Total Pageviews

Monday, 31 May 2021

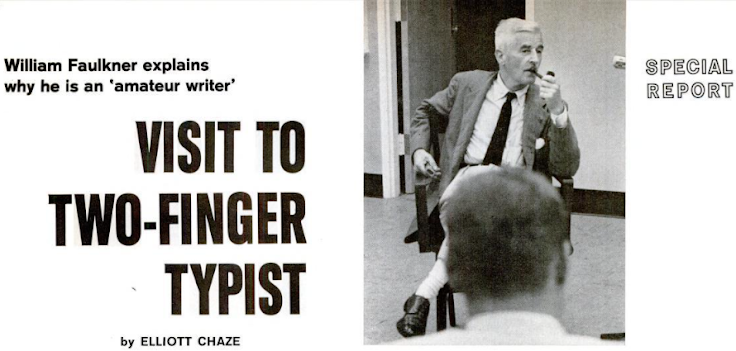

William Faulkner, the Two-Fingered Typist, and AI, 1962-Style

Sunday, 30 May 2021

C.J. Dennis and his Empire Typewriter: Bringing The Sentimental Bloke* Back to Life

*In Australia, a bloke is a unique masculine archetype

associated with the country's national identity. The "Aussie bloke"

has been portrayed in important works of art and associated with famous

Australian men. "He's a good bloke" literally means "he's a good

man".

I hadn’t realised, until after watching a brilliantly restored version of the 1919 Australian silent movie The Sentimental Bloke, that the verse novel upon which the movie is based was written by C.J. Dennis on an Empire thrust-action typewriter. The screenplay was also typewritten, in part by the movie’s female lead Lottie Lyell, using a Remington.

It turns out that in early November 1988, West Australian media magnate Kerry Stokes (a former rugby teammate of mine, and owner of The Canberra Times when I joined it in 1997) paid $8500 for Dennis’s Empire typewriter at a Leonard Joel auction at the Malvern Town Hall in Melbourne. How the South Yarra company had come by the Dennis typewriter is unknown, but the provenance is beyond doubt. That Dennis used the Empire at his home in Toolangi in rural Victoria was confirmed by his illustrator and friend, Harold Frederick Neville (Hal) Gye (1887-1967). The Empire is now part of the Kerry Stokes Collection, and features prominently in a video of Australian actor Jack Thompson reading excerpts from The Sentimental Bloke at https://watch.thewest.com.au/show/pub-100058

Clarence Michael James Dennis (1876-1938) published The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke in October 1915. It was an immediate success, requiring three editions in 1915, nine in 1916 and three in 1917; by 1976 57 editions had been published in Australia, England, the United States and Canada, covering 285,000 copies. A very human story, it was simply and humorously told in dialect verse which could be as easily spoken as read. Dennis said of this verse “that slang is the illegitimate sister of poetry, and if an illegitimate relationship is the nearest I can get I am content”. He had “tried to tell a common but very beautiful story in coarse language to prove - amongst other things - that life and love can be just as real and splendid to the ‘common’ bloke as to the ‘cultured’." The timing of the publication was important, as it reached a public depressed by enormous casualties at Gallipoli.

Our renewed interest in The Sentimental Bloke was piqued when we got the chance to see the restored movie last weekend at the National Film and Sound Archive's theatre in Acton in Canberra. What a brilliant job the NFSA has done with what it describes as our first rom-com. The images are crystal clear, the acting is wonderful, and the new narration by Rhys Muldoon is fantastic, as is the new score by Paul Mac. The film is mostly set in Woolloomooloo, Sydney

The movie was directed by Raymond John Walter Hollis Longford

(1878-1959), but much of the credit for it must go to his long-time partner Lottie

Edith Lyell (real surname Cox, 1890-1925), who plays Doreen, the Sentimental

Bloke's love interest. Bill 'The Kid' is played by Arthur Michael Tauchert

(1877-1933), and his friend “Ginger Mick” by Gilbert Charles Warren Emery (1882-1934),

who moved to Los Angeles in 1921 and stayed there for the rest of his life,

teaching in an acting school.

For the newly restored version of the movie, the NFSA had to search for and identify multiple sources to work from - including a digital scan of a pristine fine grain print from the George Eastman Museum in New York. The film was painstakingly brought back to life by NFSA experts and postproduction partner Vandal.

Saturday, 22 May 2021

Let’s Get it Straight: Seeing Pictures Isn’t Knowing, Reading Typewritten Word Pictures Is Knowing

Definition of word picture: a graphic or vivid description in words.

(Merriam-Webster)

Few of those of us committed to the Typewriter

Revolution might consider that their rebellion against the information regime,

their escape from the data stream and their choosing of the physical over the

digital has any connection with events in Gaza City in the past two weeks. Yet the

May 15 Israeli air strike on the al-Jalaa Tower, which housed news

organisations Al Jazeera and Associated Press, once more underlined the complete,

if vulnerable, dependence of such groups on the modern news media paradigm. Just

as Richard Polt pointed out on his May 9 blog post about a cyberattack on a

pipeline in the US showing typewriters remain necessary equipment for the 21st Century,

so too did the scramble to get equipment out of the al-Jalaa Tower raise

questions, at least in my mind, about digital writing tools. I was, for

example, stunned to hear AP’s president and chief executive officer Gary Pruitt,

sticking plaster on nose, say, “The world will know less about what is

happening in Gaza because of what happened today.” This was an alarming concession,

one that would have left many old form journalists absolutely gobsmacked.

Almost without exception, news coverage of the Gaza

air strike stressed the need for Al Jazeera and AP to get cameras out of the

tower after an Israeli advance warning. Not people, not writing machines, but

cameras. Bodies and brains apparently meant little by comparison, cameras were everything. Today, it

seems, news is not considered news without vision. Mere words just don’t cut it

anymore. The more the media depends on moving pictures, the more that great art

of creating detailed word pictures is lost. Am I alone in being unable to make

head nor tail of most news stories online these days? Reporters no longer seem capable

of writing stories that tell the reader everything he or she needs (and wants)

to know. Vital details are invariably lost in the rush to get unchecked articles

online. But, hey, there’s always a video or a picture, not that they necessarily

actually help much.

So, in effect, when AP’s Gary Pruitt was saying

in Gaza, “The world will know less”, what he really meant was “The world will

see less.” Seeing is not necessarily knowing. Knowing does not rely on

pictures. I can’t image the late 19th Century equivalent of a Pruitt telling

Lionel James, “We have to have pictures” when James, typing on a Blickensderfer

5, rode camelback into the Sudan with Kitchener. Nor when James, on a warship

in the Yellow Sea, filed blow-by-blow word pictures back to London during the

Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Journalists of James’s calibre needed no photos to

enhance their stories. Someone back in London drew dramatic images based on

what James wrote, so evocative were his articles.

Some of James’s successors were just as adept in

so accurately setting scenes in print. A.J. Liebling for The New Yorker

described D-Day on his Royal portable in such a way that, anyone who had read

his articles could watch Saving Private Ryan and say, “No need for

computerised special effects, for cinematic technology and digital bullet hits

and 40 barrels of fake blood, no need for 25 days of filming, a thousand extras

and $11 million to capture it. I’ve been there. I read Liebling, for the cover

price of The New Yorker.” And before Liebling, of course, there was the

Pennsylvania-born British knight, Sir Percival Phillips, capable of scooping

the world with a manual portable Corona in isolated Abyssinia. That took real

skill. To suggest someone like Phillips could only cover a warzone with the aid

of photos is simply laughable.

In 2003 I stood on the rim of an “elephant’s cemetery”

in Johannesburg, overcome by a sense of déjà vu, having been taken there

by the words French sports writer Denis Lalanne had typewritten on an Olivetti

Lettera 22, on that very spot 45 years earlier. It was uncanny. Not photographs, no

video I had seen of the scene had captured it the way Lalanne had. Photographs

and video couldn’t, because they were one-dimensional. Lalanne made his readers

feel the thrill and the tension of being there, looking down on that huge arena,

listening to the sound of ghostly silence, breathtaken by not just the vastness

of the place but its history. Now that was a picture, a word picture

par excellence. The typewriters of Lalanne, Liebling and James were nothing more or less than time machines. They took you places through time and distance, to let you see, and know.

No, the world need not know less about the

conflict in Gaza without cameras, or without modern communications. It would

have known an awful lot less without A.J. McIlroy, Max Hastings, Lionel James, A.J.

Liebling and Percival Phillips and their typewriters. Good journalists with

typewriters never failed to get their stories out, one way or another. They

always clearly understood, and mastered, their dual prime objectives: to get

the story and to get it out to the world. Would damaged television cameras have

impaired their ability to do this? Not one bit. The absence of any type of

camera only heightened their sense of the challenge they faced, their

obligation to accurately record history, and eked from them the very highest levels

of their abilities as wordsmiths.

Just today Al Jazeera reported accusations from Palestinian

non-governmental organisation 7almeh that social media companies had closely

cooperated with the Israeli Government to censor pro-Palestinian content after

Israeli attacks escalated. “There was a massive crackdown by Facebook,

Instagram and Twitter and other social media companies on posts relating to [peaceful

protests in the occupied East Jerusalem neighbourhood of] Sheikh Jarrah,” said Nadim

Nashif, director of the Palestinian digital rights

group. The ability to control news coverage of a conflict would have been impossible

in pre-digital days.

In the past few weeks we have had comments on

this blog from Ron Yates, for 20 years a foreign correspondent for The

Chicago Tribune, and a professor emeritus of journalism at the University

of Illinois and dean of the College of Media. Ron said he had used an Olivetti

Lettera 32 all over the world, covering “war and mayhem from Vietnam to Latin

America … It never failed me … I took it to some pretty awful places and abused

it in all kinds of situations.”

In a post about the Olivetti on his own blog,

Ron described taking his typewriter from the jungles of Cambodia to the central

highlands of Vietnam, jumping on and off helicopters, bouncing down rutted

roads in jeeps and trucks, and exposing the Lettera 32 to 110-degree

temperatures and monsoon rains. Like Hastings in the pub in Stanley, Ron’s

typewriter was “irrigated more than once with Vietnamese ‘33’ beer”. “Its

solid, blue metal shell behaved like armour plating. No matter how much I threw

that typewriter around or how often I dropped it, when I unzipped the vinyl

case and pulled it out, the platen always held my paper in position, and the

keys always worked. In 1975, this was state-of-the-art technology. Tough.

Dependable. Cheap. Easy to maintain.”

Ron said he had occasionally used the Olivetti

to shield himself “from airborne shrapnel and the other fluttering detritus of

war”. Ron weighed up the pros and cons

of typewriters versus laptops, mentioning the need for electricity for the

latter. What he overlooked was the vulnerability of digital communications. Manipulating

Public Telephone and Telegraph telex copy in transmission to Chicago was not

the simple matter it is with digital matter today. And then, of course, there’s

the question of the word picture. Oh, yes, in the digital age, that’s taken

care of by photographs and video. Without those “the world will know less”. Or

will it?

Saturday, 15 May 2021

Lech Wałęsa'd Into Submission, Among Other Admissions

So certain am I that there has only ever been one song written which included the name of former US Defence Secretary Robert McNamara in its title, I’m willing to bet a 1964 Olivetti Lettera 32 portable typewriter on it. The reason I'm tossing the Lettera 32 into the ring as the ante is because the song in question was written in 1964, at a time when the Lettera 32 was being widely recognised as the state-of-the-art writing machinery. It's also appropriate that while Robert McNamara was fanning the flames of war in Vietnam, the Lettera 32 was the work tool for journalists covering Vietnam, such as Argentinian Ignacio Ezcurra and his friend, the Italian Oriana Fallaci. And it wasn't meant for just war correspondents. One could take a Lettera 32 on to an artic waste or a mountain top or into a vast desert and use it to the content of one’s heart. The only ultimate impediment would be human, not mechanical – one might freeze or die of a lack of oxygen or a want of water, but the typewriter would just keep on going.

It is, of course, A Simple Desultory Philippic (Or How I Was Robert McNamara'd Into Submission). A desultory philippic, in case anyone out there is wondering, is a random tirade. The original version was performed and recorded in

At the end of

the 1966 recording, Simon says, “Folk rock”" and, "I've lost my harmonica, Albert" - referring to Dylan's manager Albert Grossman. The version recorded in 1965, however, has Simon singing,

"When in

Either way, in there somewhere, right about learning the truth from Lenny Bruce, I’m reminded what a joke it was that in my journalism career I was lied to so often by so many people - politicians, performing artists, ponces, sportspeople - that I sometimes lie awake at night wondering whether the liars ever got to lie straight in bed. I've been lied to by experts. At the time they lied, the liars stood up and lied to me, straight-faced, without a hint of shame. Not just me, of course - I shouldn’t take it so personally. But the really, really stupid thing is, we all knew they were lying to us when they did the lying. I haven't just been Robert McNamara'd into submission, I've been Gerry Adamsed, Lech Wałęsa'd and Geoffrey Rushed, Bob Hawked, Gene Pitneyed and Ben Johnsoned. And that's a few. There’s another line in Simon’s simple song, “I knew a man his brain so small, he couldn't think of nothin' at all.” I feel a bit like that man these days. The gullible guy who wrote tens of thousands of words to readers trying to convince them that I’d been told was true. I should be made to go and smoke a pint of tea.

Thursday, 13 May 2021

Reflections on My Feast That Turned Sour

According to Hilton Als, an associate professor of writing at Columbia University, writing the “On Television” column in The New Yorker last month, A Moveable Feast can’t entirely be taken at its word. Hilton claimed “The starving-artist myth that Hemingway put forth in his memoir … is one of several that the filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick debunk in Hemingway, their careful three-part documentary.” This premièred on PBS in the US on my 73rd birthday, April 5, and I very much look forward to seeing it when it reaches Australia. I will be particularly interested to see what it makes of Seán Hemingway’s “restoration”, if it mentions it at all. Als certainly doesn’t refer to the Seán Hemingway rewrite in his article.

When I became aware of what Seán Hemingway - son of Gregory (aka Gloria) Hemingway - had

planned, I devoted part of one of my own weekly columns to it. My gut feeling

back then was that A Moveable Feast would become a tarnished pearl. After

all, would anyone dare change Christopher Hitchens’ Hitch-22 in 2060? Or Joan Didion’s Blue

Nights? I began the column by outlining the reasons my own moveable feast

was ending with a bad taste in my mouth. This is what I wrote back then:

At about that time, I was asked to suggest techniques which might assist former readers, compositors and stonehands, linotype operators and typesetters to make the adjustment to journalism. I could think of no better method for them to learn to write stories in a concise yet descriptive and accurate way than to read Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. But, I hastened to add, it should be read in conjunction with The Essential Hemingway, in particular The First 49 Stories, so that the would-be reporter could see the startling results of the skill Hemingway developed and honed in Toronto in 1919 and in Paris in the early 1920s, while he was composing short pieces on conflicts in Europe to send back to the Toronto Star.

This last

part is highly contentious. Seán is claiming Ernest’s fourth and last wife,

Mary Welsh, cobbled together the last chapter after Ernest’s death. Yet there

is no evidence of this, and, indeed, Seán appears to have no proof his rewrite

more truly – to use a well-worn Hemingway word – represents Ernest’s feelings. Massie

pointed out, “This claim [that Mary Hemingway wrote the last chapter] has been

rejected by A. E. Hotchner, Hemingway’s friend, disciple, business and literary

associate in the last dozen years of his life. Hotchner, in an article in The

New York Times, insists that the 1964 book is very much the manuscript

which he himself delivered to Scribner’s in 1960, and that Mary had nothing to

do with editing or, more importantly, reworking the last chapter. Hotchner is

probably right. Nevertheless there is this to be said for Seán Hemingway’s new

version: that in April 1961 Hemingway wrote to Charles Scribner Jr to say that

the Paris book couldn’t be published in its present condition; it was unfair to

Hadley, Pauline and Scott Fitzgerald. But he also added that everything he had

since done to the book had made it worse.”

Massie’s judgment is that “the new version is full of explanations which weaken the impact, and which reek of self-pity. There is self-pity in the 1964 version too, but it is concealed behind a mask of stoicism. It is nastier, but it is also artistically right. It is effective because in this version Hemingway was true to his own artistic credo: that you can leave anything out, so long as you know what it is you are omitting, and the work is stronger for doing so. Massie argues the book should have been left alone. “Seán Hemingway may have done his grandma justice - but it is at his grandfather’s expense,” Massie concluded.

The [now

late] journalist Christopher Hitchens does not agree, and he gave what he calls

the “restored” edition a more glowing review in The Atlantic earlier this year [June 2009]. He did so partly because

some minor gaps in the original had been filled out, especially in relation to

sport and food writing. But Hitchens accepts the theory that Mary Hemingway

“pasted together” the Hadley-Pauline story after Ernest’s death, and generally applauds

the fact it has been rewritten. Hitchens, just as I had done back in the

mid-1980s, recommends reading A Moveable

Feast in conjunction with other Hemingway works. I suppose where Hitchens

and Massie coincide in their opinions of Hemingway, and of A Moveable Feast in particular, is in what Hitchens describes as

Hemingway’s talent (“I won’t say genius,” he writes) “in getting the reader’s

imagination to shoulder the bulk of the work”.

Massie is arguing the new edition lifts some of the burden off the reader’s imagination. If this is so, I will need to revise my standard advice to budding journalists*. The feast of practical guidance provided by Hemingway’s memoirs has, apparently, moved on, to something less nourishing. (*Indeed, any advice I've offered these past 12 years, since this column appeared in print, has been, "make sure you get the original edition".)

Monday, 10 May 2021

Typewriter Champs Denied the Chance to Emulate Babe Zaharias’ Olympic Glory

Frankly, I still can’t see the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games (rescheduled for July 23-August 8 this year) going ahead. Forging on with plans to stage the Games strikes me as reckless in the circumstances. But there need not be a cancellation, as there was for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics. On July 31, 1936, the International Olympic Committee, meeting in Berlin, awarded the 1940 Summer Games to Tokyo. The Second Sino-Japanese War, which broke out on July 7, 1937, intensified the next year and on July 15, 1938, the Japanese cabinet approved the cancellation of both the Summer and Winter Olympics. The latter were set down for Sapporo in early February 1940 and subsequently awarded to St Moritz in Switzerland then Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Nazi Germany. Like the Summer Games, they were not held. On July 19, 1938, Finland accepted the IOC’s invitation for Helsinki to stage the 1940 Summer Games, but these were cancelled on April 23, 1940.

Three weeks later, on May 13, the 18-year-old Esther Williams, the champion Californian breaststroke swimmer who had been considered a certain medallist at the 1940 Olympics, accepted her Olympic dream was over and turned professional. She joined the West Coast version of Billy Rose’s “Aquacade” a music, dance and swimming show. Williams replaced Rose’s wife, 1932 Los Angeles Olympics gold medallist, Eleanor Holm. Williams went on to star in “aquamusicals” for MGM, including portraying Australian Annette Kellerman in “Million Dollar Mermaid”. Williams wrote an autobiography with the same title. She died of natural causes in her Los Angeles home on June 6, 2013, aged 91.

By 1982, West Australian

athlete Decima Norman had come to fear war would interfere in her life twice. She

had been appointed custodian of the baton for that year’s Brisbane

Commonwealth Games, at a time when Britain was at war in the Falklands. “War

stopped my career before,” Decima said. “I hope it doesn’t interfere this

time.” Fortunately, hostilities ended in the Falklands on June 14, five days

before Decima flew to London with the baton. The baton relay started with the English

Queen handing it to a British runner, and Decima then brought it back to her

home town of Albany in Western Australia, from where it was relayed to

Brisbane. On September 30, with Decima watching on, Raelene Boyle brought it

into QEII Stadium and handed it to the late Duke of Edinburgh.

Dubbed by newspapers as “Dashing Des”, the “Silver Streak” and the “White Flash”, Decima was not quite in the Betty Grable league – nonetheless her legs were ensured for £500 when she returned to Sydney, this time to compete and settle there, in early 1939. Decima’s sprinting style was derided by all, included herself (she “ran like a hen in flight” according to her coach), but it was sufficiently adequate to carry her to gold medals at the Empire Games in the 100 and 220 yards, the long jump and in two relays. Her five golds remained a Commonwealth Games record until Canadian swimmer Graham Smith grabbed six in Edmonton in 1978.

Decima was an experienced and highly proficient typist and promises of work, including one at a newspaper, had lured her to Sydney in 1939, where she knew conditions and competition would boost her Olympic Games chances. She was ranked seventh in the world in the long jump in 1940, plus seventh in the 200m and sixth in the 80m hurdles.

The planned 1940 Tokyo

Olympics were cancelled five months after the Sydney Empire Games ended, and

Decima had then set her sights on Helsinki. Six months after the Finnish

Olympics were called off, Decima announced she was retiring from athletics. A

decade later her Australian records began to fall. Hours after being presented

with an MBE by Prince Charles on April 8, 1983, Decima was admitted to hospital

and diagnosed with cancer. After almost five months of treatment in Perth, she

died there on August 29.

Friday, 7 May 2021

In Praise of the Typewriter: The Early Days of American News Agencies

“By far the most important and valuable improvement in the efficiency of the electric telegraph in the past three or four years has been brought about by the introduction into telegraph work of a machine that has absolutely nothing electrical about it. While not all inventions that give added efficiency and greater advantages to the community contribute increased comfort to those required to use them, some rather entailing more laborious work or more fatiguing and trying conditions to the individual, the use of this invention has rendered easy and pleasant a class of work that was tiring and nerve-wearing in the extreme. The thing that has done all is the typewriter. This marvellous little labour-saver and life-lengthener has become absolutely indispensable in several of the more important branches of the telegraph service, a necessity to the complement of every first class operator, and soon its lively patter will be the unvarying accompaniment to the brisk clicking of the sounder in every telegraph office in the land.”

So wrote noted English-born journalist, and former telegraphist, Samuel John Pryor (left, 1865-1924) in his introduction to a lengthy article headed “The Typewriter: First Lieutenant to the Telegraph”, published in W.H. Temple’s weekly, the Electricity newspaper on December 9, 1891, and illustrated by H. Dearborn Gardiner. Given the typewriter, at its conception, was primarily aimed at just such work, it may seem odd that it took until 1887 or 1888 for its true virtues to become fully appreciated at major news agencies such as United Press* and Associated Press. Pryor says AP first introduced typewriters “as an experiment” into its offices in 1884, 10 years after the typewriter first went on the market. According to the article, UP and AP only started using typewriter “exclusively” in all their offices in 1889.

(*This United Press, formed in 1882, is not to be confused

with the later wire service which became known as UPI. The original UP collapsed

in late March 1897, owing the Western Union Telegraph Company $207,000, after New

York newspapers the Times, Herald, Tribune and Evening

Telegram, as well as the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, ditched UP

and switched to AP, leaving the New York Sun as UP's last user.)

Pryor quoted UP superintendent Frederick N. Bassett as saying “There has been a revolution in telegraphy” [Yes, a typewriter revolution!] Bassett went on, “It is the typewriter, backed by its ally the Phillips code, that has accomplished it.” (In Phillips’s 1897 book Sketches Old & New, the author rated Bassett as one of the eight best telegraphists he had ever worked with.)

The Phillips code was developed by Walter Polk Phillips (right, below, 1846-1920), like Pryor a journalist and telegraph operator. His was a brevity code which, for example, introduced to America the abbreviations POTUS and SCOTUS. Phillips was general manager of UP from 1882 until 1897.

Born in Grafton, Massachusetts, Phillips started work as a messenger with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1861. He became an expert telegrapher, noted for his speed in sending and receiving messages. Within three years he had risen to be a reporter in charge of copying AP news despatches. His skill caught the attention of Samuel Morse, who praised him for his “dexterity” in the use of Morse code as well as his “faultless manner of recording” messages. Phillips won telegraphy contests, in one setting a record by accurately transcribing 2731 words in an hour (45.2 wpm). He joined AP in 1867 and was made manager of its Washington DC bureau the next year. In 1875 he persuaded AP to establish America's first leased wire, for press service, linking New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington. Determined to make the AP the fastest news service in the US, he revised the existing abbreviations and codes used in the transmission of press stories and in 1879 published the first edition of the Phillips code. As an inventor, he patented an improved form of hand key and with Roderick H. Weiny invented a single line repeater known as the Weiny-Phillips. He was joint inventor of the first successful semi-automatic key, the “Autoplex”, patented in 1902 by Horace G. Martin.

Pryor pointed out that before typewriters were introduced to

these wire services, night reports in total averaged 8000 words and an entire

day’s reports totalled about 18,000 words. With the use of typewriters, the night

reports total rose to 14,000 words and the day’s total to 30,000 words.

Operators wired stories at 40 words a minute and with typewriters reporters

wrote reports at 70 words a minute. Producing carbon copies was also made significantly

easier. The Phillips code almost doubled output and on one occasion UP wired a

news special of 3500 words to all the newspapers receiving its service within

55 minutes. Typewriters improved the services immeasurably, allowing for longer

stories, more stories and later breaking stories. Remingtons were preferred (AP

abandoned all other models) but Caligraphs were also used.