For we Australians, the Dangerous Summer quite possibly still lies ahead. Things have been bad enough as it is. And Covid-19 isolation is all the more excruciating when one is cooped up without a decent magazine to read. We subscribe to The New Yorker and Britain’s Literary Review. Subscriptions work out a lot less expensive than waiting to buy copies at the newsagent’s, and by rights magazines such as these should arrive by mail two to three weeks ahead of them reaching the stands. But rights went out the window when Australia Post laid off staff and, with the pandemic, parcels started to pile up. One estimate has 2½ million items still waiting to be delivered.

Our mags are now starting to slowly trickle in. But earlier this month, in

desperation, I went back to my extensive magazine stockpile, and dragged out a

copy of LIFE from precisely 60 years

ago. It was the issue of September 5, 1960, with a smiling Ernest Hemingway on

the cover and the first instalment of Hemingway’s bullfighting epic The Dangerous Summer inside.

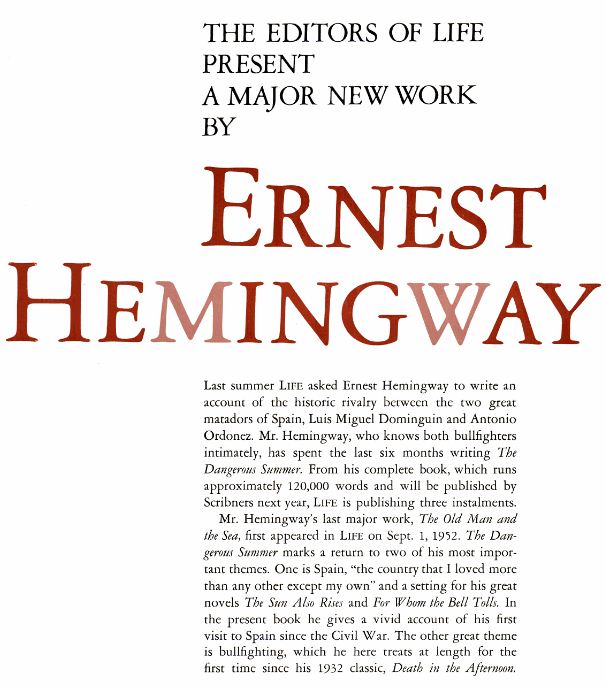

LIFE said “we’re all lucky – we’re welcoming an old friend and contributor

back … It has been eight years since Hemingway produced a major work [The Old Man and the Sea, which won him

the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954. This had appeared in LIFE on September 1, 1952, and two

million copies of the magazine sold in two days].” LIFE

commissioned The Dangerous Summer in

the middle of 1959 (on September 7, 1959, it published a 10-page picture spread

from Larry Burrows and James Burke of mano

a mano fights Hemingway covered.) Hemingway left Cuba for Spain via New

York on July 25, 1959, and returned to New York at the end of October. LIFE originally asked for 5000 words

and promised payment of $30,000 ($53.60 a word in today’s money). But Hemingway

produced 108,746 words on 688 typed pages. His friends A.E. Hotchner and LIFE’s Paris bureau chief William J.

Lang helped Hemingway trim down the piece and by March they had

pruned it to 63,562 words. LIFE published

35,000 words in three instalments. Even then, one Virginian reader described The Dangerous Summer as “elephantine

pirouetting”, “self-conscious cuteness” and a “blizzard of tortured verbiage”.

Other

than the 24 pages LIFE devoted to Hemingway, the September 5, 1960, issue

covered many other interesting topics: letters about votes for women, a

full-page tribute to the great songwriter Oscar Hammerstein II, who had died in

August 23, a colour ad for a Smith-Corona Galaxie portable typewriter, Sirimavo

Bandaranaike becoming the prime minister of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and thus

the world’s first female prime minister (she eventually served three terms over

40 years), Princess Ira von Fürstenberg and her marriage at age 15 to Prince

Alfonso of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (he was

31) and her relationship with Francisco “Baby” Pignatari, a Brazilian industrialist

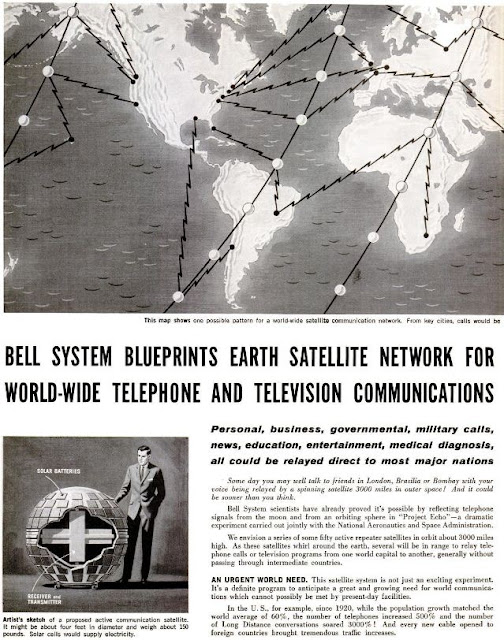

eight years older than Alfonso, and a couple of creepy young TV extras. I was also intrigued by the double page ad

for a Bell System earth satellite network.

My

favourite item, however, was this one about the guy who jumped the fence before

the Opening Ceremony at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome and ran 200 metres to

the finish line. I’d done much the same thing before the opening of the 1988

Seoul Olympic Games, except in my case the stands were still empty and I didn’t

manage a 200m sprint, just a gentle jog to the line.