“There’s

blood on my typewriter.”

Psychologist Dr

Joyce Brothers (1927-2013) in an interview with Rosemary Jones of the

Allentown, Pennsylvania, Morning Call,

April 11, 1993.

Typing

his “Sports Splutterings” column on a Woodstock in Cleveland, Ohio, Walter Lawrence

Johns (1911-2002), long-serving sports editor for the Central Press

Association, a division of King Features Syndicate, declared her the “new

flyweight boxing champion of the TV world”. She’d “kayoed a flock of

heavyweight questions” in a long count bout that matched Tunney versus Dempsey

at Soldier Field, Chicago in 1927, wrote Johns. Blonde psychologist Joyce Diane

Bauer Brothers, a 5ft tall, 101-pound, 28-year-old mother had, in a sustained campaign

of 20 months in the mid-1950s, seen off all other contenders and her challengers

to win a purse that would equate today to $1.24 million. The challengers

included former world light-heavyweight champion Tommy Loughran, a man who’d

beaten Jack Sharkey, Max Baer and James J. Braddock, all world heavyweight

champions.

Aside

from promotional photographs to celebrate her wins, Joyce Brothers never donned

a pair of gloves. On December 6, 1955, just turned 28, Joyce Brothers became

only the second person, and the only woman ever, to win CBS’s The $64,000 Question by answering seven questions

on the TV show. Brothers won another $4000 on June 24, 1956, by beating a

challenger to her title. On October 27, 1957, Brothers repeated her 1955 effort

by winning the $64,000 Challenge, for

a grand total of $132,000. Her subject each time? The history of boxing,

ancient and modern.

Joyce Brothers and Bobo Olson at the weigh-in

Brothers’

expertise reaped other rewards. Three nights after winning her first quiz

jackpot, she covered the world middleweight title fight between Sugar Ray

Robinson and Carl “Bobo” Olson at the Chicago Stadium for the United Press wire

service (the story she typed at ringside revealed Stanley Ketchel was her

favourite fighter, “although he was considerably before my time”). Hers is

possibly the only title fight report byline which started with “By Dr …” and

the words “I couldn’t have been more wrong” (she had tipped Olson to win). On

March 25, 1958, Brothers also became the first woman to commentate on a world

title fight on television, when she provided between-rounds “colour” for CBS

during the Robinson-Carmen Basilio middleweight bout at the Chicago Stadium.

The

Newspaper Enterprise Association wire service, in a nod to Damon Runyon, quoted

Mushky Magee of the International Boxing Club as saying, “This gal has to be 8

to 5 – that’s in man-to-man betting – to go all the way. Couldja imagine her

and all she got stuck in her cropper talking about percentages with Al Weill

[former matchmaker at Madison Square Garden]? She might wind up conning him out

of the whole building.” Sammy Richman added, “We all wanna know who’s gonna be

the dame’s manager.”

“Truly,

the typewriter of the heavyweights has been busy these days.”

New York newspaper heralding the coming of Jack

Johnson, 1906

For six solid days there’d

been talk of nothing but typewriters (with the odd old map thrown in). Then it

came time for me to leave Cincinnati, and Richard Polt drove me to the Union

Terminal. As we passed through Over-the-Rhine and across the West End, I

noticed we were on Ezzard Charles Drive. I was as surprised to see the

Cincinnati Cobra thus honoured (he was Atlantan by birth, a Buckeye by early adoption)

as Richard was than I knew of him. But then the conversation quickly got back

on track, because there’s a 1951 Press photo out there of Ezzard Charles sitting,

behind an L.C. Smith standard typewriter, at a newspaper sports desk.

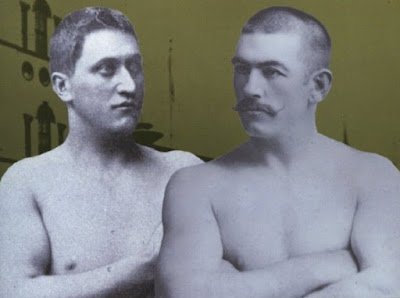

Herbert Slade and John L. Sullivan

Once inside the Union Terminal I soon found a wonderful

picture card of the Galveston Giant himself, John Arthur Johnson. But was

genial Jack really the first non-white to fight for the world heavyweight

championship? Oh, no. That honour belongs to the Māori Herbert Augustus Slade

(1851-1913), who faced the Boston Strong Boy John L. Sullivan before 12,000

people at the Madison Square Garden on August 6, 1883, five months after Slade

had given exhibitions in Cincinnati with Jem Mace. The Cincinnati Enquirer said of the Sullivan fight, “It is over, and

again the laurels of victory encircle the brows of the champion. Sullivan, our

pugilistic Alexander, having conquered all who dared face him from New or Old

Worlds, adds the antipodean scalp to his belt, and can now rightfully claim to

be the champion of the world.”

John L. Sullivan’s quick-fire bare-fisted jabbing on white

and coloured faces so impressed Kansas writer Joshua Short that in 1891, a year

before Sullivan relinquished the world title to Gentleman Jim Corbett, with

gloves and under Marquis of Queensbury rules in New Orleans, Short conjured a

machine called the “John L. Sullivan Automatic Typewriter” for a story titled

“A Typewriter Romance” in the Salina Vade

Mecum. A “beautiful and winsom damsel” called Rosalinda Matilda Fortier was

the agent for the Sullivan Automatic in Short’s little homily. A half-tone

illustration of the typewriter appeared on the lower left hand corner of the

wedding cards when Rosa married W. Wolsey Wycliffe. Sadly, the John L. Sullivan

typewriter never existed outside of Short’s fertile imagination.

A latter-day Joshua Short was Russell Baker (above), who died, aged

93, on January 21 last year. Baker was a columnist for The New York Times. In 1977 he wrote a piece satirising a Manhattan

party set-to between Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal, in which Baker matched Henry

James (“working out on the big typewriter”) with John L. Sullivan (“hanging

around James’s typewriter urging the great belletrist to discuss existentialism

…”).

“No

other subject is, for the writer, so intensely personal as boxing. To write

about boxing is to write about oneself - however elliptically, and

unintentionally.”

Joyce Carol Oates (1938?-) in her preface to On Boxing, 1987, written with a Remington manual portable

typewriter, or was it a Smith-Corona by then?)

What is it about typewriters and boxing? (And Joyces who are boxing fanatics?) Richard Polt, of

course, spent his formative years in Oakland, California, a place closely

associated with at least two famous typewriter-wielding boxing writers. Well,

one in particular: Jack London. The other was the man who gave the English

language the word “hype”, Herbert Anthony Aloysius “Hype” Igoe (1877-1945), who

came from Santa Cruz but spent time in Oakland. Igoe was considered by no less

an authority than Damon Runyon as “probably the best informed writer on boxing

who ever lived”.

The other Oaklander, London, grew up in the East Bay area but didn’t

write a lot about boxing. Yet by chance he came to cover arguably the most

significant bout in history, the one in Sydney on Boxing Day 1908 when Jack

Johnson became the first African-American world heavyweight champion. London

boasted in his fight story in The New

York Herald, “I often put on the gloves myself, and, take my word for it, I

am really delightfully clever when my opponent is a couple of stone lighter

than I am, half a foot or so shorter, and about half as strong. On such

occasion I can show what I’ve got in me, and I can smile all the time,

scintillate brilliant repartee and dazzling persiflage, and in the clinches

talk over the political situation and the Broken Hill [Australian mining] troubles

with the audience.”

“My

writing is nothing. My boxing is everything.”

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) in an interview with Josephine Herbst, Key

West, Florida, 1930.

Following in the shuffles of Jack London, many other writers have

put aside their typewriters and pulled on the gloves, most notably Ernest

Hemingway, Albert Camus, Vladimir Nabakov, Norman Mailer and George Plimpton

(the last two sat ringside together for the greatest bout ever, when Muhammad

Ali beat George Foreman in Kinshasa in 1974).

In

Paris in July 1922 Hemingway cajoled Ezra Pound into teaching Hemingway to

write in exchange for Hemingway teaching Pound to box. Hemingway and his first

wife Hadley also sparred with Gertrude Stein, until things got a bit ugly and

Stein drew blood. Pound and Hemingway were part of Stein’s The Crowd, which

jollied together at The Jockey. Another member was Mina Loy, whose Swiss-born

husband, Fabian Avenarius Lloyd (better known as Arthur Cravan), was a nephew

of Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde, whose lover, Lord Arthur Douglas, was

the son of the aforesaid Marquess of Queensberry, of boxing rules fame. Whether

this dubious connection emboldened said Lloyd-Cravan is not known, but in the

most brazen act yet of writer-crazily-takes-on-fighter, the begloved poet

Cravan entered a bullring in Barcelona and faced none other than the mighty Jack

Johnson. Johnson was, for the time being, cash-strapped and exiled in Barcelona,

and needed funds to hire two American jazz bands for the café he was running. Cravan,

described as a prototype for the Dada movement, was left gaga after six rounds

of Johnson gesticulating rather than jabbing.

By

comparison, Plimpton did actually go through the motions of boxing. In January 1959

Plimpton survived three rounds of “sparring” with the immortal Archie Moore in

Stillman’s Gym in Manhattan for a Sports

Illustrated story. There’s an hilarious blow-by-blow description by

Plimpton of the day Moore “kilt some guy” at Stillman’s at The Sweet Science. Did Plimpton offer himself up for further

humiliation, at the hands of “pound for pound, the greatest fighter ever”? It

seems like half a million online experts (including Wikipedia) will have us

think so, and that Plimpton also sparred with Sugar Ray Robinson – there’s even

a photo which purports to show a bloodied Plimpton with a laughing Robinson.

The truth is Moore felt he was too out of shape to play his 1959 self in the

1968 film of Plimpton’s 1966 book Paper

Lion, so the script was changed and Robinson, at age 48, stepped in and

sparred with Alan Alda, who was acting the role of Plimpton. Robinson was paid

$1500 for a day’s light work.

Plimpton had been inspired to face Moore after being told by

America’s Cup yachtsman Mike Vanderbilt in Palm Beach in 1958 about another writer

who’d challenged a champion boxer. And without a doubt, the funniest typewriter

pounder versus punchbag pounder mismatch was when Paul Gallico took on Jack

Dempsey while Dempsey was in Saratoga’s White Sulphur Springs preparing to defend

his world title against Argentine’s Wild Bull of the Pampas, Luis Ángel Firpo,

in September 1923. No so funny for Gallico, perhaps, but side-splitting for all

those who saw Gallico, down on all fours, trying to hang on to the canvas and stop

the ring from spinning backwards and forwards. Gallico, sent to Dempsey’s den

by the New York Daily News, looked

the part – he was 6ft 3, 190lb and had stroked the varsity rowing crew. But he

had never boxed. Hype Igoe warned him Dempsey never took it easy on anyone, and

the “bout” lasted 1min 37sec, most of it spent with Dempsey holding a groggy

Gallico up and dancing. Gallico wrote, “I was assisted from the enclosure and

taken some place else to lie down until my addled wits collected themselves

sufficiently for me to get to my typewriter. I had a splitting headache and was

grateful to be alive.”

Dempsey

might have made a dizzied mess of Gallico, but typewriters would, on behalf of

writers, soon have their revenge.

TO

BE CONTINUED

3 comments:

I only kown of Dr. Joyce Brothers from her radio programs.

Interesting about boxing and typewriters. Perhaps because they were the tools of the trade for the day, they were easily used ringside.

Brilliant article, Robert, as always. Some of this I knew but quite a lot I did not. Who would have thought Dr Joyce Brothers would have been an expert on boxing?

Impressive report! Thanks for working me and my cities into it.

Post a Comment