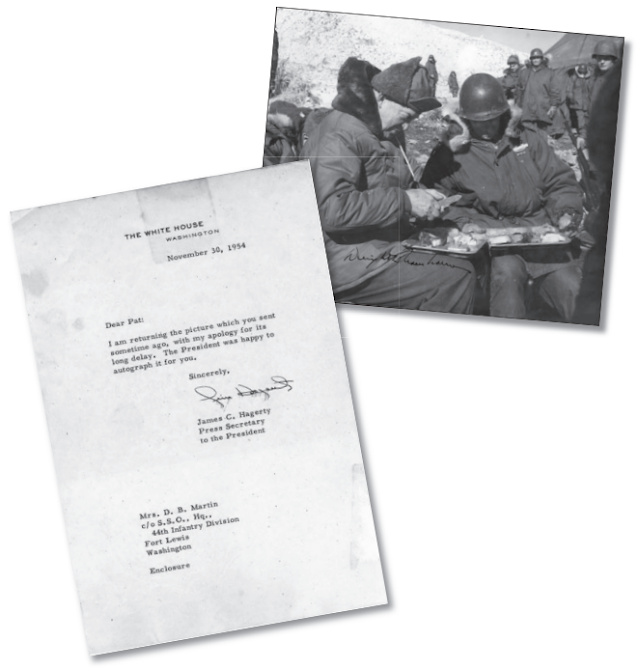

Patricia Corinne Scott was a 21-year-old student when in the spring of 1952 she boarded the American Mail Lines freighter the Java Mail (previously the USS Grafton. a Bayfield-class attack transport) in Seattle and sailed for Tokyo. Not even her family and friends in Battle Ground, Washington, knew she had gone, and wouldn't find out until her byline started to appear in major US newspapers six months later. Scott was following her heart, not her mind, and on sailing out of Seattle would not for one solidary second have thought she was soon going to become a war correspondent in Korea. “Yes,” she recalled in her memoir Arirang Pass (2006), “of course there was a man involved in my foolishness. Much older, glib, colorful and rebellious. A veteran OSS officer [Office of Strategic Services, a US intelligence agency] from World War II and a perennial volunteer for any and all skirmishes.” The older man was Douglas B. Martin (1922-2006) of Long Beach, California, who was serving with the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the Seventh Division in Korea.

In Tokyo Pat Scott met a fellow Portlander, the journalist Taneyoshi Koitabashi, by then editor of the English language newspaper The Nippon Times (which in 1956 would revert its masthead to The Japan Times). Nothing if not brash and headstrong, Scott responded to Koitabashi’s invitation to write for the Times back page by suggesting she provide a column from the frontlines in Korea. She said she had “cut my baby teeth on the front line dispatches of Ernie Pyle and the up front photography of Margaret Bourke-White” [during World War II]. With United Nations Command accreditation and Nippon Times sponsorship, Scott reached Korea. She was outfitted with fatigues and boots and provided with military orders authorising her to use transport and accommodation equivalent to a field grade officer’s privileges. “Carrying only a camera and a typewriter I [caught] a military transport out of the serenity of Japan … and dropped a few hours later into the most profound episode of culture shock of my entire life.” Scott set up base in the Press Billets in Seoul. Over the entrance to the billets bar was a sign saying, “Through these portals crawl some of the best reporters in the world.” Scott suddenly found herself among them. But being the only woman there was deemed unsuitable by other journalists, and Scott was soon transferred to the Fifth Air Force to share accommodation with Red Cross workers and civilian secretaries to air force generals. This had the unexpected benefit of freeing Scott from “formal briefings, sanitised photos and polished status reports”, and she was about the find herself on the frontlines. She sneered at what she termed "crawling reporters" still languishing back in Seoul.

The Press Corps in Seoul weren’t long in realising they had been upstaged by a female greenhorn. Scott’s columns to The Nippon Times had been picked up by the major news agencies and published in the US, to Scott's surprise but the delight of a reading public sick of “sterile status reports”. Pulled into line by James Alward Van Fleet (1892-1992), the four-star general who had replaced General Matthew B. Ridgway as commander of the US Eighth Army and United Nations forces in Korea after General MacArthur’s recall to the US, Scott had nonetheless “touched Van Fleet’s heart” with her reporting. She told US officers she didn't report battles, but wrote about people.

Scott tells this wonderful story about her typewriter in Arirang Pass:

A young Korean girl named

Shin Du Ki cleans our rooms at the billet. She works long hours. We are to pay

her in Korean won which are almost worthless. Like most Americans coming to

this theater, I have heard horror stories about thievery and banditry in Korea.

I’ve been prepped with suspicion, and not just by fellow Americans. Japanese

friends from Hokkaido to Yokohama assure me Koreans are behind every criminal

conspiracy in Japan, from gambling to dope smuggling to murder. Goro Murata,

the business manager for The Nippon Times, bids me farewell with a

warning to keep everything I own under lock and key. No one trusts Koreans.

Adrift in a lawless land,

I take the warnings seriously. My room is padlocked during my frequent

absences. I even padlock it when I shower. But Shin Du Ki has a key. Will

anything be here when I return? My room is always clean and secure when I

return. I begin to relax.

My assets are pathetically

few. A change of fatigues, a pair of boots, a poncho for the monsoon rains, a

camera [Rolleicord], a typewriter, changes of socks and underwear. Nothing

disappears, but my underwear begins to show serious signs of abuse.

I know little about Shin

Du Ki except that her childish enthusiasm and embarrassed little smile bring

warmth to the cold quarters while I am here. Her concern when I leave for the

lines and her exuberant greeting when I return make a cold barracks room feel a

bit like home. I let her take charge of my pathetic possessions, even let her

keep my wallet safe when I go to the lines. Only later will I realize what an

unforgivable temptation that might be.

“Shin Du Ki!” Silence. I

yell again. “Shin Du Ki!” The little Korean girl stands silently in the doorway.

Her feet are braced, her arms are limp at her sides. She stands like a child

about to be slapped. But why? “Who has been in my room? What has happened?” She

continues to brace herself. Tears roll down her cheeks. “Shin Du Ki, was it

you? It’s all right. Just tell me.” She shakes her head, stares at me in disbelief,

still waiting for the punishment. I look through the papers and begin to

understand. Someone has carefully typed copies of my stories and news bulletins

over and over again. I feel like a monster.

“Please, Du Ki, try to

understand. I was tired and frightened. Are you learning to type? It’s all

right. I’ll teach you. It’s okay.” She stares at me, her eyes filled with

tears. Then she runs away. Next day I find a carefully written note: “Dear

Miss: I am very sorry I use typewriter. I never do it again. Each night I go to

school. I study English, typing and piano. In daytime when you go, I use

typewriter. When you ask me, I was afraid and said no. This was lying and I am

sorry. I think you will be angry, but you were not. Your very kind words say

you will teach me typing. Thank you. I want to learn.”

Patricia Corinne Scott was born on Mount Tabor in Portland, Oregon, on July 13, 1929. During the Depression her family moved to near Mount St Helens. Scott graduated from a consolidated high school in Battle Ground and attended the University of Washington. She returned to the US from Korea in February 1953 and married Martin at the Fort Lewis Chapel No 2 outside Tacoma, Washington, on April 11, 1953. The marriage ended in 1968. Patricia Scott Martin later settled in Lacey. She published three other books, Bad Asses and Thieves about the failing system relating to the management of forests, Pay The Piper, about the plight of landlords and tenants during the Vietnam War period, and Blame the Kittens.