March 1 this year will mark the 100th anniversary of the long-awaited launch of the Blick-Bar frontstrike standard typewriter. Many typewriter histories list the Blick-Bar's birth as 1913, but the Blickensderfer Manufacturing Company's six-figure royalty deal with Syracuse auto maker Harvey Allen Moyer to use its Stamford, Connecticut, factory to make the Moyer typewriter was blocked on November 6, 1913, by two Blickensderfer directors, wealthy young New York businessman John Augustus Le Boutillier (1875-1924) and George Henry Bartholomew (who between them held more than one-sixth of the capital stock). The arrangement had been for Blickensderfer to make and sell the machine and pay royalties on it to the Moyer company.

Le Boutillier and Bartholomew said they were content with the gradual but growing returns on their investments in the low-price Blick typewheel portables and felt the gamble on a $100 standard-sized frontstrike machine "of undemonstrated merit" was far too risky. They feared the move might bring about the collapse of the Blickensderfer company, which was founded in Stamford in 1893.

At the time the Blick-Moyer deal was blocked, the Emmit Girdell Latta-designed machine was to be marketed as the Moyer, but in March 1916 it finally emerged - for the first time - as the Blick-Bar. In the meantime, advances to the mechanical features relating to ball-bearing pivoted typebars had been made by Moyer's typewriter department superintendent, Norwegian-born former long-term Underwood engineer Oscar Carl Kavle (September 9, 1870-). Le Boutillier and Bartholomew believed the patent rights, jointly held by Moyer, Latta and Kavle, had still be to be "determined and settled".

Le Boutillier and Bartholomew said they were content with the gradual but growing returns on their investments in the low-price Blick typewheel portables and felt the gamble on a $100 standard-sized frontstrike machine "of undemonstrated merit" was far too risky. They feared the move might bring about the collapse of the Blickensderfer company, which was founded in Stamford in 1893.

At the time the Blick-Moyer deal was blocked, the Emmit Girdell Latta-designed machine was to be marketed as the Moyer, but in March 1916 it finally emerged - for the first time - as the Blick-Bar. In the meantime, advances to the mechanical features relating to ball-bearing pivoted typebars had been made by Moyer's typewriter department superintendent, Norwegian-born former long-term Underwood engineer Oscar Carl Kavle (September 9, 1870-). Le Boutillier and Bartholomew believed the patent rights, jointly held by Moyer, Latta and Kavle, had still be to be "determined and settled".

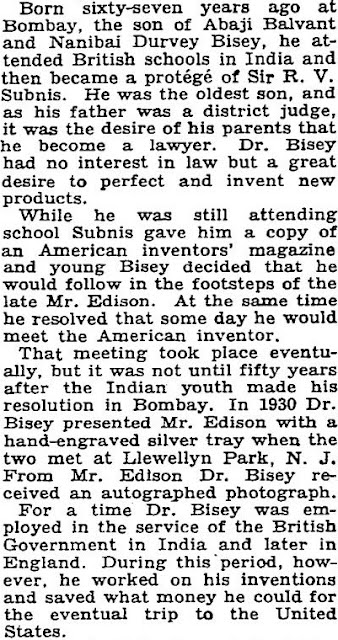

Above and below, Typewriter Topics, March edition, 1916.

Apart from the action of Le Boutillier and Bartholomew in calling a special meeting of Blickensderfer stockholders to rescind the decision to make the Moyer in Stamford, several other things had got in the way before the Blick-Bar eventually made its appearance. Not the least of these were George Canfield Blickensderfer's frantic work on the belt-loading mounted machine gun to be used in France in World War I (newspapers across the US reported that this hurried effort led directly to his sudden death on August 15, 1917, 17 weeks after the US had entered the war), the death of his first wife, Nellie, in June 1915, his remarriage, to Kate Helen Cochran, of Brooklyn, on September 21, 1916, the distraction of his sister-in-law Cecilia fighting to spare Amy Archer-Gilligan from a death sentence for multiple murders, and the massive order for the supply by Blickensderfer Manufacturing of typewheels for the Morkrum Printing Telegraph machine. Little wonder poor old George keeled over when he did.

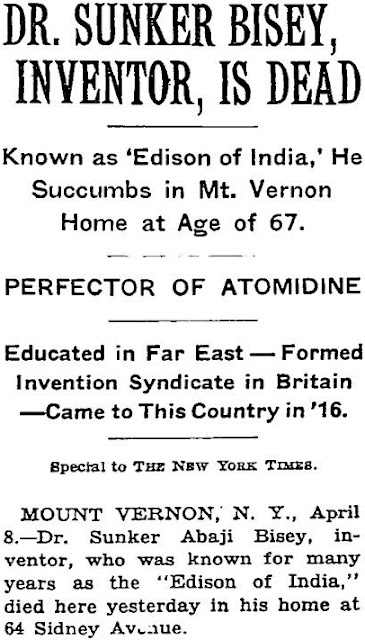

The New York Times, October 25, 1913

Legal and other problems related to the Moyer machine had obviously been sorted out by March 1916, to the point at which the manufacturer would also have naming rights. But production of the Blick-Bar lasted barely a year. After George Blickensderfer's death, what were originally the Moyer-Latta-Kavle patents and the tooling for the Blick-Bar were sold to Harry Annell Smith, who built a

factory in Elkhart, Indiana, to make it, but never did.

All lies and jest: Typewriter Topics, September 1916

Where the Blick-Bar did subsequently re-emerge was in England, where long-time Blickensderfer agents the Rimington family (by then running their own British version of the Blick company, as well as the British Typewriters Co and the Empire Typewriter Co) had models such as the British and the British Empire made by George Salter in West Bromwich in the early 1920s. This is the same company which also marketed such models at the Canadian-made Empire (originally Parker Kidder's the Wellington) and its variant, the German-made Blick Universal. The Rimingtons never had their own typewriter factory, unlike the Richardsons, whose Nottingham factory was taken over by the Jardines later in the 20s. Apart from Imperial, the only other major British typewriter plant until after World War II was Salters.

On the subject of the Stamford Blick company supplying the Morkrum Printing Telegraph machine with its typewheels, The New York Times reported on March 19, 1915:

Two interesting points regarding the cost of patents and of setting up production emerged from today's latest research into Blickensderfer and Latta. One is that it had cost George Blickensderfer $400,000 before he made his first machine, and in the preceding seven years the delay in starting manufacturing had eaten into the life of the original patents (in some cases by as much as a half). At that same time, it had cost Latta $10,000 for 67 patents, 46 of them for his famous folding bicycle.