A late contender for the much-coveted 2018 Typewriter Movie of the Year (Oscar nominations voting closes on January 14) is Can You Ever Forgive Me?, the biographical comedy drama based on Lee Israel's 2008 memoir of the same name. It stars Melissa McCarthy as Israel and follows the failed writer's fraudulent efforts to supplement her income by forging letters from deceased authors and playwrights. We saw the movie last evening and found it well-acted and entertaining, though the ultimate treatment handed out to Israel-McCarthy's typewriters was a major downer for me:

On July 27, 1992, Israel, realising "the jig was up" after being questioned by FBI agents outside a kosher deli, raced to the rented storage locker where she stored her "gang of typewriters" and "woke them up". She wrote in her book, "I deposited them, one by one, in trash cans along a mile stretch of Amsterdam Avenue, watching the traffic to see if I was being surveilled." Oh, to have been a typewriter collector wandering down Amsterdam Avenue that very day! (The image above is from the movie, and shows McCarthy ditching an Olympia SM9 in a bin.)

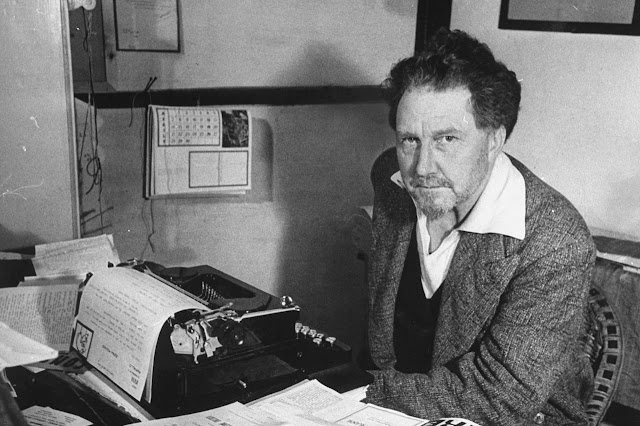

Above, the real Lee Israel. As for where she bought most of her typewriters, Israel wrote that she began the buy them in the first half 1992 "from a store in the West Twenties that sold vintage machines." This store appears to have been run by a man called Farber:

Back on October 6, Richard Polt of The Typewriter Revolution posted on Facebook that the movie, "looks like the most typewriter-heavy film since The Post. Did they consult my list of writers and their typewriters?" The short answer, Richard, is, "No!" The thought that - then or now - one of the Tytells might have been consulted doesn't appear to have entered anyone's head, either (Martin died the year the book came out, but Peter is still around). In the image at the top of this post, the eagle-eyed among you may note that Israel-McCarthy has labelled a Brother portable "Ezra Pound". This is what Pound actually used:

The first typewriter Israel-McCarthy buys in the movie, at the start of her criminal activity, is a Gossen Tippa Pilot. It's at the foot of the image at the top of the post, though out of focus. This specific purchase is presumably (as mentioned in the book) for letters purporting to be written by Dorothy Parker, though goodness knows why (other than Parker "having fun with the umlauts"). Yet in the movie it is labelled Noël Coward, the English playwright and composer,who did use just such a typewriter. McCarthy certainly needs a German-language keyboard, even if she doesn't type the letter ë in Coward's first name. The ë appears quite frequently on screen, but I'm not convinced that even a German keyboard Tippa had an ë key.

Later in the movie, Israel-McCarthy is seen using a different, earlier model Gossen Tippa:

The movie begins in April 1990 with Israel-McCarthy using her own Smith-Corona Electra 210 portable. Or trying to use it, I should say. She is suffering from writer's block (an affliction she has heard Tom Clancy dismiss out of hand at a drinks party put on by her agent). She types, “This is me f***ing using the typewriter.” Or not.

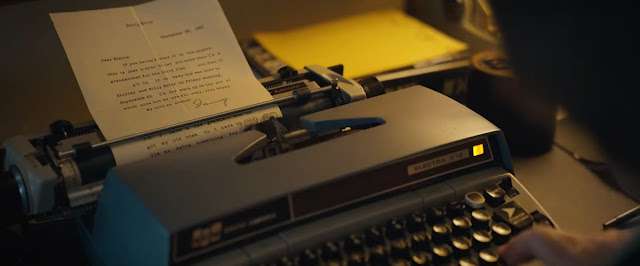

Astonishingly, Israel-McCarthy's first "bogus billet" is actually a postscript McCarthy types on to the bottom of what is supposed to an actual Brice letter. It reads, “My new grandchild has inherited my old nose. Should I leave something extra for repairs?” So the gormless mark is not supposed to be able to tell the difference between words typed on a manual typewriter sometime before 1951 (when Brice died; I think the letter is actually dated 1942) and a PS written on an electric portable typewriter (which didn't appear before 1957)? Someone has to be kidding, surely? After all, the real Israel was clearly very resourceful, and to a large degree the movie reflects this. At least Dorothy Parker lived to see the advent of electric portables, though not the Electra 210 (the Tytells would have seized on that in seconds, at one quick glance):

On July 27, 1992, Israel, realising "the jig was up" after being questioned by FBI agents outside a kosher deli, raced to the rented storage locker where she stored her "gang of typewriters" and "woke them up". She wrote in her book, "I deposited them, one by one, in trash cans along a mile stretch of Amsterdam Avenue, watching the traffic to see if I was being surveilled." Oh, to have been a typewriter collector wandering down Amsterdam Avenue that very day! (The image above is from the movie, and shows McCarthy ditching an Olympia SM9 in a bin.)

Above, the real Lee Israel. As for where she bought most of her typewriters, Israel wrote that she began the buy them in the first half 1992 "from a store in the West Twenties that sold vintage machines." This store appears to have been run by a man called Farber:

Israel rented a locker in an "ugly tattooed building" on Amsterdam Avenue. There she neatly stacked the typewriters on four wooden shelves - they were not, as the movie suggests, crowding out her apartment. The typewriter locker space "began to look like a pawnshop with a mighty distinguished clientele".

The first typewriter Israel-McCarthy buys in the movie, at the start of her criminal activity, is a Gossen Tippa Pilot. It's at the foot of the image at the top of the post, though out of focus. This specific purchase is presumably (as mentioned in the book) for letters purporting to be written by Dorothy Parker, though goodness knows why (other than Parker "having fun with the umlauts"). Yet in the movie it is labelled Noël Coward, the English playwright and composer,who did use just such a typewriter. McCarthy certainly needs a German-language keyboard, even if she doesn't type the letter ë in Coward's first name. The ë appears quite frequently on screen, but I'm not convinced that even a German keyboard Tippa had an ë key.

Later in the movie, Israel-McCarthy is seen using a different, earlier model Gossen Tippa:

Steve Kuterescz Collection

Israel wrote that, "I bought the first of a long and distinguished line of manual typewriters, a clattery, jet-black Royal [portable], old enough to have been used by Fanny [Brice] or, more likely, her secretary, from my neighborhood hardware store where various secondhand items were - still are - put on the street for quick sale: chipped china, worthless books, and old typewriters, the last singing siren songs to passing Upper West Siders nostalgic for the clatter of typing ... as opposed to the silence of keyboarding." Israel paid $30 for the machine and said its pica typeface was "similar to Fanny's." The first words Israel typed on it were, "Now is the time for Funny Girl to come to the aid of Lee Israel."The movie begins in April 1990 with Israel-McCarthy using her own Smith-Corona Electra 210 portable. Or trying to use it, I should say. She is suffering from writer's block (an affliction she has heard Tom Clancy dismiss out of hand at a drinks party put on by her agent). She types, “This is me f***ing using the typewriter.” Or not.

Astonishingly, Israel-McCarthy's first "bogus billet" is actually a postscript McCarthy types on to the bottom of what is supposed to an actual Brice letter. It reads, “My new grandchild has inherited my old nose. Should I leave something extra for repairs?” So the gormless mark is not supposed to be able to tell the difference between words typed on a manual typewriter sometime before 1951 (when Brice died; I think the letter is actually dated 1942) and a PS written on an electric portable typewriter (which didn't appear before 1957)? Someone has to be kidding, surely? After all, the real Israel was clearly very resourceful, and to a large degree the movie reflects this. At least Dorothy Parker lived to see the advent of electric portables, though not the Electra 210 (the Tytells would have seized on that in seconds, at one quick glance):

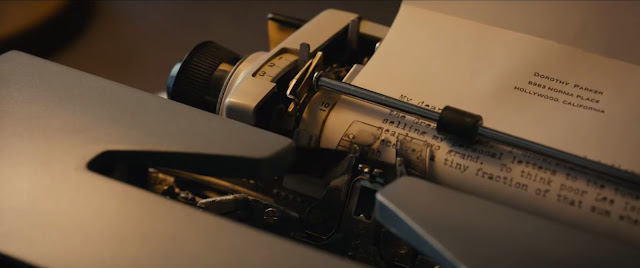

Dorothy Parker, typing on a Royal, and Alan Campbell at their farmhouse

in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1937.

Noël Coward on a very British Imperial in Jamaica in 1953.

Some of the forgeries (which Israel described as "her best work",

and much of which fooled the experts):