The amazing Australian

Polar explorer

Sir Hubert Wilkins

and his love of Underwoods

PLUS: See video footage of a Barr portable typewriter being used as Wilkins’ US Navy submarine Nautilus attempts to travel under pack-ice to the North Pole in 1931

(the typewriter scenes are at the end of this 1min 42sec clip). http://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675042197_Sir-Hubert-Wilkins_engine-room_turning-a-crank_radio-gear_looking-through-periscope

Australian World War I military commander General Sir John Monash once described his fellow countryman Hubert Wilkins as “the bravest man I have ever seen”. Many others thought Wilkins foolhardy in the extreme, especially when he tried to take a US Navy submarine he called the Nautilus under the North Pole in 1931. In terms of typewriter history, however, Wilkins is notable as one of the first men to take typewriters into some of the world’s coldest regions, on explorations to the North Pole and South Pole.

Sir George Hubert Wilkins (1888-1958)

A typewriter had been taken on Sir Robert Falcon Scott’s last, fatal expedition to the South Pole, in 1911-12 (see photos below). But from that latter year, over the next 45 years, Wilkins was to regularly take typewriters with him on his many journeys to both Polar regions.

These images were taken of assistant biologist Ashley George Benet Cherry-Garrard by Herbert George Ponting on the Scott expedition. The top photograph was taken on June 8, 1911. In the second photograph, Cherry-Garrard is working on the South Polar Times on August 30, 1911. Cherry-Garrard's later account of the expedition was called The Worst Journey in the World, at the suggestion of his neighbour, George Bernard Shaw.

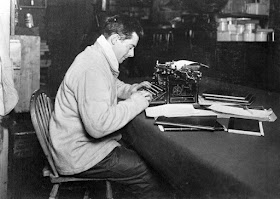

The photograph at the top of this post was taken on board the Nautilus in 1931, and shows Wilkins at an Underwood standard typewriter writing newspaper articles about his adventures.Wilkins was to a large degree funded by William Randolph Hearst on many of his later Polar journeys, on the understanding he would write daily reports for Hearst newspapers.

Packing his typewriter for an Arctic flight

On one of his late 1920s adventures, Wilkins flew over Antarctica in the San Francisco and named the island of Hearst Land after his sponsor. Hearst repaid the compliment by giving Wilkins and his glamorous Australian-born actress wife Suzanne Bennett (below) a flight aboard the Graf Zeppelin as it attempted the first around-the-world flight.

Note the rust on the keytops of the Underwood. Hardly seems surprising!

The Center’s collection of Wilkins typewriters and their cases, as well as this gorgeous Underwood 4 portable typewriter that belonged to Arctic flier Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr (below) can be seen by going to https://byrdpolarmedia.osu.edu/index.cfm?listOfKeyWords=typewriter&fuseaction=search.searchBack

Wilkins bought his Royal portable typewriter from the Jonass Typewriter Service, on Broadway, New York. It appears his Underwoods may have been bought in Sydney, Australia.

George Hubert Wilkins was a famous war correspondent and photographer, newspaper reporter and author, soldier and secret agent, ornithologist and naturalist, geographer and climatologist, aviator and balloonist, submariner and navigator. All this as well as being a pioneering Polar explorer. He was born on October 31, 1888, on a sheep station called Netfield, at Mount Bryan East, 10 miles west of Hallett and 100 miles north of Adelaide in South Australia. He was the youngest of 13 children.

His grandparents were part of the South Australian Company which had settled Glenelg in 1836. His father Henry was the first child born at the Glenelg camp in October 1836.

As a child, Hubert Wilkins experienced the devastation caused by drought and developed an interest in climatic phenomena. He was convinced that the Polar regions were responsible for the gluts and droughts that seemed to happen in climatic cycles within Australia.

In 1903 the family moved to Adelaide and Wilkins studied music at the Elder Conservatorium and engineering part-time at the South Australian School of Mines and Industries. At 18, he was wiring a theatre when he was asked to help a travelling cinema show. He joined the show, thus beginning a lifelong involvement in photography and cinematography.

In 1908, while at the grand opening of the Strand Picture Theatre on Pitt Street in Sydney, he secured a job with the Gaumont Film Company in England. He went back to Adelaide to farewell his family and stowed away on a ship he believed would return him to Sydney. When discovered as a stowaway, however, the ship was already far out in the Southern Ocean, making its way to Algiers. Wilkins agreed to work his passage to North Africa but was dumped in Algiers. Wilkins finally made his way to London. On his way he was kidnapped by Arab gun-running drug-smugglers, to be sold as a slave, but escaped with the help of a girl in the desert tribe.

In England he became the first man to film in flight – first from a balloon and later on the wing of a biplane. With his visits to aerodromes, aircraft naturally became a new interest and through meeting aviation pioneer Claude Grahame-White he soon learnt to fly.

As well as travelling extensively across Europe and North America as a cameraman for Gaumont, Wilkins worked as a reporter for the Daily Chronicle, including covering the 1909 Revolution in Spain and the 1912 Balkan wars between the Turks and Bulgarians. This was the first time moving pictures had ever been taken at the battlefront.

From 1913 to 1916 he was second-in-command on Vilhjalmur Stefansson's Canadian Arctic expedition: Wilkins became adept in the art of survival in Polar regions and conceived a plan to improve weather forecasting by establishing permanent stations at the poles.

He returned to Australia in 1917 to settle his late father’s estate and was commissioned as second lieutenant in the Australian Imperial Force (Australian Flying Corps). Wilkins was awarded the Military Cross for bringing in wounded men during the Third Battle of Ypres at Passchendaele. He later added a bar to it and was promoted to captain. During the battle of the Hindenburg line in late 1918, he organised a group of American soldiers who had lost their officers in an enemy attack and directed operations until support arrived.

One major event Wilkins witnessed was the aerial fight and death of the German air ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen.

In early 1919 Wilkins joined Charles Bean (official Australian war historian, who used a Corona 3 portable typewriter) to revisit Australia's part in the Gallipoli Peninsula campaign. He entered the England-to-Australia air race but his aircraft, a Blackburn he called the Kangaroo, experienced engine failure and crash-landed into a fence at a lunatic asylum in Crete.

In 1920-21 Wilkins made his first visit to the Antarctic, then took part in Sir Ernest Shackleton's Quest expedition of 1921-22 as an ornithologist.

He worked in the Soviet Union in 1922-23 covering the effects of famine, and was then commissioned by the British Museum to return to Australia to collect specimens of the rarer native fauna in the remote northern part of the country. His work was acclaimed by the museum but derided by Australian authorities because of his sympathetic treatment of Aborigines ("In many ways, their state of civilisation is higher than ours") and his criticism of the ongoing environmental damage in the country.

In 1926 he began a program of Arctic exploration by air. Wilkins was in San Francisco in late 1927, preparing to buy an aircraft to fly over the Arctic from Alaska to Spitsbergen, Norway. He had two big Fokkers in storage, which he had previously used in the Arctic Circle, but they were unsuitable for his new purpose. He was able to sell them to two fellow Australians, aviators Charles Kingsford-Smith and Charles Ulm, who re-named one of the three-engine planes the Southern Cross and created the record for crossing the Pacific Ocean from America to Australia.

Wilkins’ own enterprise culminated in his great feat of air navigation: in April 1928, with US Army aviator Carl Ben Eielson as pilot of a Lockheed-Vega, he flew from Point Barrow, Alaska, eastward over the Arctic Sea to Spitsbergen, Norway. The 2500-mile flight took 20 hours and 20 minutes.

Wilkins was created a Knight Bachelor in King George V’s Birthday Honours List in 1928 and awarded the Patron's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. He also became the first recipient of the Samuel Finley Breese Morse Medal of the American Geographical Society.

His book, Flying the Arctic (New York, 1928), publicised the achievement. At the book launch, he met fellow Australian, actress Suzanne Evans (screen name Suzanne Bennett) and married her in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1929.

Wilkins made several more Antarctic journeys between 1928-1930. On the first, while travelling south, his final port of call was in the Falkland Islands. There Wilkins received a secret message from the British Government authorising him to make territorial claims to the Falkland Islands Dependency. This claim ultimately led to the Falklands War in 1982.

In 1931, Wilkins attempted to reach the North Pole by taking a surplus United States Navy submarine, the USS 0.12 (SS-73), renamed the Nautilus, under the pack-ice. Since Wilkins was not a US citizen he was unable to buy the submarine but was permitted to lease it for five years at $1 a year from Lake & Danenhower Inc. The 1930 London Naval Treaty, under which the US pledged to dismantle a range of naval ships and submarines, allowed Wilkins to strike the deal.

However, many serious mishaps and mechanical failures caused the venture to be abandoned, amid ridicule of his ideas. Wilkins was given permission from the US Navy to sink the vessel in a Norwegian fjord in November 1931.

After this adventure, Wilkins was astonished to discover that a distant forefather, Bishop John Wilkins, of Chester, the brother-in-law of Oliver Cromwell, had put forward a proposal in 1648 to take an “Ark for submarine navigations” under the ice to the North Pole.

Wilkins made four further expeditions (1933-34, 1934-35, 1935-36 and 1938-39) to the Antarctic continent, as well as a trip back in 1957 (below, drinking beer with a penguin)).

Because of his age, Wilkins was rejected for service by the British and Australia governments at the outbreak of World War II, but became involved in a number of missions for United States Government agencies, visiting the Middle East, South-East Asia and the Aleutian Islands. From 1942 he was a consultant and geographer with the US Army Quartermaster Corps, which sought his advice on rations and equipment suitable for use in conditions of extreme cold. He served in the US Weather Bureau and the Arctic Institute of North America.

Wilkins died suddenly in his hotel room at Framingham, Massachusetts, on November 30, 1958, a month after his 70th birthday; later his ashes were scattered at the North Pole.

Wilkins Sound, the Wilkins Ice Shelf and the runway on the upper Peterson Glacier, Budd Coast, Wilkes Land in Antarctica are named after him, as are the airport at Jamestown, South Australia, and a road at Adelaide Airport.

Signed: "For Seymour Halpern with best wishes Hubert Wilkins May 12, 1930".

Here is a Corona 3 portable typewriter advertisement in which Norwegian Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen endorses the little folding portable he planned to take to the North Pole.And here is a photo of Geoffrey Lee-Martin, my chief-of-staff on The New Zealand Herald in Auckland, typing a story on an Empire Aristocrat portable typewriter at Cape Royds, which forms the west extremity of Ross Island, facing on McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, in January 1956, when Lee-Martin was covering Sir Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Among Frank Hurley's remarkable photographs of Shackelton's disastrous 1914 Antarctic expedition, at least two plates show a Yost typewriter aboard Endurance. Presumably, the Yost is still at the bottom of the Weddell Sea.

ReplyDeleteThis must be the most dramatic entry in your blog yet. Wilkins is quite a character. Typewriters + adventure: a natural combination!

ReplyDeleteRichard, thank you so much for this most hoped-for response. Yes, Wilkins must have a quite remarkable man.

ReplyDelete