Did anything rub off on to Herbert Woodend Clock when he slept in Samuel Johnson’s old room at Pembroke College, Oxford University? Well, to be honest, it was no longer exactly Dr Johnson’s old room by the time Clock moved into his Oxford digs in October 1910, having crossed the Atlantic in the comfort of a first-class cabin on board the California from New York City to Glasgow. The tower over the college gateway which housed Johnson’s room on its second floor had been replaced in Victorian times. Still, the people at Pembroke told Clock it was the same room which had been occupied, for 13 months from October 31, 1728, by Dr Johnson, and Clock, his family back in Freeport, Nassau County, and a slew of US newspapers were only too happy to believe it. Clock, in 1910, was a relatively naïve 19-year-old when he entered Oxford, just as Johnson had been 182 years earlier. But while Johnson went on to become regarded as “arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history”, Clock’s contribution to literature was, by comparison, far, far slimmer. The two differed in one other significant way - Johnson couldn’t afford to stay at Oxford; Clock had enough wealth behind him to travel back and forward to America over the three years he was at Pembroke, as well as to regularly traipse around the Continent.

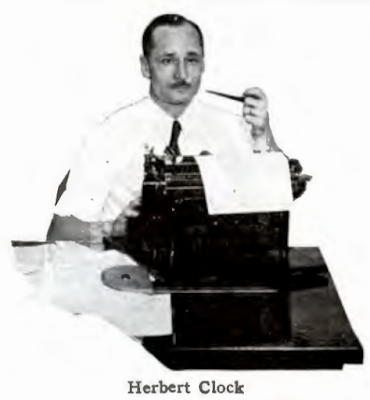

Clock is seen above at his typewriter after the publication of his 1929 sci-fi novel The Light in the Sky. Beside him in the original unrouted print was a Brooklyn attorney, Eric Boetzel, who in exchange for cutting Clock’s manuscript in half was bestowed with co-authorship. Goodness knows whether any reader would have been able to negotiate their way through the original work. Why I wonder whether anything of Dr Johnson rubbed off on to Clock is that Johnson also wrote sci-fi (or so some experts in that particular field claim). The Prince of Abissinia: A Tale (better known as just Rasselas) was written in 1759, primarily to pay off Johnson’s mother's debts and her burial costs after she had died, at the age of 90. The novel was written in the evenings of one week, and sent to press while being written. Johnson earned £125 in total from two editions, possibly round the same amount as Clock earned from his one edition in 1929, 170 years later. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction says Rasselas combines “elements of the French conte, the Oriental fantasy and the fantastic voyage” and that “the tale is of particular interest to the student of proto sci-fi for its sustained meditation on the nature of and chances of obtaining human happiness (see also Utopias; Dystopias). The initial setting of the tale is a secret ‘happy valley’ … a prison in which the offspring of Abyssinian royalty are sequestered, but from which Rasselas hopes to escape in a primitive airship (in the event it fails - Johnson's spirit was inimical to unsustained flights of fancy); also featured is an astronomer who believes himself responsible for weather control. The book is an archetypal example of the important sci-fi theme of conceptual breakthrough.”

Dr Johnson

Clock’s The Light in the Sky, on the other hand, is described by The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction as a "sci-fi tale set in an underground lost world extending from Mexico into the Gulf of Mexico, where Aztecs retreated after the genocidal onslaught of the Spanish and have constructed, over the centuries, a culture dominated by the possession of immortality, high science, telepathy, and - apparently - human sacrifice. The protagonist, lured from combat in World War One by a mysterious girl from this world, causes havoc … Though the immortal Aztec genius behind the throne has in fact some benevolent impulses, and has plans for interstellar exploits, the usual terminal disaster puts an end to this.” One Dutch résumé says, “the author finds himself telling [of a] strange, harrowing experience in a world unknown, during an illimitable time, the dreaded nights, the days of unspeakable suspense, the horrible alternations between hope and despair, the silent, repressed suffering, the haunting, ever-present dread of a thing he dared not name.” At the time it was written, Clock had been three years in his position as advertising manager for the Columbia Photograph Company, and his book came out with a theme song attached – a “first” in publishing, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The song was written by Anne Caldwell O’Dea, a playwright and lyricist who had previously worked with Jerome Kern and had written pop songs and Broadway shows, Robert Hood Bowers, a composer, conductor and musical director of operettas and stage musicals for Columbia, and Ben Selvin, musician, bandleader and record producer who was known as the Dean of Recorded Music and was artists and repertoire (A&R) director for Columbia. Publishers the Coward-McCann Company of New York were brave enough to believe the novel was headed for an adaptation for the silver screen.

Herbert Clock, right, playing rugby for the US against Romania in Paris in 1919.

Writing advertising copy was a long way from the promise Clock had shown at Mercersburg Academy, Pennsylvania, where from 1907-09 he was prepped for Oxford. He had graduated from Freeport High School in 1907 and in the Mercersbury academy prizes for 1908 he got honorable mentions for an essay on Washington Irving and for English. In 1909 he was named class poet. This was sufficient for Clock’s wealthy father to pay to send Herbert off on to the footsteps of Dr Johnson at Pembroke College, Oxford.

On the face of it, there was sporting ability and adventure in the blood of the Clocks, as well as a ton of money in their pockets. One of them, Nathaniel Oakley Clock, skippered the New York Yacht Club’s Mischief when it successfully defended the America’s Cup against the challenge of Canada’s Bay of Quinte Yacht Club, with Atalanta in 1881, a time when the yachts looked very different from those seen skimming above Auckland waters this year. Nathaniel’s brother was Herbert’s grandfather, Lorenzo Dow Clock, “an old-time Sandy Hook pilot in the days when they met ships off Newfoundland”. Herbert’s father, Harry Godfrey Clock, left, made a fortune when his shipping company went bust and he got stuck in what became Fairbanks, Alaska, in 1898. He struck gold, enough of it to be able to pick and choose where the rest of his life led. While Herbert was at Oxford, Harry rejected the Republican nomination for District Attorney of Nassau County on the grounds, as The New York Times reported in his obituary, that “he did not want to assume the responsibility of sending anyone to the electric chair”. And fair enough, too. And if he thought Herbert, the budding poet, was worthy of a hugely expensive classic English university education, so be it.

At Christmas 1912 Clock went back to France with a team of Oxford under-graduates called the Plutonians, which played Racing Club de France, among others. He had a busy schedule playing on a wing for Oxford University through January and February 1913 – appearing against nine of England’s leading clubs. Clock returned to the US in June. He enlisted in May 1917 and left the US in July 1918 as a first lieutenant in the Machine Gun Company, 10th Infantry Regiment. At 28, he played for the US team which lost 3-8 to France in the final of the 1919 Inter-Allied Games tournament – Clock scored the US’s only points with a try. In October 1921 Clock formed the New York Rugby Club. One of its earliest players, and a great advocate for rugby in the US throughout the 1930s, was George Robert Pfann, a Rhodes Scholar in the mid-20s. Pfann was twice named an All-American at Cornell and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame as a player in 1957. Alan Chester Valentine was the first American Oxford rugby Blue, in 1923, and went on to be a president of the University of Rochester who served in the Truman Administration as a Marshall Plan official and as the first head of the Economic Stabilization Agency. Frederick Lawson Hovde was the second American Oxford rugby Blue, in 1931. Hovde went to be a chemical engineer, researcher, educator and president of Purdue University.

Herbert Woodend Clock, born

on October 25, 1890, in Huntington, Suffolk, New York, died aged 88 on July 17,

1979, in Freeport, Nassau, New York.

1 comment:

Very interesting fellow. Thanks for the post Robert. I've gotten another book to add to my reading list.

Post a Comment