Eugene Debs dictates while

his younger brother Theodore

types a letter on an Oliver typewriter.

Today’s Guardian Weekly

declares on its cover, “The Ascent of Bernie: How Sanders rose above the

Democrat pack”. This follows the Vermont senator's dominating performance in

Nevada last week. It certainly seems as if Sanders, like Eugene Debs before

him, is the man they can’t hold down. Mind you, I don’t expect Sanders, at age

78, will ever manage to emulate Debs’ effort in standing for the presidency a staggering

five times.

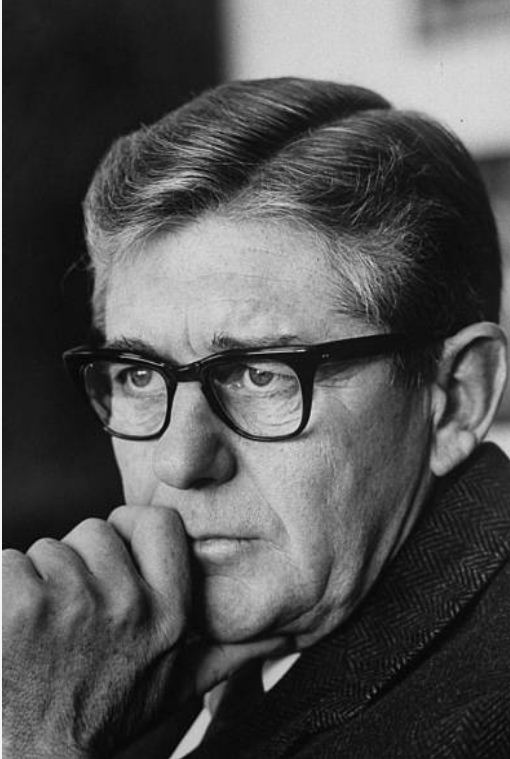

A much younger Sanders at a Debs exhibition.

Just

over a year ago The New Yorker published a 4347-word “A Critic at Large” article

from historian Jill Lepore titled “Eugene V.Debs and the Endurance of

Socialism: Half man, half myth, Debs turned a radical creed into a deeply

American one”. In it, Lepore pointed out, “Socialism has been carried into the 21st

century by way of Sanders, a Debs disciple, and by way of the utter failure of

the two-party system. Last summer [2018], a Gallup poll found that more

Democrats view socialism favorably than view capitalism favorably.”

A Remington typewriter at the Eugene Debs House in Terre Haute.

Saunders’

fasincation with Debs goes way back, wrote Leport. “The most

delightful way to hear Debs is to listen to a recording made in 1979 by Bernie

Sanders, in an audio documentary that [Sanders] wrote and produced when he was 37-years-old

and was the director of the American People’s Historical Society, in

Burlington, Vermont, two years before he became that city’s mayor. In the

documentary - available on YouTube and Spotify - Sanders, the Brooklyn-born son

of a Polish Jew, performs parts of Debs’s most famous speeches, sounding, more

or less, like Larry David. It is not to be missed.”

Among the Debs speeches Sanders recorded was the one in which Debs

spoke out against World War I soon after the US became involved in 1917. “I am

opposed to every war but one,” Debs said. “I am for that war with heart and

soul, and that is the world-wide war of the social revolution. In that war I am

prepared to fight in any way the ruling class may make necessary, even to the

barricades.” As a member of the Senate in 2010, Sanders repeated Debs’

sentiments. “There is a war going on in this country,” he declared in a speech

of protest that lasted more than eight hours. “I am not referring to the war in

Iraq or the war in Afghanistan. I am talking about a war being waged by some of

the wealthiest and most powerful people against working families, against the

disappearing and shrinking middle class of our country.”

Eugene Victor Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on November

5, 1855. This is a significant date for many folk in Britain and the old British

Empire: it is called Guy Fawkes’ Day, and marks the day in 1605 when Fawkes, a member

of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had

placed beneath the House of Lords in London, hoping to kill King James I. But that was more a religious issue than a

social or political one.

Deb,

socialist, political activist and trade unionist, was one of the founding

members of the Industrial Workers of the World. Ironically, early in his

political career, Debs was a member of the Democratic Party. He was elected as

a Democrat to the Indiana General Assembly in 1884. Debs was instrumental in

the founding of the American Railway Union, one of the nation's first

industrial unions. The 1894 Pullman Strike was ended by Grover Cleveland sending

in the Army and Debs was convicted and served six months in prison.

It

was to be the first of two spells behind bars. But from this one Debs emerged

as a committed adherent of the international socialist movement. He became a

founding member of the Social Democracy of America (1897), the Social

Democratic Party of America (1898) and the Socialist Party of America (1901).

Debs ran as a Socialist candidate for President in 1900 (earning 0.6% of the

popular vote), 1904 (3.0%), 1908 (2.8%), 1912 (6.0%) and 1920 (3.4%), the last

time from a prison cell. He was also a candidate for United States Congress

from his Indiana in 1916.

The Eugene Debs Memorial at Madison Square Garden.

Debs’ speech denouncing the US joining World War I led

to his second arrest, in 1918. Warren G. Harding commuted the sentence in

December 1921. Debs died in Elmhurst, Illinois, on October 20, 1926, aged 70, not

long after being admitted to a sanatorium because of to cardiovascular problems

that developed during his time in prison.