Total Pageviews

Wednesday, 19 October 2022

Wednesday, 12 October 2022

Vale Angela Lansbury (1925-2022)

Tuesday, 20 September 2022

Mitterhofer Typewriter Claim Upsets US Historian

Sunday, 18 September 2022

The Queen is Dead, Long Live the King’s Typewriter

Charles got his typewriter on May 5, 1949, nine days before he turned six months old. It was given to his mother, then Princess Elizabeth, at the British Industries Fair at Olympia in London. The typewriter is an Empire Aristocrat with 18-carat gold key rings and typebars (which Gary’s doesn’t have). The Aristocrat was presented to the future Queen by a Mrs S.S. Elliott, secretary of the Office Appliances Trade Association. Future British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, as president of the Board of Trade, had welcomed the princess, her husband, mother and sister to the fair.

Mrs Elliott told Elizabeth, “We thought that perhaps Prince Charles

might begin to learn his alphabet from the keyboard.” “What a good idea,” replied Elizabeth.

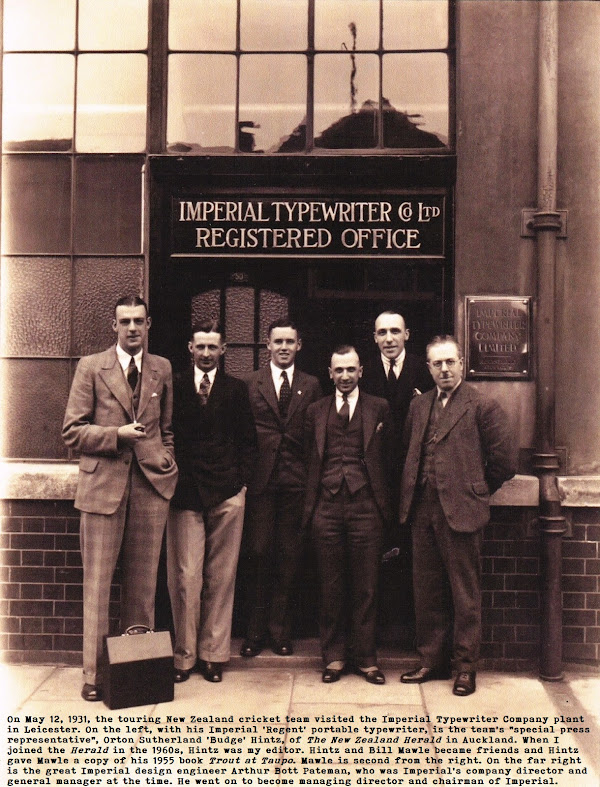

The Empire Aristocrat was made by Bill Mawle’s company, British Typewriters, in West Bromwich. It was from this plant, originally established as George Salter’s Spring Works, that in 1878 the West Bromwich Albion football club emerged, out of the company’s cricket team. In 1935 Mawle, a World War I flying ace (and later Group Captain Mawle OBE DFC), was sales manager for the Imperial Typewriter Company in Leicester. He was sent to a trade show in Switzerland and there spotted a new slimline portable typewriter, later to become famous as the Hermes Baby. Mawle bought the British rights to the design for £3000 and returned to Britain to begin manufacturing at the then abandoned Sattler factory. Mawle’s company, later known as Empire Typewriters, was sold to the American typewriter concern L.C. Smith Corona in 1962.

WD-40 and Typewriters: Never the Twain Should Meet

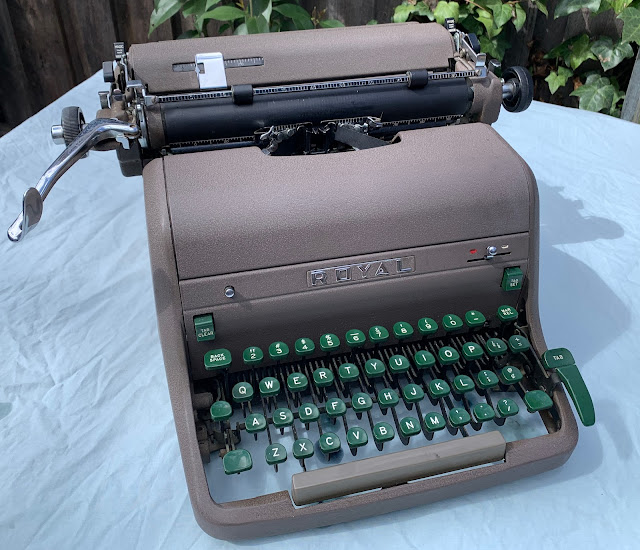

Whenever I fix a typewriter, I offer the customer free after-service care. Yesterday, for the first time, that offer was taken up. Three years ago I had worked on a 70-year-old Royal HHP standard which had been bought for a Canberra woman by her mother-in-law, from the San Francisco Typewriter Exchange. Last week the owner contacted me to say the keys and typebars wouldn’t move. She wasn’t wrong. It would have taken a sledgehammer to get them operational.

The owner said she had no knowledge of anyone spraying

anything into the segment. But, from experience, that is exactly what had

happened. And the guilty item: WD-40! WD-40 is a water dispersant spray, not a

lubricant. WD-40 shouldn’t be allowed within a 100 miles of a typewriter, the keys

and typebars of which work through a combination of a multitude of gears, levers and

springs and good ol’ gravity. Allow WD-40 anywhere near those gears, lever connections

and springs, or the groves of the segment, and you’re asking for big, big

problems. WD-40 works like Lanolin, it congeals and clogs.

It took 24 hours of serious bubble bathing, relubricating and much

gentle manual persuasion to get the keys and typebars working properly again. Today’s

lesson? Never use WD-40 as a lubricant. And never, ever, use it on a typewriter.

Saturday, 13 August 2022

When Jeff Missed Out To The Typewriter Guy

While I was cleaning up this Remington Noiseless portable for today’s typewriter presentation, I came across what I at first took to be a bit of foliage or piece of cloth buried inside the workings of the machine. Nothing unusual in that. I brushed it out and only some time later looked more closely at it - and realised it was a typed slip of paper. “Do you love me or Jeff” was the plaintive cry of the guy who once owned this lovely machine. “No” the future Mrs Typewriter Guy seems to have written on it in pencil. I’m taking it to mean she didn’t love Jeff, just the Typewriter Guy. Lovers of typewriters, after all, make the best lovers. What’s your interpretation?

Monday, 11 July 2022

Friday, 8 July 2022

RIP James Caan (1940-2022)

Actor James Caan, who died in Los Angeles on Wednesday, aged 82, will be best remembered by typewriter lovers for his manhandling of a Royal 10 standard in the 1990 movie Misery. He also used a Smith-Corona electric portable in that film, and it wasn't the only movie in which Caan used a typewriter. He was seen typing on an L.C. Smith in 1975's Funny Girl, in which he played impresario and theatrical showman Billy Rose, opposite Barbra Streisand as comedienne Fanny Brice, Rose's first wife, and also in Neil Simon's semi-autobographical Chapter Two in 1979, in which Caan played George Schneider, a New York City author. In this movie Caan was also using a Royal, but a much more modern Ultronic electric. James Edmund Caan was born in The Bronx on March 26, 1940.

Saturday, 2 July 2022

Typewriter Dinkuses

Did you know dinkuses, the plural of dinkus, is an anagram of unkissed? Yet there once was many a time when, rushing against deadline to make up a sports page on an evening newspaper’s stone floor, that I kissed the wooden back side of a dinkus, offered to me by a compositor as a way of filling a gaping hole, left by a story which had fallen an inch or so short. In more recent times, I have gathered a small collection of typewriter-related dinkuses, as has Peter Weill (see ETCetera No 109, Summer 2015).

In the meantime, we can always use the scan of a typewriter dinkus when we need one.

Seven years ago, Writing New South Wales tweeted that “dinkus” was a “new word from today”. It was at least 90 years behind the times, possibly as much as 140 years and maybe even 160 years. My own efforts to find the origin of the word dinkus, as I know it, relied in March 2011 on Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary, which said: “A dinkus is a small drawing used in printing to decorate a page, or to break up a block of type. It was coined by an artist on [Sydney’s] The Bulletin magazine in the 1920s, and it is derived from the word dinky, meaning ‘small’.” I now find that in 1952, the Melbourne Herald's head proof reader, Charles Crampton, said there was a printers' embossing tool called a "dinkus-and-die", with a "dinking" tool which fitted perfectly into the die. "Hence we get a 'dinky-die fit'." So from dinkus came the Australian term "dinkie-die", meaning straight and true ("It's not a lie, it's dinkie-die"), as well as the expression "fair dinkum" ("Fair dinkum, I use a typewriter all the time"). The Herald journalist, social commentator and activist E.W.Tipping said, "Printers call a small picture used to fill up a space in the compositor's forme a dinkus, the latter getting its name obviously from it being used to wedge tightly the type."

Wiktionary gets it right by describing dinkus

as “A small drawing or artwork used for decoration in a magazine or periodical”.

In print newspapers in the hot metal days, a dinkus was usually used to give the eyes a

momentary rest from reading a page of “grey matter” – that is, columns of a small

black typeface on a light background. Wikipedia gets it wrong by confining dinkus

to “a typographic symbol which often consists of three spaced asterisks in a

horizontal row … The symbol has a variety of uses, and it usually denotes an

intentional omission or a logical ‘break’ of varying degree in a written work.”

Wikipedia compounds its mistake by adding, “In Australian English, particularly

in the news media, the word refers to a small photograph of the author of a

news article. Outside of Australia, this is often referred to as a headshot.”

Wiki is most decidedly wrong on this count.

Last month (June), The New Yorker featured typewriter

use in dinkuses (it calls them “spots”), one (seen at the top of this post) above a wonderful tribute to the late Roger

Angell (“That Titian of the Typewriter”), written by the incomparable David

Remnick, the other among the regular “spots” that run through the magazine, in

this case showing people writing using all manner of machines and methods.

This last one was not entirely "new", as a similar idea had been used to advertise the Bar-Let portable typewriter in 1934:

Tuesday, 28 June 2022

Vale Frank Moorhouse (1938-2022)

Frank Moorhouse, one of Australia’s most celebrated and

controversial writers, died early on Sunday morning at a hospital in Sydney, aged

83. Moorhouse wrote 18 books, many screenplays and countless essays. He was renowned

for his use of the discontinuous narrative in works such as The Americans,

Baby and Forty-Seventeen. He was a life-long activist who

supported feminism, advocated for gay liberation and supported indigenous land

rights. Moorhouse’s activism on behalf of authors led to him becoming a member of

the distinguished writers panel for PEN, an international organisation for

freedom of speech for poets, essayists and novelists. The 1989-2011 “Edith

Trilogy”, a fictional account of the League of Nations and made up of the novels

Grand Days, Dark Palace (which won him the 2001 Miles Franklin

Literary Award) and Cold Light, affected the career paths of many

women.

Moorhouse was born in the New South Wales town of Nowra a few days before Christmas 1938. His New Zealand-born father, electrical engineer, dairy machine inventor and manufacturer Frank Osborne Moorhouse, moved to Australia in 1925. The younger Frank began his working life in 1955 as a cadet reporter on Sydney’s Daily Telegraph and from 1957 worked as a journalist for the Wagga Wagga Advertiser, Riverina Express, Lockhart Review and Boorowa News. At 18 he published his first short story, “The Young Girl and the American Sailor”, in Southerly magazine. Moorhouse lived for many years in the Sydney suburb of Balmain, where together with Clive James, Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes he became part of the “Sydney Push” - an anti-censorship movement that protested against right-wing politics and championed freedom of speech and sexual liberation.