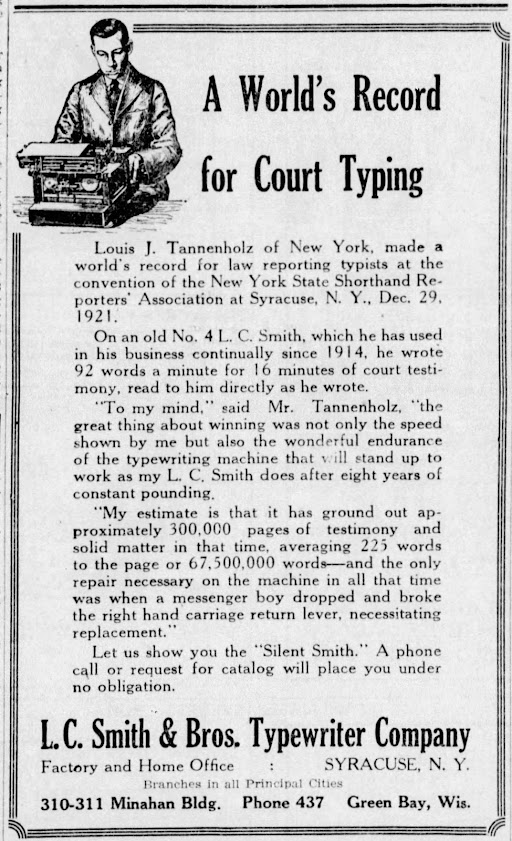

A century ago, major US typewriter manufacturers were in the habit of sending “good news stories” to their agents around the world. These articles were positive publicity puff pieces, penned by PR people about the manufacturer’s machine, and were often passed on to the agent’s local newspaper, which printed them virtually unchanged (the one addition being the name and trading address of the agent). As far as the newspapers were concerned, it was interesting, read-worthy and free “filler” copy – and the deal usually included a large, paid advertisement with an engraving. Sound business practice for all concerned.

One classic example in 1922 concerned a New York law reporter called Louis Jerome Tannenholz, who had used a regular stock L.C. Smith No 4 standard typewriter to type 67½ million words over eight years. Tattenholz, born at East 107th Street, Manhattan, on St Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1888, started work as an insurance broker but in 1913 became a law reporter based at 150 Nassau Street, close to New York City Hall and the New York County Supreme Court. The next year he acquired his trusty L.C. Smith No 4, which had reached the market in 1911.

Tannenholz’s great

typewriter feat was actually achieved at the 46th convention of the New York

State Shorthand Reporters’ Association at the Court House in Syracuse (Syracuse also being the

home of the L.C. Smith & Brothers Typewriter Company) on Thursday, December

29, 1921. By the following morning, the New York Daily News had caught

up with Tannenholz and had interviewed him and photographed him at his “old” L.C.

Smith. The company’s public relations department went into overdrive and from

March until August the story of his typing achievements appeared from Ohio to

Hawaii.

At the shorthand reporters’ convention in Syracuse, Tannenholz set a world record for law reporting typists by typing at a rate of 92 words a minute for 16 minutes (1472 words). He typed court testimony, read to him by a court stenographer, on seven testimony-sized pages. The dictation was in question and answer form, and included part of a judge’s charge to the jury.

Tannenholz said he estimated that since 1914 he

had typed 300,000 pages on the L.C. Smith, averaging 225 words a page, or 67½ million

words all up. In that time, “the only repair necessary on the machine … was

when a messenger boy [not me!] dropped it and broke the right hand carriage

return lever, necessitating [a] replacement.”

Tannenholz was not new to winning typewriter speed championships and setting typing records – previously he had won both amateur and professional titles, from 1914-17 inclusive, “dictaphone style” – that is, typing from dictation using headphones. In Chicago in 1916 he typed 134 words a minute for a new world record in dictaphone transcription. Away from typing tests, he transcribed court reports in famous cases, such as policeman Charles Becker’s murder trial in 1914, the 1917 kidnapping trial of Harry Kendall Thaw and the 1920 trial of five Socialist assemblymen in the New York State Legislature in Albany.

Tannenholz told the Daily News that a secret to his success was the use of talcum powder on his fingers to stop them from becoming sticky. He kept a box of the powder beside his typewriter and regularly dipped his fingers into it. “I indulge in no finger exercises, but take great care of my hands, soaking them in hot water preparatory to engaging in any work requiring speed. My typewriter keys are supported by inside springs, giving a lightness and deftness of touch that greatly increase my speed.” He used only two fingers on each hand. “Speed on the typewriter can be obtained only by assiduous application – constant practice with the one goal in view. However, I have not made a practical study of it.”

While the Daily News reporter held a stopwatch, Tannenholz demonstrated his skill by typing 184 words of familiar matter in one minute, using 660 strokes, 11 movements a second. Later, Tannenholz was quoted by Typewriter Topics as saying, “I think I have done far better in my routine work than the record made in Syracuse.” On his first visit to the L.C. Smith plant, Tannenholz gave an exhibition in which he typed at 185 words a minute with familiar matter.

Tannenholz was back in the

news in 1928 when he joined the huge party aboard the 11 cars on New York Governor

Al Green’s special train during Smith’s Presidential election campaign in

September-October 1928. Tannenholz was one of two typists travelling with Smith’s

group. The cars included a Club Pullman car in which the governor held daily

press conferences (it was equipped with a barber shop and shower room), a

especially equipped office car for correspondents with typewriters, three

Pullman compartment cars for the Press and a work car equipped with mimeograph

machines and typewriters. The campaign train went from New York to Chicago,

Omaha, Oklahoma City, Wichita, Dodge City, Colorado Springs, Denver, Cheyenne,

Billings, Butte, Bozeman, Fargo, Minneapolis and back, with a myriad of other

stops along the way.

In spite of the enormous cost of the campaign train, Smith, the Democratic candidate and the first Roman Catholic to be nominated for President by a major party, was crushed by a former Kalgoorlie (Western Australia) goldmine engineer, Herbert Hoover, who won 444 electoral votes to Smith’s 87. Hoover won 40 states to Smith’s eight (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, just, Mississippi, Rhode Island, just, and South Carolina).

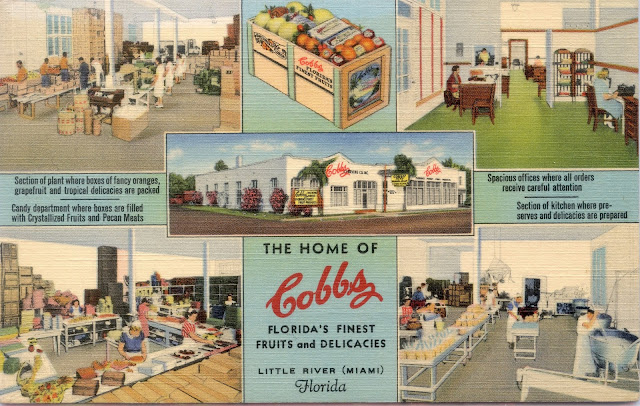

Soon after the US joined World War I, Lou Tannenholz and his wife Rose changed their surname from the Germanic to the Anglican Tanner. Lou Tanner retired from law reporting in 1941 and moved to Florida, where for more than 20 years he was general manager of Cobb’s fruit stores. Lou died in Miami on January 22, 1963, a month short of his 75th birthday.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I do not accept anonymous comments.

I only allow comments under User IDs provided I know who that person is.

Do not ask me to evaluate typewriters.

Comments must be relevant to the post.

As the author of these posts, I make the decisions about what they contain - it is not open to discussion.