One has to hand it to

indefatigable Imperial typewriter collector Richard Amery, of Sydney. He’s nothing

if not persistent in his relentless quest to find out what became of his

beloved typewriter company. “The truth is out there,” I can hear him cry. He still

believes there are questions to be answered. “What became of the … names Royal,

Adler, Imperial as far as branded portable manual typewriters from 1979 on?”

Richard asked in a comment on my last post. I thought that had been adequately

answered somewhere in the last three posts, but maybe not.

Well, just as Fox Mulder found there are some unspeakably

ugly creatures “out there”, I’m afraid the awful reality about Imperial is

similarly none too pretty. Richard is one of those few good men, but can he

handle the heartbreaking truth? Which is that no manual typewriter was made in

the Imperial name after Litton Industries sold the brand to Volkswagen in 1979,

and none after VW sold it to Olivetti in 1986. Tragically, it’s that

simple. Imperial manual typewriters were dead and gone by 1979.

One

of the main reasons for this is that as part of the Litton-VW deal, Volkswagen

acquired an 11 per cent holding in a British company called Office and

Electronic Machines, which had already been given British and Irish

distribution rights to Adler and Triumph typewriters by Litton in 1973. VW

obviously foresaw limited use of the Imperial nameplate (as it also did with

the individual Triumph nameplate) and had decided to put its faith almost

exclusively in the TA brand name and logo, including in Britain, Canada and

Australia. In Australia, where the company became known as Adler Business

Machines Pty Ltd, TA even advertised on the back of VW’s reputation for car

manufacturing. So VW, already burdened with manual typewriters at a time when

they were starting to be phased out, was more than happy to hand the Imperial

nameplate to OEM.

Imperial's Hull factory in 1971.

OEM,

incorporated in 1950, took over the business of the Imperial Typewriter Company

on March 1, 1975, a week after Litton had closed the last Imperial factory, on

Hedon Road in Hull. OEM changed Imperial’s name to Imperial Business Equipment,

headquartered in Leicester, though interestingly it continued to incorporate

the British royal warrant in its British advertising.

The Observer, October 28, 1979

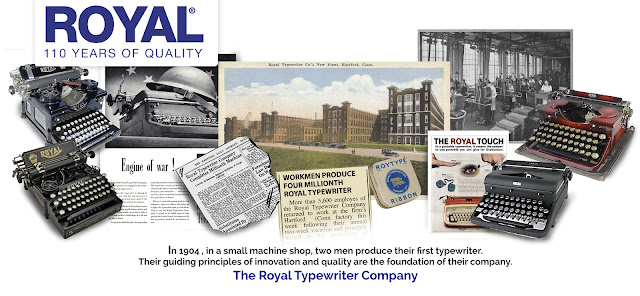

(The Royal Typewriter

Company, meanwhile, became Royal Business Machines Inc, based in the US under a

parent company, Triumph-Adler North America. In the mid-1980s RBM became part of a

joint venture between TA and Konishiroku Photo Industry Co of Japan, makers of

Konica cameras, photocopiers, fax machines and laser printers.)

Trouble at mill in Hull followed strike action in Leicester in 1974.

OEM’s

existing position as an importer and distributor of Adler and Triumph

typewriters in Britain caused considerable angst during the industrial dispute

which followed the closure of Imperial’s Hull factory. Laid off workers wanted

to continue making Imperial typewriters themselves, but ran into the problem of

distribution. A statement from the workers asked, “If the factories [Hull

and Leicester] are to be viable, a distribution mechanism must be found which

can market their product. At the moment, Litton thinks that it can pull out of

producing machines in Britain and yet retain the absolute right to market in

the United Kingdom the typewriters which they manufacture abroad.

“Office and Electronic Machines, a British

company, is presently expected to market Triumph-Adler machines,

manufactured by Litton's German subsidiary … the union is now seeking to

arouse public concern about this matter. One solution, it might be thought,

could be to nationalise OEM. Alternatively, OEM could be pressed, on balance of

payments grounds, to agree to become the representatives of the new Hull-Leicester

workers' enterprises. Whatever the solution which is finally agreed,

however, it is clearly quite improper for a trans-national company [Litton] to

abandon its productive obligations to a country, and at the same time expect to

exploit that country's markets unhampered in any way.”

Once the idea of a workers’ typewriter factory

had died its natural death, one ton (yep, 907 kilograms, no

less) of Imperial Typewriter Company files were purchased by Peter Tytell, left, son

of “Mr Typewriter, New York” Martin Tytell and himself a forensic typewritten

document expert. The Imperial files were shipped back to the Tytell Typewriter

Company’s second-floor office-laboratory-warehouse-workshop on 116 Fulton

Street, Lower Manhattan, near the Trump Building on Wall Street.

Martin Tytell

Peter

Tytell’s purchase was one of the few times in the period between 1979 and 1986

that Triumph-Adler or Volkswagen had anything to show for VW’s initial $26

million investment in Litton’s typewriter division. Put bluntly, the whole

exercise was a total disaster. In 1986 a Reuters story in the San Francisco Examiner estimated the

total of losses suffered by TA was $750 million in a crippling seven-year

period. The Examiner quoted analysts

as saying “TA might never have become truly profitable while it remained with

VW”. Yet as the parent company, VW had to bear that overall cost, while the market

failure was down to Triumph-Adler. OEM’s losses from whatever loyalty it had to the

Imperial brand name paled by comparison, but in the end OEM had to abandon its

Imperial typewriters in 1986, and never truly recovered. After three

appointments of voluntary liquidators in seven years, OEM finally bit the dust

in January this year.

The Guardian, October 11, 1975

The Guardian, September 26, 1979

At

the time of the Litton-VW deal being announced, it was said that Triumph-Adler

would “continue to operate with complete independence”. VW added that TA’s

“activities will continue unchanged and fully independent”. Which meant that TA

could deal with OEM on its own accord, including allowing OEM to use the

Imperial nameplate and royal warrant. It should be noted that both Imperial and

Royal were wholly-owned subsidiaries of TA, therefore TA could make decisions

for the two brands without VW’s involvement.

The Imperial SE 5000 CD

OEM continued to use the Imperial brand name for another

seven years. The last typewriter sold as an Imperial was a beast called the SE

5000 CD. It was a copycat golfball machine marketed in Britain and Australia in

1979 by Imperial Business Equipment Ltd.

The SE 5000 CD was also being labelled by manufacturers Triumphwerke

Nuremberg GMBH as a Royal. It was already being made at the time Litton sold a

controlling 55 per cent interest in its typewriter division to Volkswagen, on March

9, 1979 (authorised by the West German Government, June 12). It was sold in Australia by Raitt Adams, a company headed by George Raitt

which merged Imperial’s dealers in Sydney, Adelaide and Perth.

The Royal SE 5000 CD

About

seven years ago, someone in Dunshaughlin, County Meath, was selling one of

these Imperial SE 5000 CDs for 100 euros. It came with a “Pipman Wamsley” (sic)

commercial typewriter handbook, a cover, a mat and a cleaning brush. Not sure

if the enticing package is still available, but the cost of freight to Sydney

would be enormous. Still, Dunshaughlin (or more specifically, the townland of

Lagore) is famous for an ancient crannóg from the 7th century, where a number

of Irish antiquities were discovered. Maybe one day in the far distant future

cultural archaeologists will find the SE 5000 CD there, too.

OEM

used Imperial and Adler typewriters when in 1986 it developed the Screentyper, the

first office word-processing system that integrated “user-friendly” typewriters

with screen data processing, with optional telex and electronic mail handling.

The system was based on a Z80A microprocessor with 64K of memory and run by

OEM's own developed operating system. This was the last time the nameplate

“Imperial” appeared on new typewriters. In 1988 the Screentyper turned into

the TA VS 20 Videoscript system and TA’s “ultimate electronic typewriter” was

the SE 525 with expandable memory.

The Guardian, June 6, 1986

It

has to be accepted, regardless of our present-day feelings on the subject, that

in 1979 both Litton and VW were far, far more interested in the growing market

of electric and electronic typewriters than they were in continuing to make

manual typewriters. This was especially so as part of the development toward small

business and home computers (remembering the Commodore 64 didn’t come out until

1982, and went on to sell in the tens of millions). Before taking a majority

holding in Triumph-Adler, VW had been turned down in a takeover bid for Nixdorf

Computer AG, West Germany’s biggest computer marker and the fourth largest in

Europe (founder Heinz Nixdorf had worked for Remington Rand). VW’s TA

undertaking was, pointedly, described as “almost a second thought”.

The Guardian, January 22, 1980

United

States newspapers reported in March 1980 that VW had embarked on an “aggressive

diversification program to hedge fluctuations in car sales. Its objective is to

become a major force in the fast-growing office automation market – and

ultimately in the electronic office of the future. To meet this objective, VW

already has spent more than one-third of a billion dollars on acquisitions.”

These

included first Triumph-Adler as well as in October 1979 outbidding, to the tune

of $120 million, Dutch concern NV Philips for Pertec Computer, a producer of

small computer systems which led the world in computer-aided design and

manufacturing automation systems. VW was also eyeing companies with expertise

in digital communications.

Pertec

originally designed and manufactured peripherals such as floppy drives, tape

drives, instrumentation control and other hardware for computers. Its most

successful products were hard disk drives and tape drives, which were sold as

OEM to computer manufacturers, including IBM, Siemens and DEC. Pertec bought MITS,

the manufacturers of the MITS Altair computer, for $6.5 million in 1976 and

became involved in the manufacturing of microprocessor-based computers. It released the MITS 300 in 1977, a system which allowed for the Teletypewriter.

Pertec's final in-house computer design, the MC68000-based Series 3200, was extremely

advanced for the time. Soon after Triumph-Adler’s takeover, TA marketed the

system in Europe under its own brand with the model name MSX 3200.

In

1980 TA added Amdahl’s Eugene R. White to its board – Amdahl was an IT company

which specialised in IBM mainframe-compatible computer products. White joined

Pertec’s Ryal R. Poppa, left, who in 1981 was succeeded by Robert R. Nagy, president

of Royal Business Machines, who became head of Pertec as well as Royal, and CEO

of TA North America. Nagy was replaced by Edward E. Hale in 1984, with John E.

Stuart becoming president of Royal.

By

1981 VW had lifted its stake in TA from an original 55 per cent to 98.4 per

cent. And it was very much ruing having done so. TA, which had net earnings of

$10.9 million in 1979, lost $47.5 million in 1980. Naturally, when VW reported in

October 1981 a $12.5 million second quarter loss, its first loss since 1975, it

largely blamed TA. VW financial director Friedrich Thomée, taking the heat of

harsh criticism for his stewardship as policy board chairman of TA, resigned in

December. To make matters worse, Rank Xerox had decided to join the electronic

typewriter market in November (3M added itself to the field in 1982). TA was

certainly in trouble, and had closed its Frankfurt plant and laid off 2800

workers in September 1981.

TA's small 4% slice of the action: The Baltimore Sun, May 4, 1983

Things

didn’t improve in 1983, when losses of $11 to $13 million were still expected

by TA, albeit these were a two-thirds reduction from 1982. On top of this a

prolonged nation-wide cross-industry strike in West Germany in May halted TA

production.

Note the VW Beetle plate name: The Sydney Morning Herald, April 23, 1986

Judging

by its determination to hold on to TA North America, the United States was

possibly the one remaining bright spot for TA when Olivetti bought VW’s 98.4

per cent holding in the West German outfit in April 1986 (VW got a 5 per cent

stake in Olivetti in exchange). Worldwide in 1985 TA had sales of almost $1

billion yet still lost $60 million. TA North America had already sold Royal

Business Machines to Konishiroku Photo Industry Co in January 1986 (Konishiroku

took a 34 per cent stake in 1984) and Royal was renamed Konica Business

Machines USA.

Hartford Courant, January 20, 1985

But in the Olivetti takeover, VW initially held on to TA North

America (which owned Triumph-Adler-Royal Business Machines) and Pertec. The

fact that Olivetti spent $68 million on 98.4 per cent of TA while it cost VW

$280 million for 5 per cent of Olivetti says it all, really. And perhaps

Reuters was right – with TA in its stable, Olivetti announced in May 1987 that

its profit rose 12 per cent to $274.6 million. Yet a year later Olivetti’s

profit fell sharply because of losses at TA, with earnings falling 29 per cent.

In 1990 the Olivetti Computer Group cut its worldwide staff by 7000, including

4000 in Italy, citing weak demand for its product.

The Age, Melbourne, March 16, 1987

On

June 30, 1994, John Alexander Teong, secretary of Imperial Typewriter Sales Pty

Ltd in Sydney, declared the company dissolved. It hadn’t been doing any

business for more than a decade.

The Sydney Morning Herald, June 10, 1989

1992

1981