Kathleen McKenna. centre, was “a key force behind the Irish Bulletin”.

Perhaps carried away by their success in finding the offices of the Bulletin - it had had to move 14 times in two years to elude British detection – the Brits blundered in trying to muzzle a publication which was determined to tell Irish people the truth about republican military and political successes, and British excesses. Its first editor, Desmond FitzGerald (left), and later Erskine Childers, were both scrupulous about avoiding fabricated stories on the basis that these would undermine the credibility of the Bulletin’s verifiably true reports. The Bulletin

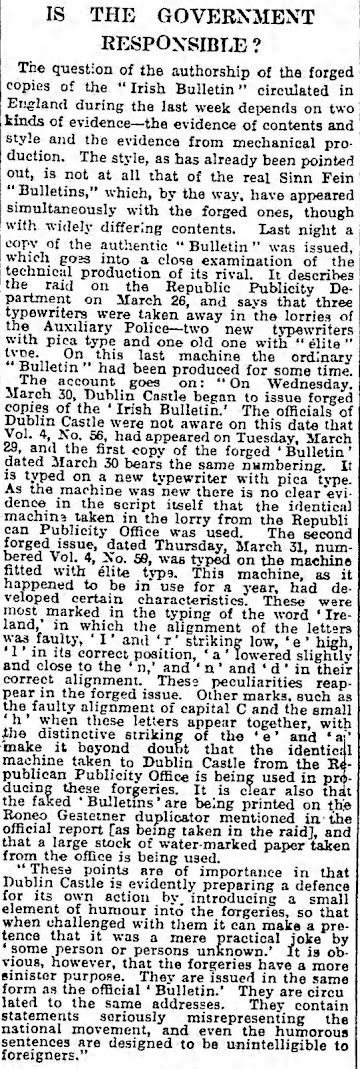

The authors of the counterfeit Bulletin were Hugh Pollard and William Darling. Major Hugh Bertie Campbell Pollard was a British intelligence officer operating out of Dublin Castle as press officer of the Information Section of the Royal Irish Constabulary. Pollard followed up the fiasco of his stupidly forged Bulletin with a bizarre attempt to fake a military engagement in County Kerry (reported as the “Battle of Tralee”). William Young Darling was later knighted as the Unionist MP for the Edinburgh South constituency

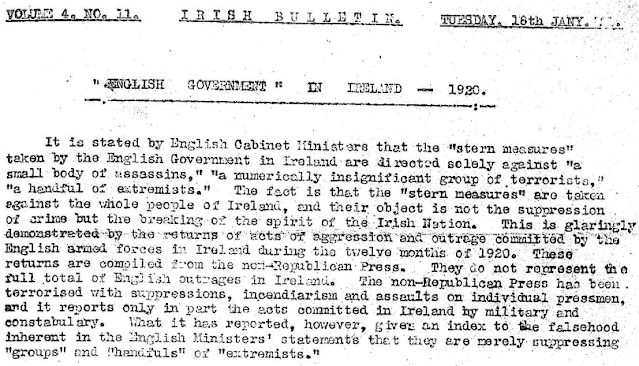

The Irish Bulletin was a counter-propaganda publication, the official gazette of the breakaway, underground government of the Irish Republic (Dáil Éireann), which had been formed on January 21, 1919, following Sinn Féin’s landslide win in general election a month earlier, and which had declared Irish independence. The Bulletin appeared in weekly editions from November 11, 1919, to July 11, 1921. British-enforced censorship had remained in place during the war, meaning Sinn Féin successes and such pleasantries as summary executions by British forces went unreported by newspapers in Ireland and beyond.

Frank Gallagher

At a Sinn Féin Cabinet meeting on November 7, 1919, there was agreement that there should be “A scheme for a daily news bulletin to foreign correspondents, weekly lists of atrocities; entertainment of friendly journalists approved, and £500 voted for expenses …” Four days later the Bulletin made its début. Five issues were issued each week for the next two years, in the face of strenuous efforts by the British to suppress it. In its early days, the paper was produced mainly by Frank David Gallagher and Robert Brennan (left). Brennan, as Sinn Féin's director of publicity since April 1918, had played a leading role in his party's success in the 1918 general election. Gallagher had been London correspondent of William O'Brien's Cork Free Press, closed in 1916 upon the appointment of Lord Decies as Chief Press Censor for Ireland. Gallagher had accused British authorities of lying about the conditions and situation of republican prisoners in the Frongoch internment camp in Wales. Following the Easter Rising of 1916, Gallagher joined the IRA and fought alongside Éamon de Valera during the War of Independence. Gallagher had long stints in prison due to his IRA involvement and went on many hunger strikes (the shortest lasting three days, the longest 41). He contributed to An Phoblacht, the weekly newspaper of the Republican movement.

Kathleen McKenna

Kathleen McKenna was “a key force behind the Bulletin”. A 2014 article in The Irish Times, “Memoirs of a Revolutionary Secretary, Kathleen McKenna and the Shorthand of History”, said, “McKenna may never have fired a gun in anger but she played a significant role in the War of Independence and in the early years of the Free State.” The piece was referring to Teresa Napoli publishing her mother’s memoir, A Dáil Girl’s Revolutionary Recollections. McKenna was born 1897, in Oldcastle, County Meath, to a strongly nationalist family. Her father was a typing teacher and briefly a newspaperman. In 1919 Kathleen joined Sinn Féin and was given the task of typing and printing the Bulletin. In 1931 she married Captain Vittorio Napoli of the Italian Royal Grenadier Guards, whom she first met while holidaying in Italy in 1927. They lived in Libya and Albania before settling in Rome. She became a regular contributor to the Irish Independent, The Irish Times and other Irish and international newspapers.

McKenna is referring to Arthur Griffith, a writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He served as President of Dáil Éireann for eight months before he died in Dublin of a cerebral haemorrhage in August 1922. Ten days later Michael Collins' was assassinated in County Cork. 'Béannacht de leath a leinbh' is a blessing to a godchild.

The actual Corona folding portable typewriter that Winnie Carney used under fire in the Dublin General Post Office during the 1916 Easter Rising was, miraculously, tracked down by a BBC documentary team in 2016, still in remarkably good shape.

Winnie Carney

Yet the British had shown themselves five days earlier to be capable of far, far worse. Bloody Sunday (November 21, 1920) began with an Irish Republican Army operation, organised by Michael Collins, to assassinate the “Cairo Gang” - a group of undercover British intelligence agents working and living in Dublin. IRA operatives killed or fatally wounded 15 men. Most were British Army officers, one was a Royal Irish Constabulary sergeant, and two were Auxiliaries responding to the attacks. Later that afternoon, British RIC members called “Black and Tans”, Auxiliaries and British soldiers raided a Gaelic football match in Croke Park. Without warning, the police opened fire on the spectators and players, killing or fatally wounding 14 civilians and wounding at least 60 others. Two of those killed were children. A military inquiry concluded the killings were indiscriminate and “excessive”. This events further turned Irish public opinion against the British, with little wonder. The IRA assassination operation severely damaged British intelligence, while the later reprisals increased support for the IRA at home and abroad.

On the eve of another Gaelic sporting event, the 1931 All-Ireland hurling championship final between Kilkenny and Cork, The Irish Press was launched, with Margaret Pearse, mother of 1916 Easter Rising martyrs Padraig and Willie Pearse, pressing the button to start the printing presses. This signalled the start of the successor to the Bulletin, with the Bulletin’s Frank Gallagher editor of the Press. The Fianna Fáil-supporting Press was a national daily newspaper in opposition to the Fine Gael-supporting Irish Independent and the pro-British Irish Times. It was founded by a War of Independence political leader, New York City-born Éamon de Valera, “To give the truth in the news …” Financing had been raised in the United States during the War of Independence by a bond drive for the Dáil. De Valera went on to serve several terms as head of government and head of state.

He was still alive when I joined The Irish Press almost

50 years ago, with his son Major Vivion de Valera as managing director. IRA

historian Tim Pat Coogan, the son of an IRA volunteer in the War of

Independence, was my editor.

I had previously worked for the Cork Examiner (now Irish Examiner), where among my predecessors was Tadgh Barry, another victim of the British during the War of Independence. Barry was on active service during the 1916 Easter Rising and was selected as a Cork delegate to the historic October Sinn Féin convention in the Mansion House. Barry was arrested by British authorities on the ground he had delivered a "seditious speech" and was imprisoned. He was arrested again in 1918, charged with being a conspirator in the so-called German Plot, which British authorities alleged was a plan by members of Sinn Féin to collude with the German Empire to bring firearms to Ireland. In 1920, Barry was elected to the position of alderman in Cork, placing him in a position of power alongside the Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain and newly elected MP Terence MacSwiney. Mac Curtain, an officer in the Irish Republican Army, was killed in front of his wife and children in an assassination by members of the Royal Irish Constabulary. MacSwiney succeeded Mac Curtain as Lord Mayor, only to die in October following a hunger striker. Soon after the city was devastated by the Burning of Cork in December, when members of the Black and Tans torched the city in an act of arson born out of anger from loses to the IRA. In the wake of MacSwiney's death, Barry and eight other councillors were arrested. Barry was transported to Ballykinlar internment camp in County Down, where he was placed with 2000 other arrested Irish Nationalists. On November 15, 1921, Barry was conversing with fellow inmates at the edge of the camp when he was shot dead by a young sentry guard.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I do not accept anonymous comments.

I only allow comments under User IDs provided I know who that person is.

Do not ask me to evaluate typewriters.

Comments must be relevant to the post.

As the author of these posts, I make the decisions about what they contain - it is not open to discussion.