To Mark

International Women’s Day

(This was

part of Google's IWD Doodle video)

The superstars of speed typewriting are high among my favourite blog subjects, as long-time followers of ozTypewriter will well know. And there can be no more pleasing feedback for the long, lonely hours that go into researching and writing these posts than to hear from the families of people once so prominent in typewriter history. For example, in the past two years I’ve received comments from the great George Hossfeld’s grand-daughter Brooke, Parker Woodson’s great-great-grand-daughter-in-law Cat Woodson, and the immortal Margaret Owen’s son Owen ‘Bud’ Tyler. Maybe this post will find more family members of the champion typists.

Or answer the question: Whatever became of Hortense Sandé

Stollnitz-Rogers?

STOLLNITZ

& The GILBRETH LAB

Florian Hoof in Angels of Efficiency: A Media History of Consulting (Oxford University Press, 2020) says that in 1916 corporate consultants Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were commissioned by the Remington Typewriter Company to carry out studies involving Remington’s newly introduced typewriter, the Standard 10. “ … the firm competed at the time against the Underwood No 5 model … In this competition between the two companies, heavily promoted, nationwide typewriting contests played a major role. Here, however, Remington was regularly beaten by Underwood. This was the context for Gilbreth being tasked … of using his film-based method to train a group of typists the 10-finger system on the new machine (Ed: The 10-finger system had been around a very long time before all this happened.) Underwood’s supremacy in the typewriting contests had to be broken. The goal of the [Remington] commission was less to develop structural forms of motion rationalisation, and more to increase the typing speed of a few individuals whose high-level performances were effective for publicity purposes. These performances were subsequently to be used in advertisements as an argument for the superiority of Remington’s typewriters.”

Hoof points out that Hortense Stollnitz, the typist employed by Remington and used by the Gilbreths in their study (see images left), “achieved the highest number of keystrokes in the field of contestants, she had by far the highest error rate … [Underwood] typists may well have typed more slowly, but their error rate was up to 10 times less. This was a sign that, although the Gilbreths were capable of generating euphoria and motivation among their typists, their actual training method left a lot to be desired. The promotional coup of a victory in the amateur class demanded by [Remington] was reached, but Gilbreth lacked any long-term viability. Nonetheless, the studies for the consultancy firm Gilbreth Inc represented a major publicity success. [Gilbreth] relied on the chronocylegraph footage, photographs and film produced there, which showed the immaculate superiority of lab-based consulting. This impression became more widespread through the notices posted by Remington, such as through American newsreels, which screened some of this film footage.”

In Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: A Fragmented

History of Typewriting (2005), the author quotes Gilbreth as claiming “he had

helped Remington develop the world’s fastest typist”. The typist in question

was Hortense Stollnitz, who in 1917 was to achieve what was regarded well into

the mid-20th Century as the greatest average number of words typed per minute

in one hour: 159.1. Stollnitz worked with the Gilbreths in their laboratory,

closely beside her arch Underwood rival Margaret Owen. Although they were

employed by companies locked in fierce and

costly competition, Stollnitz and Owen nonetheless became close friends, largely

through attending various promotional events together.

THE WORLD

CUP OF TYPING

In 1906, nine of America’s leading typewriter manufactures were persuaded by George Henry Patterson, Ottawa-born founder of Chicago-based Office Appliances magazine, to chip in some money for what was called “The Thousand Dollar Silver Trophy”, to be awarded annually for “typewriter speed and accuracy”- or, more accurately, to go to “the fastest typist on Planet Earth”, as Underwood would have it. The 36-inch high, 21½-inch wide cup was made by Watson & Newell at 67 Mechanic Street in Attleborough, Massachusetts, listed last year on the National Register of Historic Places. It was engraved on its top lip, “World’s Trophy: Typewriter”.

From 1906 until 1923, Remington did continue to try to compete with the Underwood 5. And when, in 1916, it introduced the “Self-Starting Remington”, it began to believe it was finally in with a decent chance, the more so because Remington had as the self-starter’s prime user one Hortense Sandé Stollnitz, the 18-year-old Los Angeles-born daughter of a Polish rabbi and author. Stollnitz was definitely a world champion in the making. “Heretofore typewriter speed has been blocked by machine limitation,” said Remington’s advertising for the “self-starter”. “ … a simple invention gives an automatic speed gain of 15 to 25 per cent.” Trouble is, Remington never really explained in full quite how this gain could be achieved. Nor did “self-starting” overcome Stollnitz’s one big, enduring handicap: she could type like the wind, but she made far too many errors. Nonetheless, Remington’s advertisements of the achievements of its own speed typing team started to match that of Underwood, which had been paying for massive newspaper advertising space to publicise world championships results since Rose Fritz’s win in 1906.

Fritz’s win at Madison Square Garden in New York City is listed as the first in “official” world championship events. Of course there had been “world championship” typing competitions since 1888, when Frank McGurrin, using a Remington, beat Louis Traub (Caligraph) in Cincinnati, and was then beaten the next month by Remington’s official representative, Mae E. Orr, in Toronto. But with the emergence of the Underwood 5 in 1901, the Underwood company seized on a promotional opportunity to establish the model 5’s credentials by forming a professional speed typing team under the coaching of Charles Vonley Oden and Charles E. Smith.

Fritz was the first champion to emerge from that Underwood team

of full-time speed typists, and had claimed a “world championship” seven months

before James Nelson Kimball’s series of “official” world championships began with

the October 30, 1906, event during National Business Show in Madison Square

Garden. Fritz was the favourite in a “championship contest” in New York on November

2, 1905, and had won at the National Business Show in Chicago on March 22,

1906, beating then Remington operator Emil Trefzger. Her performance inspired

Patterson to find the funding for a properly organised world championship, and for

an appropriate trophy to go with it. Patterson died, aged just 37, in Richmond,

Indiana, on March 28, 1908, but he had lived long enough to not only see his dream

of a world championship come to fruition, but in short time to take very solid

root.

Heading into the October 1906 event, organised

by the Madison Square Garden’s management team of Cochrane & Payne, US newspapers

reported that Fritz would be “defending” her title in New York. And the first world

championship event did indeed have an actual international flavour, for among entrants

were Martha Baumgarten from Berlin, Elizabeth Mason from London and a Frenchwoman,

Eloise Dupont.

REMINGTON

SET EARLY PACE

The term “world champion speed typist” did get bandied about a lot in the three years before Kimball stepped into Patterson’s shoes and organised the 1906 New York event – doing so, presumably, to give the “world champion” title some form of broadly accepted recognition. Still competing at age 39 in 1905 was Frank McGurrin’s brother Charles, who in a January 1904 Collier’s ad for the Fay-Sholes was declared “speed champion of the world”. But the winner of the November 2, 1905, New York championship was a surprise to officials and spectators alike – they’d been keeping their eyes on Fritz (just 17 and three weeks old) and Mae Carrington of Springfield, Massachusetts. Way off in one corner Paul Munter was quietly plugging away on a Remington and to everyone’s surprise finished up beating Fritz with 69.96 wpm to 69.46. Carrington was third on 66.8. In those days the competitions were held over 30 minutes, but from October 1906, under Kimball’s rules, the world championship was decided over an hour’s typing.

Munter, right, a member of a noted family of judges, attorneys and lawyers, was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on August 19, 1880, and raised in Spokane, Washington. He graduated from Gonzaga College there and then studied law at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He became a Supreme Court reporter and died in Brooklyn on February 27, 1950. Based on the way things were judged by newspapers until Kimball took control, Munter was the “world champion” before Fritz. What’s more, by using a Remington, he had picked up that company’s leadership in speed typing from where Frank McGurrin and Mae E. Orr had left off in the late 1880s. Perhaps spurred on by Munter’s win over Fritz, Underwood lifted its team coaching efforts in 1906 and was never again beaten by Remington in a major championship. Fritz’s speed improved markedly over the 12 months from her defeat to Munter, and she won the first “official” world championship with 81.75 wpm, a 12.29 wpm improvement on her 1905 effort. Munter wasn’t even the highest of the Remington typists in the 1906 championship, finishing fifth with just 60 wpm. He had typed 5122 words in an hour, to actually lead Fritz by 12 words, but Kimball had introduced deductions for errors, a five-point penalty (Munter had a massive 413 errors and 2065 penalties to Fritz’s 41 errors and 205 penalties). In the end Fritz won comfortably from Underwood teammates Otis Blaisdell (64 wpm) and Boston’s Lillian V. Bruorton (62 wpm). Remington filled the last three places.

UNDERWOOD

GOES HEAD HUNTING

Paul Munter immediately switched to Underwood and his typing mistakes decreased considerably at the 1907 world championship, but he was still fifth on 60 wpm behind Fritz (87), Blaisdell (83) and the new Remington hope, Emil Trefzger (78), from Peoria, Illinois. May Mathews, another member of the Underwood team, was fourth (69). Overkeen to make the point about its machine’s superiority, Underwood’s advert placed Bruorton sixth, when in fact she’d finished 13th, behind six Remington competitors!

Remington came as close as it ever had (until 1917) to winning

the “official” world title in 1908, when Trefzger finished second behind Fritz by

a mere 0.92 wpm - 87.38 wpm to 86.46. Trefzger

pushed Blaisdell to third (80). Seven of the placed eight were Underwood users.

Underwood blamed the close finish on the organisers: “Both Miss Fritz and Mr

Blaisdell were seriously inconvenienced and handicapped by their positions

being in a dark corner, and also forbidden to use the electric drop lights

provided for them. The table used by Miss Fritz was also unevenly placed on the

floor, which necessitated moving her chair to follow the table. Both Miss Fritz

and Mr Blaisdell were unfortunate in having their typewriting sheets fall to

the floor, losing valuable time, as well as losing their place on the

manuscript.”

Notwithstanding all the excuses for Trefzger getting so close to Fritz, and ahead of Blaisdell, Underwood quickly set about luring Trefzger away from Remington’s employment, and he switched camps to join the Underwood team. Underwood had been doing this sort of thing since the model 5 first came out in 1901 – at a time when it did not have a speed typing team and Remington did. So Underwood simply stole talented speed typists from Remington. Alice Schreiner (left) and Carrington changed allegiance from Remington in time for them the demonstrate the new Underwood 5 at the Buffalo World’s Fair. In 1908 an amateur division was added to the world championships, and a novice division in 1909. The brands Smith Premier, Monarch and Remington occasionally bobbed up in the lower classes, allowing Underwood to spot and snap up any emerging talent if it wanted to further strengthen its full-time team.

In Trefzger’s case, as an enticement, Underwood sent him on a

trip to Europe in 1909, and in his absence Fritz was unchallenged to take out

her fourth straight “official” world title. She scored a new record 95 wpm to

beat Blaisdell (92) and two long-serving Canadian Underwood typists, Leslie

Coombes (84) and Fred Jarrett. In 1910, with Fritz touring extensively on behalf

of Underwood and Trefzger back in Europe, Blaisdell won the world championship with

109 wpm, beating Florence Wilson (95.3), J.L. Hoyt (94.9) and Coombes (93.1). Blaisdell

proved his superiority over both Fritz and Trefzger by retaining the title in

1911 and extending his record to 112 wpm. Wilson was second (110) and Fritz and

Trefzger equal third (107).

Trefzger was second and Blaisdell third behind Wilson in 1912 - Wilson setting a new record of 117 wpm to edge out Trefzger on 116, Blaisdell on 115, Margaret Owen on 114 and Fritz on 113, all breaking Blaisdell’s previous record. Trefzger’s brother Gus was sixth on 111, followed by Hoyt on 110, Bessie Linsitz on 109 and Bessie Friedman (right) on 104. It was by far the tightest competition in the event’s history. Significantly, there were only two Remingtons (13th and 15th) and an L.C. Smith (10th) among the 15 finishers.

In the absence of Wilson, the sublime Owen won the first of

her four titles in 1913, at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, pushing

the record out to 125 wpm to beat the two Trefzger brothers, Emil on 120 and

Gus on 117. Emil Trefzger, once Remington’s Great White Hope, won his one world

title in 1914, making it nine-in-a-row for Underwood and taking the speed record

out to 129 wpm. With Trefzger and Blaisdell on Underwood duties at the

Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, Owen regained the world title with a new world

of 132 wpm, beating Gus Trefzger (124), Fritz (123) and Friedman (122).

Margaret Owen in the Gilbreth studios.

STOLLNITZ

ARRIVES ON THE SCENE

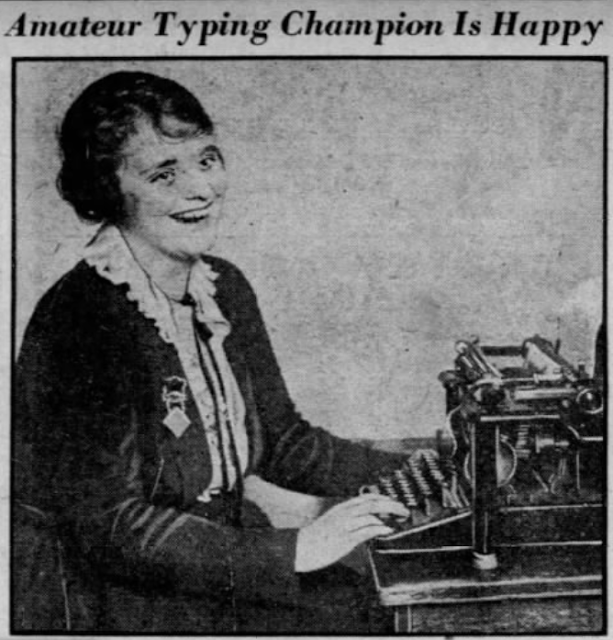

For Remington, the exciting news from the October 25, 1915, championships at the 69th Regiment Armory was not so much that Parker Claire Woodson came third behind future Underwood world champion William F. Oswald in the amateur section, but that Hortense Sandé Stollnitz won the novice division on a Remington 10 with 114 wpm over 15 minutes, 16 wpm better than any other novice had previously achieved. The event was open to those who had not used a typewriter before September 1914, and indeed Stollnitz had only been typing since November that year, just before her 17th birthday. She had taken up typing ahead of an intention to enter the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia University, after graduating from Bay Ridge High School in Brooklyn in January 1915, and her typewriter skills were spotted by Remington speed typing team manager Percy L. Waters.

Stollnitz was to prove Remington’s best hope of breaking the Underwood monopoly since Emil Trefzger in 1908. And Stollnitz, unlike Trefzger, would remain loyal to Remington for the rest of her working life. Her progress was remarkable. Within four months of starting her typing, in March 1915 Stollnitz took part in the Eastern States novice competition in Philadelphia and reached 88 wpm, then took out the world title in October. In April 1916 she stepped up to the amateur class at the Boston Business Exposition and was fourth with 78 wpm. In Chicago in September, Stollnitz lost to her Remington teammate Anna Gold, but reached a speed of 129 wpm. And in the world championships in New York on October 16, Stollnitz won the amateur crown with a brilliant 137 wpm over 30 minutes (with an actual average, before deductions, of 147.6 wpm). Gold was back in fourth place on 132 wpm, and speed typewriting’s future Underwood giant George Hossfeld fifth with 131 wpm. Woodson, who like so many before him had switched to Underwood, was eighth with 124.

Stollnitz’s success made Remington feel sufficiently confident to start matching Underwood’s big and bold advertising campaigns. Given Stollnitz’s pre-deduction speed of 147.6 wpm (compared to Owen’s 142.48 in winning the professional division), Remington was also laying claims to the world’s speed record. Owen had taken out her third world professional title in four years, this time with a record after-deduction speed of 136 wpm. She edged Oswald (136), Emil Trefzger (134) and Gus Trefzger (133). Ninth was a former Remington team member, Thomas Ehrich, using a then very new Noiseless.

RULE

CHANGE HITS STOLLNITZ HARDEST

At Hortense Stollnitz’s first exposure to professional competition, in the Eastern States championships in Philadelphia in April 1917, the Remington operator finished third equal with Friedman behind Oswald and Emil Trefzger, scoring 133 wpm to Oswald’s 135 and Trefzger’s 134. And staggeringly, in her first world championship at professional level, in New York on October 15, 1917, Stollnitz finished second on 142.23 wpm, marginally ahead of the far more experienced Friedman (142.21) and Oswald (141.78) and just 0.9 wpm behind Owen (winning her fourth and final world title) with 143.13 wpm. Emil Trefzger and Gold were tied for fifth on 140.

Remington and Stollnitz were, in the years after this event, to make much of the fact that Stollnitz’s gross score of 5544, 631 in front of Owen, amounted to an unmatched 159.1 wpm. But she made a massive 202 errors and incurred 1010 penalty points. Also, ominously, in 1917 Hossfeld won the amateur section with 145 wpm and Albert Tangora (above) took out the novice title.

Worse news lay ahead for Remington and Stollnitz. Organisers

of the world championships, sensing Stollnitz’s speed loomed as a threat to

Underwood’s stranglehold on the cup, decided to put more emphasis on accuracy

over speed and doubled the penalty rate for errors from five points to 10 ahead

of the 1918 titles. Earlier that year, in the Eastern States championships in

Philadelphia in April, Hossfeld headed Stollnitz, who was third behind Owen. Hossfeld

went on to win the world professional title at his first attempt, in New York

on October 21, scoring 143 wpm to edge Owen (142), Friedman (140) and Stollnitz

(136). Once more Stollnitz had a higher gross score than Hossfeld, but made a

now characteristic 87 errors and incurred the very high rate of 870 penalty

points.

Stollnitz (130.7 wpm) beat Hossfeld (129.9) yet finished third in the October 20, 1919, world championships in New York, marginally behind Owen’s 131.3 and Oswald’s winning score of 131.55. Again, Stollnitz had easily outscored Oswald, Owen and the other Underwood typists in the gross tally (8901 to Oswald’s 8383 and Owen’s 8482), but made 106 errors (to Oswald’s 49 and Owen’s 60) and was thus penalised heavily. Still, there was some good news for Remington in the amateur event, with Marion Carolyn Waner (above) emerging among four young Remington women, albeit well behind a comfortable winner in Tangora.

In spite of these encouraging signs, and with Stollnitz in excellent form early in 1920, Remington was fed up with the penalty rule change, which was clearly to favour Underwood’s ongoing domination of the world championships. Remington did not enter any of its typing team in the contests held in New York on October 25. This meant there was only one “outsider” among the 24 competitors across three classes at the world titles, Julius B. Fichtl operating a Noiseless in the amateur division; the other 23 typists all used Underwoods, including all four in the professional event. Hossfeld (131) beat Owen (128), Oswald (127) and Tangora (124) in an event which could hardly have engendered a great deal of excitement – even for Underwood.

Remington swallowed its pride and returned to the fray in 1921, and with renewed vigour. Stollnitz, who had been touring the US promoting the Remington 10 segment model, could only manage fifth (106 wpm) behind Hossfeld (136), Tangora (132), Oswald (128) and another Underwood team member, Genevieve Maxwell (124), in the world professional event at the National Business Show on 18th Street and Sixth Avenue on October 17. But Marion Waner took out the amateur title with 127 wpm, giving Remington its first triumph at the world championships since Stollnitz won the same title five years earlier. By 1922 Waner had overtaken Stollnitz as Remington’s major hope for a professional world title. In the championships at the Grand Central Palace, New York, on October 23, she finished fifth on 138 wpm, behind Hossfeld (144), Friedman (142), Tangora and Oswald (both 141). Stollnitz was sixth on 134. Again penalties were costly for Stollnitz (430), but even more so for Waner (570) and even for Tangora (630).

Having two finishers in the leading six in the top division must

have given Remington some joy. But by 1923 its ambitions to break Underwood’s

stranglehold on “The Thousand Dollar Silver Trophy” were at an end. Even

Underwood acknowledged this, and stopped its massive annual post-championship newspaper

advertising. Interest in the world championships started to drop off markedly

in the period between 1924-28. In the latter year, there was not a single

non-Underwood competitor among the 23 in the professional or amateur

competitions.

For all that, newspapers continued for many years to state

that Stollnitz’s 1917 159.1 wpm on a “self-starting” Remington 10 was the

fastest typing ever achieved under championship conditions. It quite possibly

still is, for a manual typewriter over one hour.

Hortense Stollnitz continued to work for Remington and travel throughout the US to demonstrate her typing skills, particularly to schools, until 1949 (the photo above is from 1939). On June 18, 1948, at the age of 50, she married real estate broker John L. Rogers in Manhattan. Rogers died, aged 77, in 1954. Hortense was still alive and living in Florida in 1967, but I can find no trace of her beyond that.

FOOTNOTE: Richard Polt has explained. “A ‘self-starter’ is a

typewriter which will start a paragraph ‘by itself’ (if you push the key, that

is). Unlike a true tabulator, it advances the carriage five spaces forward from

whatever your current position is.

4 comments:

Another well-researched article, thank you.

Amongst the Royal, Underwood and Remington brands, which do you think were the fastest machines for speed typing contests; or was it more about the typist than the machine? It seems each brand, at one time or another, touted themselves as being the fastest, but I wonder if there’s some objective data available to the typewriter historian.

Excellent post Robert.

This is the first I heard of Ms. Stollnitz even though I've read many articles on typing contests and find all of them interesting. I often wondered how much difference different manual machines make when it comes to speed and accuracy. I know I do better on USA made typewriters than on any Olympia. Underwood still being the best. I've often wondered the same as Joe asked.

Hello,

I am Hortense Stollnitz's great-niece. My brother happened upon this blog post and sent it to the rest of the family. We'd be happy to fill in some blanks on her later life, so I hope you'll get in touch.

Great-Grand Nibling here! Always so cool to read about my Aunt Hortence!

Post a Comment