Total Pageviews

Thursday, 16 January 2020

Saturday, 11 January 2020

Tom Hanks Downsizing, Knocks Back Treasured Typewriter

Last week a retired library

director in Johnsburg, Illinois, posted on Twitter about an exchange of correspondence

she had had early last year with typewriter collector Tom Hanks. Marie Zawacki,

62, had offered Hanks her late father’s Erika portable typewriter to add to an already

sizeable Hanks collection. Mrs Zawacki said her father, Josef Metzger, had "smuggled" the Erika out of Germany when he immigrated to the United States as a World War

II refugee. Under the International Refugee Organisation, Hungarian-born Metzger

(1928-2017) arrived in New York from Bremerhaven in the then West Germany on the

USS General M.B. Stewart in early November 1951, and immediately settled in

McHenry County, Illinois.

Josef Metzger on the USS M.B. Stewart

On Facebook last February Mrs

Zawacki explained, “I found [the typewriter] in the back of a closet when

cleaning out [her parents’] house. [I thought it] might find a new home [in

Hanks’s collection]. I was able to ask dad about it before he died [in Woodstock

on April 24, 2017] and he said he brought it from Germany in his steamer trunk

and he wasn’t supposed to.”

Maria Zawacki with her late father, Josef Metzger

Mrs Zawacki wrote to Hanks through the Knopf

Publishing Group, which in October 2017 published his book Uncommon Type. Last

week she said “I will treasure Tom’s letter forever … It’s in an archival

quality frame, proudly displayed near the typewriter.”

In a warm, tactfully written

reply, Hanks turned down the offer of the “smuggle-worthy” Erika and said he

was downsizing his typewriter collection. He ended his letter with the words, “A

typewriter not in or with no personal connection is a story, a tragic one, in

and of itself.”

Sunday, 5 January 2020

The Lives Of Us (And Our Lethal Typewriters)

An early Torpedo 18, the typewriter of choice for East German playwright Georg Dreyman before he acquired a Groma Kolibri in the movie The Lives of Others.

Housebound by blistering heat

(111+ degrees, 44 Celsius) and a dense shroud of suffocating bushfire smoke, we

have found some brief hiatus in watching DVDs of old movies. First up was the

German language The Lives of Others, which I hadn’t seen in more than a decade,

since it first appeared on cinema screens. Back then I suspect I was so

engrossed by the appearance of the little green Groma Kolibri portable

typewriter with a red ribbon – which I had considered to be the true star of the movie - that I missed

many of the nuances in this brilliant work of art from Florian Graf Henckel von

Donnersmarck. Now, having watched it again and taken in much more of its rich

texture, I’ve been looking at reviews which had appeared in 2007. My favourite

movie reviewer is Anthony Lane of The New Yorker, and I thought this line of

Lane’s - from “Guilty Parties” in the February 12, 2007 issue - especially

topical and telling: “This [obligation to write about the terrible suicide rate

in East Germany] means smuggling in an untraceable typewriter - more lethal

than a gun, in the land of a controlled press - and smuggling out the copy.”

Some critics had apparently not appreciated the “humanisation”

of one of the two lead characters, Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler (played by Ulrich

Mühe). But with the benefit of my much later viewing – the viewing, I might

add, of a far calmer, more congenial viewer – I found myself agreeing utterly

with Lane’s appraisal: “One of the marvels of Ulrich Mühe’s performance - in

its seething stillness, its quality not just of self-denial but of

self-haunting - is that he never distills Wiesler into a creature purely of his

times. You can imagine him, with his close-cropped hair, as a young Lutheran in

the wildfire of the early Reformation, or as a lost soul finding a new cause in

the Berlin of 1933.” With 2020 hindsight, it's clear that one could also see Wiesler as a fundamentally decent man in these troubled times, increasingly compelled to resist the forces of blatant political corruption, bastardry and malice.

Not much has changed in 13 years - perhaps in a unified Germany, but certainly not in the Ukraine and not in the US of A. As Lane went on, “See [Wiesler] crouched in a loft above [Georg] Dreyman’s home

with a typewriter, a tape deck, and headphones clamped to his skull. Watch the

nothingness on his face as he taps out his report on the couple’s actions … Slowly,

the tables turn. Wiesler steals Dreyman’s copy of Brecht and takes it home to

read; he starts to omit details in his official account; and, for some

fathomless reason - guilt, curiosity, longing - he lets the lives of others run

their course.” As part of this engrossing process, Lane might have added

Wiesler’s listening to Dreyman’s piano playing, of Sonata for a Good Man from sheet

music given to playwright Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) as a 40th birthday

gift by the suicidal, blacklisted director Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert).

The superslim Kolibri

The

Lives of Others was released in 2006 and was the feature film debut of Donnersmarck

(whose name, Lane wrote, “makes him sound like a lover with a duelling scar on

his cheekbone in a 19th-century novel”). The movie went on to win the Oscar for

Best Foreign Language Film. Its ending

is one of the best I’ve ever seen in a movie. Lane summed it up well: “Against

all odds, though, the best is yet to come: an ending of overwhelming simplicity

and force, in which the hopes of the film - as opposed to its fears, which have

shivered throughout - come gently to rest. What happens is that a character

says, ‘Es ist für mich’ – ‘It’s for me.’ When you see the film, as you must,

you will understand why the phrase is like a blessing. To have something

bestowed on ‘me’—not on a tool of the state, not on a scapegoat or a sneak, but

on me—is a sign that individual liberties have risen from the dead. You might

think that The Lives of Others is aimed solely at modern Germans—at all the

Wieslers, the Dreymans, and the weeping Christa-Marias. A movie this strong,

however, is never parochial, nor is it period drama. Es ist für uns. It’s for

us.”

Not

only is it for us, but it is also – as I found to my great delight today – a film

very much for our times. It speaks to our present-day fears, in a world where

political corruption – in just about every major country one can think of – is more

rife and strident than ever before. The film unobtrusively signals the demise of

the Communist Bloc with a newspaper headline announcing Mikhail Gorbachev’s

elevation to Soviet presidency, but the end of the USSR has merely ushered in of

new era of extreme Right Wing Fascism and an almost universal undermining of democracy.

The Lives of Others is definitely well worth watching all over again. It very

much remains timely.

An East German forensic document examiner demonstrates different typewriter fonts to the Stasi.

A.O.

Scott wrote in The New York Times on February 9, 2007 (“A Fugue for Good German

Men”), Wiesler and Dreyman, as true patriots, needed to commit treason. And

treason is exactly what Donald Trump is accusing Democrats of committing in

their efforts to impeach him. Scott

said, “ … as Georg is driven toward

actions that implicate him, for the first time, in dissident activity, Wiesler

becomes convinced of Georg’s essential innocence and takes steps to protect

him. The plot, as it acquires the breathless momentum of a thriller, also takes

on the outlines of a dark joke. The poet and the secret policeman - both

writers, in their differing fashions - may be the only two true patriots in the

whole German Democratic Republic; in other words, the only people who take the

Republic’s stated ideals at face value. But since the nation itself functions

by means of the wholesale and systematic betrayal of those ideals, the only way

Wiesler and Georg can express their loyalty is by committing treason.” How

pointed is that in terms of the republic of the United States and its stated

ideals, and a “wholesale and systematic betrayal of those ideals” in 2019-20? East

Germany and the Stasi may be gone, but their ghosts appear to be living on, at least in

Washington DC.

Sunday, 29 December 2019

Tuesday, 24 December 2019

Monday, 23 December 2019

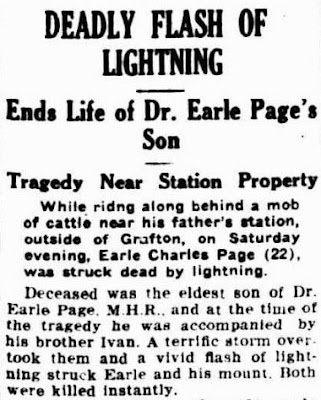

Not So Many Happy Returns: The Future Prime Minister's Typewritten Letter to a 'Noble' Son

On Boxing Day 1931, future

Australian Prime Minister and knight Earle Christmas Grafton Page (1880-1961) sat at his

typewriter in the Federal parliamentarians’ room of the GPO in Brisbane and

typed his eldest son, Earle Charles Page, a letter. The senior Page wished the

young man “many happy returns” on his 21st birthday, and congratulated Earle Jr

“on attaining your majority”.

Sadly,

Earle Jr was not to enjoy “many happy returns”, but just the one.

A

year and three weeks after Page had typed his Boxing Day letter, Earle Jr,

still aged just 22, was dead. On January 14, 1933, he was killed by a lighting

bolt while on horseback, driving 112 head of cattle with his younger brother

Iven (correct spelling) from Nettle Creek on the Baryulgil Road, 11 miles

outside Copmanhurst in the Clarence Valley of the Northern Rivers region of New

South Wales, between Grafton and the Page property Heifer Station (now a

vineyard).

Still,

young Earle had packed a lot into his short life. He had graduated from Sydney

University as a Bachelor in Veterinary Science in 1932, and that same year, as a lightweight wing

forward, had won his rugby Blue and played in two “Test” matches against New

Zealand Universities, as well as being a reserve for the NSW State team.

Page senior's Boxing Day letter was full of moralistic fatherly advice – “Avoid fast women” was one recurring theme. “Fast women,” warned the politician, “are the hounds of disease & death”. “Live as far as far as possible with noble thoughts … Live clean, think straight, act honestly, despise dirt & hate it whether physical, sexual, literary or spoken. Remember that you bear an honoured name …” “Do not drink till you are 45 & then you will not want to. Avoid every form of gambling, even the simplest, like the plague.”

Earle Page Snr at his desk in Canberra.

The

senior Earle Page and his wife were so traumatised by their son's death that Page immediately retired from politics. However, he later returned to Canberra and as Sir Earle Page became this nation’s caretaker Prime Minister upon the death

of Joe Lyons in 1939. He held the office for three weeks until Bob Menzies began

his first term as PM. In the House, Page was to accuse Menzies of ministerial

incompetence and cowardice for failing to enlist during World War I. Whatever

one may think of his overly righteous instructions to his son, in this case

Page was obviously a very good judge of character.

Page’s

letter to Earle Jr is on display in the Museum of Australian Democracy (Old

Parliament House) in Canberra, beside the “Yours Faithfully” exhibition.

Page Snr was the grandfather of noted Australian poet

Geoff Page (below).

Sunday, 22 December 2019

'Yours Faithfully' - Letter Writing With Typewriters

Last week we were invited to have a look at the way the "Yours Faithfully" exhibition at the Museum of Australian Democracy (Old Parliament House) had been set up. The exhibition, which had opened the day before (December 17th), is expected to continue until at least the middle of 2021. The curators have "held back" four of the 10 manual portable typewriters I either supplied or serviced, thinking it a good idea to have "fresh" interchange reserves for what they expect will be a steady fray of typing letters. Waiting in the wings for their turn to go into action are a Facit TP1, an Olympia Traveller, a Remington Envoy III and a Silver-Reed 100.

The six typewriters already out for use are evenly spread around the large room. I very much like the arrangement and the various posters on display. It's good that the curators (one of whom, by the way, comes from Richard Polt's home city of Cincinnati) have asked visitors to treat the typewriters with respect and kindness, and to take good care of them. That's not always going to be the case, we know that full well. But I'm on stand-by to make any running repairs that may be necessary. The first thing I noticed on entering the room was that little fingers can't resist playing with well inked ribbon - there were already black smudges over most of the typewriters. Sydney typewriter collector Richard Amery is also on stand-by, to supply new ribbons, as the stock at my local supplier has been exhausted (until March!).

The curators have a good collection of typewriter- and letter writing-related books to peruse, and they'll soon be adding Richard Polt's still highly-relevant "The Typewriter Revolution" to these shelves.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)