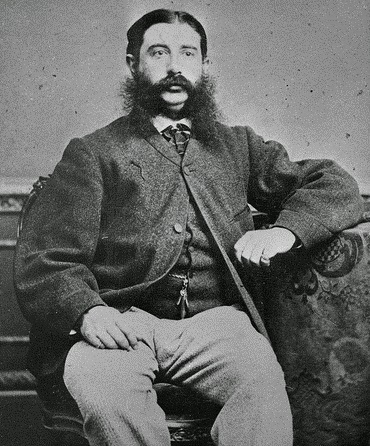

The funeral of South Australian writer Max Fatchen. His typewriter was called Ivan the Imperial.

DEATH IS ALL AROUND

I've often been told that the older I get, the more I should become accustomed to having friends, family and childhood heroes fall off the perch. Still, whenever it happens, it gives one a serious jolt, and a heightened sense of one's own mortality.There was a time, not so long ago, when I considered myself unfortunate enough to attend a friend or family member's funeral once in every three or four years. Now it seems it's four funerals every two months.

In the past months, four very close friends have died: a good and constant mate in Federal Capital Press head printer Barrie Murphy, historians Max Howell and University of Canberra emeritus professor Bill Mandle, and The Canberra Times' dearly beloved editorial assistant Julie Watt, a former member of Bob Hawke's staff when Hawke was Prime Minister.

Barrie Murphy

I will, of course, treasure fond memories of each of them. Barrie was born in Northern Ireland but came to Canberra from Christchurch in New Zealand. It was at The Canberra Times that Barrie lost the fingers on his left hand, after coming off second best in a tussle with a printing press. He continued played rugby and one day he and I were in a front row together playing against a team with an Australian Test prop called "The Iron Duke". At halftime the referee approached me and said the Duke had complained about eye gouging by our hooker. I turned to Barrie and said, "Murp, hold up your hand." Barrie did and the referee saw he had no fingers. Case dismissed, your honour! I still laugh when I think about that.

Max Howell

Max Howell also played rugby for Australia, as an immediate post-war centre. I can happily recall the time we spent together and the fun we had putting together a Sports Hall of Fame in Townsville many years ago.

Bill Mandle

Bill Mandle was another fellow sports historian and a fellow Canberra Times columnist. I admired him greatly for his pioneering and inspirational work in the field of sports history, but he went up considerably in my estimation soon after I joined the Times in 1997. He wrote in his column:

(Geoff Pryor is a nationally recognised political cartoonist)

Julie Watt

As our former editor Jack Waterford said in his eulogy at her funeral, Julie Watt always went to extraordinary lengths to help people. When I was putting together an exhibition of the models of typewriters used by famous authors for a Literary Festival at the National Library, I badly wanted a Hermes Baby and a red IBM Selectric. I had seen the Baby on the cover of a book of John Steinbeck writings, and the image of Johnny Depp, playing the part of Hunter S.Thompson, carrying the big red IBM.By chance I found the Baby in a most unexpected place (a recycling centre) the day the show started. Earlier, I had told Julie of my plight and she said, "I think we're got a red Selectric stored away somewhere." Many days later she announced, "Found it!" It was on the ground in a large stationery room, completely hidden under laden shelves. She dragged it out for me. I was proud to own it.

Doc Neeson of The Angels and Jim Keays of Masters' Apprentices put in major fights to hang on, as did Julie Watt (eight years with throat cancer; I was one of the first she told about it, and I feared she'd last but a few months). Yet each died far too soon. Barrie Murphy and Julie had both had just reached 60, Jim and Doc were 67. It's my age bracket.

Friday on my mind. Not his song, but Jim Keays died on Black Friday. I met him on a Friday and got to know him during this, the unforgettable Long Way to the Top tour.

Doc: Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again? A absolute classic. Basement blues.

Tommy died, just when I thought there were no members left of the greatest rock band ever.

Actress Wendy Hughes: ''I did but see her passing by. And yet I love her till I die.''

Either way, being able to so vividly remember watching these people play (both sportsmen and musos) has the effect of suggesting: Your time is coming, and perhaps sooner than you think.

The late Jack Brabham. Luckily, I did get the chance to meet him. A true gentleman. But gee, I can't tell you how much I yearned for Bruce McLaren to edge ahead of his teammate. I reckon McLaren ranks up there with Stirling Moss as the greatest Formula One driver never to win a world championship.

The late Reg Gasnier. Played for St George, the "Dragons", and was called "Puff" because he was the "magic Dragon". In 1965 I stood face on to him, only a matter of yards away, as with a subtle change of pace he ghosted through the defence for Australia. One of the very best. A nice bloke, too. Not all that many sports greats are.

Gary 'Gus' Gilmour, the wonderful all-rounder from Waratah, best remembered by me as a century-scoring left-hander, also for his bowling in the first World Cup final, in 1975.

I even had a kind thought for a politician who shuffled off this mortal coil. Neville Wran was a decent New South Wales premier, and one who also believed typewriters (even if electric ones) should be kept for posterity. The mallet was for other things.Don't get me wrong. I don't really fear death all that much. It may seem silly, but does keep me awake at night is the worry about the task I would leave behind, of friends and family trying to match typewriters with their cases and disposing, somehow or other, of the lot. I have seen the mammoth tasks left to Tilman Elster's son and Emeric Somlo's widow, and I do not envy them one little bit.

Anyway, before it's my turn, I'm planning to reverse Four Weddings and a Funeral and leave it, at least for the time being, at four funerals and a wedding. My son Danny and his partner Emily are getting married on November 1. Let's hope I make it that far! Then the vultures can hover!

.jpg)