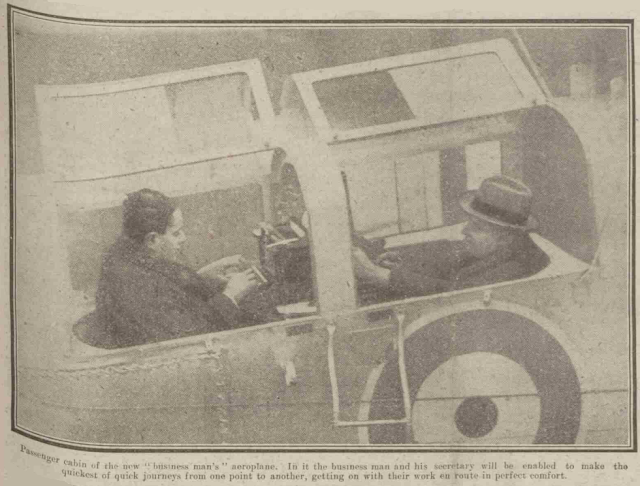

“The Business Man’s Aeroplane” had, in fact, been flying in Britain for almost a year before Topics caught sight of it. The first mention of an aircraft specially fitted for typewriter use that I can find appeared on the front page of the London Daily Mirror on January 28, 1919, with a large halftone under the heading “Up-to-Date Business Man’s Flying Office”. But this is clearly a Royal Air Force plane – the image shows it with an RAF roundel (the RAF was formed in April 1918) – and not the aircraft in the Topics images.

The aircraft in Topics was a Westland Limousine, a single-engined four-seat light transport biplane built for Westland Aircraft Works by Petter’s Ltd in Yeovil in south Somerset and powered by a Rolls-Royce Falcon Mark III engine. The first of these commercial aircraft took to the sky in July 1919. It was developed by civil aviation pioneer Robert Arthur Bruce (right, 1869-1948) as the “private motor car of the air”. Its use as a plane in which “a business man can dictate letters to his typist and sign the completed letter while on his way to his appointment” was publicised on August 2, 1919, after successful trial flights.

Between 1919 and 1921 there were many claims about the original use of a typewriter in the air, but this British breakthrough would appear to have got up there first. In the United States, Joplin, Missouri, editor Philip Ray Coldren (left, 1882-1955) claimed he was the first newspaper man to type a story in the skies after going aloft with French-born barnstormer Joseph Benjamin ("Joe Ben") Lievre (1888-1980) on January 13, 1921. Coldren had a Corona strapped to his knees when he entered his aviation cauldron. “I made up my mind to write something on a typewriter in an airplane and by the time we were 10 feet up I began. Every time we dipped a little I took my hands from the keyboard to grab the frame of the plane … I wouldn’t have unfastened the belt for the finest editorial inspiration in the world.” During a loop-the-loop the Corona’s carriage toppled over on to Coldren’s fingers.

This what Coldren typed during his flight:

“Well, here we are some

hundreds of feet off the ground with Joe Ben Lievre trying to do something new

under the sun. So far as we know there never have been any editorials written

in an airplane, though it strikes us as quite possible that some day in the future

the big editors are going to take advantage of this new system for getting clear

of Mother Earth for a nice quiet place to write. Why not? Up here there is some

noise, it is true, but they used to say of Horace Greeley that he could write

just as good an editorial with a brass band playing as in perfect quiet.

“This typewriter is showing

signs of engine trouble, but probably the trouble is with the engineer. Sure

hope it doesn’t fall down with us at this altitude (!) Just as we got this

written we ran into a heavy fog, which, of course, means that we are in a

cloud. Under the circumstances, a man’s thoughts might be expected to be a

little cloudy, might they not? But if one got used to it, he ought to be

inspired to write some real ‘high-brow’ stuff.

“One impression to be

gained from this altitude is that the entire district is pretty small, after

all. It seems queer that some of the people who live over toward the north

there should ever get it into their heads that their needs and desires are any

different from those people who live such a little way over to the south.

Probably if more people would take airplane rides they would have a broader

vision.

“There is another moral pointed by this airplane business, too, and that is that it is a lot pleasanter to go up and straight ahead than it is to go down. There is a sinking sensation that some portion of your anatomy registers when you start on the downward route that probably is not much dissimilar to the feeling of a man who wakes up after a morning of dissipation and feels he is on the way to Gehenna. [In rabbinic literature, Gehenna is a destination of the wicked.]

“Too many writers have

written about the wonderful view from an airplane to make any attempt of the

sort justified here, but it is a fact that a man up in an airplane gets an

entirely new idea of what a beautiful country southwest Missouri is. There may

be others equally as beautiful, but -

“Lievre just shouted back

that he is going to loop-the-loop –

“He did!”