close call, but he knew

he hadn’t given it his best shot.

n the way

to winning the New York Golden Gloves title, on February 16, 1959, Madigan made a terrible mess of one Sigmund

Leon Wortherly (1938-), later self-styled “The Black Assassin”. Calling himself a “Killing Machine”,

Wortherly was in later life to write a chilling autobiography, in which he said

“very, very few people have the stomach to kill in cold blood. It takes a rare

and special person to kill in cold blood. I, Sigmund L. Wortherly, am that rare

and special person. I have the ability to kill in cold blood.” Wortherly grew

up in a middle-class family in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem and developed a

fearsome reputation as a gym fighter and was a sparring partner for Paul Pender

and Dick Tiger.

However, he was drawn into a life a deadly crime, admitting to more

than 30 contract killings for the Harlem underworld. He did time with such

infamous thugs as Crazy Joe Gallo, John Gotti, Harold KO Konigsberg and Nicky

Barnes. Wortherly, right, dubbed by police Mr Tough, called himself a “one-man crime

spree”. “I never killed anyone who didn’t deserve it … people often ask me how many people I killed, and I

tell them I don’t know. I lost count.” He was none too tough for Madigan,

though, as a photo prominently run on the pages of newspapers across America showed. Madigan has knocked Wortherly's mouth guard right out.

To pay the rent in Rye and later at 630 East 14th

Street, East Village, Lower Manhattan, Madigan worked as a sales representative

for the Australian branch of British cigarette company Rothmans, and found

additional income as a male model, posing for $40 an hour for advertising

photographer Howard Zieff (1927-2009). Madigan appeared in magazine ads and TV

commercials for cigarettes, beer and men’s products. The modelling work was to

lead to problems when Madigan was persuaded in May 1960 to return to Australia

to try out for the Rome Olympic Games.

adigan

was stunned to find that to get the chance of a rematch with Ali in Rome, he

had to face a stern opponent from outside the ring: The Queensland Boxing and

Wrestling Union. The Australian selectors had already chosen a Queenslander, Ken

Marshall, to fight in the light-heavyweight division at the Olympics, based on

the assumption Madigan was not available and would not be returning home to

stake a claim for inclusion in the Rome team. Some Australian boxing officials

had other ideas, however, believing Madigan was a distinct gold medal chance

and should be convinced to return to Australia. Faced with this prospect, the

QBWU took desperate action. As Madigan had been registered as a

Queensland-based fighter when he was last in Australia, in 1957, the QBWU felt

it had the last say on his eligibility. And it declared Madigan was not only

residentially unqualified to represent the country, but that his modelling

career – for which he’d used images of himself in boxing garb - had violated

his amateur status. Even US sports columnists got in on the act, lampooning the

QBWU’s stand as taking the definition of amateurism in sport to a ridiculous

degree. Sanity eventually prevailed. Madigan arrived in Sydney in late May and

nine days later fought Marshall, on June 6 in Sydney, making mincemeat of him.

Afterwards, Madigan expressed his sympathy for Marshall, saying officials had

placed the Queensland boxer in a humiliating position. Yet Madigan’s return

bout with Ali in Rome had come close to being jettisoned by an overzealous,

narrow-minded committee of faceless men.

he reason

Madigan had not initially expressed much interest in the Rome Olympics was

because a professional boxing career was still a distinct possibility, based on

his 1958 legal contract with Eagan. As well, Madigan was concerned about losing his existing

New York income and his “Loco” apartment (four rooms in a row) in East Village. He had managed to

get a six-month extension on his US visa, probably helped by him filing a certificate

of marriage at Arlington, Virginia, on February 9, 1960, to wed Geraldine Catherine

Kelley (1935-2005) of Rye. The marriage apparently never took place. When New

York sportswriter George McGann interviewed Madigan for the March 9, 1960,

edition of Sir Frank Packer’s Australian

Women’s Weekly, he described Madigan as a bachelor.

Madigan did marry a

German psychotherapist, Sybille (1940-), straight after the Rome Games, in November

1960, and had a son, Kendall Morgan Madigan (named after Madigan’s father) born

in August 1961. (In 1969 Kelley married a Clinton Wesley Rhy, but was known

briefly as Geraldine Madigan).

Madigan made a return to the New York Golden Gloves

tournament in 1962, reaching the semi-finals. He was offered a tempting though

lengthy assignment, being photographed in various tourist spots around the globe, but

in mid-year left New York to return to Australia to win selection for the

Commonwealth Games in Perth. He was made the Australian team’s flag bearer at

the opening ceremony at Perry Lakes Stadium and duly retained his Games title,

beating Ghanaian Jojo Miles in the light-heavyweight final (below). In 1964 Miles

fought Ali in an exhibition during Ali’s African tour.

There had been a mooted exhibition with Rocky Marciano at

the Sydney Stadium in August 1962, when Marciano was in Australia managing a

fighter due to appear at the stadium. But Australian official Arthur Tunstall

ruled out the Marciano stoush because it would have cost Madigan his amateur

status. At the end of March 1963, former world light-heavyweight champion

Archie Moore, then 46, announced in San Diego that he would fight Madigan in the

Australian’s professional debut at the Sydney Stadium in June of that year. Moore

had been KOed in the fourth by Ali (Moore’s former protégé) in Los Angeles just

four months previously. Moore, the only man to have faced both Marciano and

Ali, did have one fight in 1963, and then announced his retirement. Where he

had got the idea of a return to Australia (he had fought seven times here in

1940) is not known, but Madigan’s solicitor Jim Comans knocked back Moore’s

offer as insufficiently attractive, without even consulting Madigan (or so

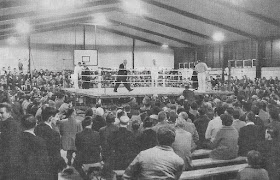

Comans claimed). Instead, on August 14, Madigan fought for Australia in a 6-4

amateur Test loss to New Zealand at the Sydney Stadium.

There had been a mooted exhibition with Rocky Marciano at

the Sydney Stadium in August 1962, when Marciano was in Australia managing a

fighter due to appear at the stadium. But Australian official Arthur Tunstall

ruled out the Marciano stoush because it would have cost Madigan his amateur

status. At the end of March 1963, former world light-heavyweight champion

Archie Moore, then 46, announced in San Diego that he would fight Madigan in the

Australian’s professional debut at the Sydney Stadium in June of that year. Moore

had been KOed in the fourth by Ali (Moore’s former protégé) in Los Angeles just

four months previously. Moore, the only man to have faced both Marciano and

Ali, did have one fight in 1963, and then announced his retirement. Where he

had got the idea of a return to Australia (he had fought seven times here in

1940) is not known, but Madigan’s solicitor Jim Comans knocked back Moore’s

offer as insufficiently attractive, without even consulting Madigan (or so

Comans claimed). Instead, on August 14, Madigan fought for Australia in a 6-4

amateur Test loss to New Zealand at the Sydney Stadium.

reymouth’s

Army Drill Hall was the venue of Madigan’s only fight in New Zealand, 10 days after he'd won his bout in the Test in Sydney. In Greymouth he came up against farmer Johnny Logan, who at 13st 7lb outweighed

Madigan by 8lb, in a six-rounder, which Logan won. Even the locals suspected a “home town decision”.

Madigan, in the right corner, in Greymouth.

In 1964 newspaper magnet Sir Frank Packer sponsored yet another Madigan return to Australia, to make a bid for a record fourth Olympic Games

appearance, in Tokyo. Madigan, now a family man concentrating more on his

business career as a property consultant, was not in prime condition. He stepped

up to the heavyweight division and fought in the NSW championships, but at both

this and national level he couldn’t get past first former Canberran Fred Casey

and then Athol McQueen of Kyogle, who went on to briefly floor Joe Frazier at

the Olympics. Casey also went to Tokyo, as a light-heavyweight. He had beaten

Madigan earlier, in the 1962 NSW championships, and became only the second man

after Muhammad Ali to beat Madigan twice. Casey turned pro straight after the

Olympics. Madigan retired one last time, but did help with the fund-raising effort

for the Tokyo team, by sparring on TV.

Where is he now? A week ago his niece said online: “He

resides in France.” And by all reports he finished up being a very rich man,

still with his body and mind in good shape.