Today, April 10, is the 119th anniversary of the birth of my uncle, Walter Gerald Messenger MM, my father's oldest brother. If, as a child, I had had the chance to get to know him, I feel certain I would have idolised him in the way my father and his younger siblings had done. But almost 31 years before I was born, Walter Messenger had given his life for the freedom of the French and Belgium people, something the villagers in the border town of Nieppe remember to this day.

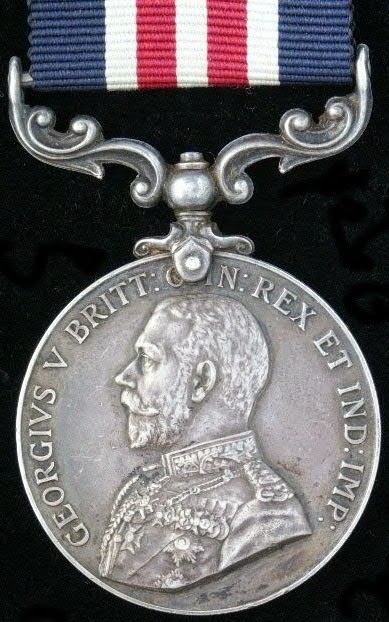

The MM after Walter Messenger's name stands for the Military Medal, awarded for his bravery in the field at the decisive Battle of Messines on June 7, 1917.

Walter is buried in the Pont d’Achelles Military Cemetery at Nieppe, in plot I, row C, grave six.

Walter Messenger’s actions on the first day of the Battle of Messines resulted in his award of a Military Medal being “promulgated” by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force on June 27, 1917 – 13 days after the battle ended and just 25 days before Walter died. The order for his decoration was issued on June 30.

According to the citation published in the London Gazette on August 16, 1917, Walter was to be decorated for helping to lay and maintain vital lines of communications between advancing troops and their supporting gun batteries. “We had many breaks in the lines but [Walter Messenger] was always ready to ... mend the breaks, in many cases under heavy shellfire from the enemy. Thus our communications were kept up and it was largely due to [Walter Messenger and Harry Waterford Minnis].”

The full story of Walter's bravery is not contained in the brief Gazette citation. But I had known it since I was a child of six or seven. And just this week, I found the more detailed account - one which coincided exactly with our extended family's long-held knowledge of what had occurred, and which memorably (for a highly impressionable young boy) had involved a dead German officer’s Luger P-08. It which was published in The Nelson Evening Mail on September 28, 1917.

Walter was also awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. All of these, along with his Military Medal, were presented to his mother, my grandmother, Emma Louise Messenger (née Boddington).

The Commonwealth War Graves' Pont d’Achelles Military Cemetery at Nieppe is maintained by the people of the village, who have large hothouses on site to grow fresh poppies to place on the Anzac graves year round. The cemetery was begun in June 1917 and used by field ambulances until the German advance the following April. It was used by the Germans during their occupation, under the name of the Papot Military Cemetery, and was resumed by the Allies in September 1918. The cemetery contains 293 Commonwealth and 37 German burials from World War I.

The Battle of Messines was ignited at 3.10 on the morning of June 7, 1917, when 19 large mines containing more than 447 tons of ammonal explosives were set off beneath German

lines on the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge. The explosion, which killed more than 10,000

German soldiers, was heard and felt as far away as Dublin. It was probably the largest planned explosion in

history until the 1945 Trinity atomic weapon test, and the largest non-nuclear

planned explosion until the 1947 British Heligoland detonation. The

Messines mines detonation killed more people than any other non-nuclear man-made

explosion in history. Smoke and dust from

the supporting Allied barrage limited visibility on the battlefield to 100 yards.

Walter Messenger survived Messines, but died in an Allied army hospital in Nieppe on the night of July 22, 1917, aged just 21 years and 14 weeks old. Earlier that day he had been hit by shrapnel from a German shell on the front line he had helped establish after Messines, west of La Basse Ville at Fromelles. On July 22, German howitzers had bombarded the New Zealand troops continuously for more than seven hours, from one in the afternoon until dusk, smashing into their trenches with 11-inch shells, as the Germans tried to reclaim lost ground on the Western Front.

Walter Messenger survived Messines, but died in an Allied army hospital in Nieppe on the night of July 22, 1917, aged just 21 years and 14 weeks old. Earlier that day he had been hit by shrapnel from a German shell on the front line he had helped establish after Messines, west of La Basse Ville at Fromelles. On July 22, German howitzers had bombarded the New Zealand troops continuously for more than seven hours, from one in the afternoon until dusk, smashing into their trenches with 11-inch shells, as the Germans tried to reclaim lost ground on the Western Front.

The heavier bombardment had started at 9.15pm on July 8, a fortnight earlier, and was concentrated on the centre of the trenches held by Walter's battalion, in the sector between Messines and the River Lys. There was no continuous line of trenches. The most advanced troops, of which my uncle was one, were in small outposts, which consisted of shell-holes connected up and adapted for defence, and which as a rule could not be approached by daylight. The intention had been to extend each post from either flank, as time went on, till all met in a continuous line. Walter didn't live to see that happen. His task had been to bury telephone cables in working areas that were so well forward that work could be done only at night, and the Germans shelled everywhere frequently. Casualties were high.

A German artillery crew firing a camouflaged 15cm gun at Arras, south-west of Lille. The shells fired at the New Zealanders were 28cm. Below, Allied troops unload 15-inch howitzer shells at Menin Road, Ypres, Belgium, in October 1917. These things could do some damage!

Walter, like many fallen soldiers, was unfortunate to be where he was the day he fell. The New Zealand battery had been ordered to take part in a practice battery, away from the extreme right of the front line and in preparation for the coming Third Battle of Ypres. But the German bombardment meant it was unable to leave its post. Walter's battalion, the 1st Canterbury, had only three days previously relieved part of the 49th and 50th

Battalions of the 13th Brigade of the 4th Australian Division on the front line, from La Truie Farm to a point midway between Trois Tilleuls and Loophole Farms.

Above, the pointer marks La Basse Ville, where my uncle was wounded by shellfire, and pinpoints Nieppe, where he is buried. The map below pinpoints the site of the Battle of Messines and Nieppe.

With the centenary of Anzac Day just 15 days away, I have been once more looking into Walter’s remarkable war record. He enlisted on April 17, 1915, one week after his 19th birthday. Walter lied about his age - he changed the year of his birth from 1896 to 1895, claiming to be 20 and therefore eligible to sign up. To cover his tracks, he used the address of the Empire Hotel in Blenheim, in the Marlborough province of New Zealand. He was in fact working as a shepherd much further south-west, at Molesworth Station near Hamner Springs, where his own uncle (his mother's brother) Robert

John Boddington was station manager.

Private Walter Messenger embarked for Egypt as part of the Canterbury Infantry with the 6th

Reinforcements of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force on August 15, 1915, with

less than four months’ training under his belt. He was to serve with the 1st Battalion Canterbury Regiment, which by the time of his death was part of the 2nd brigade of the New Zealand Division. Walter arrived in Mudros on the island of Lemnos,

Greece, on September 29, 1915. By November he was fighting at Gallipoli, in

the weeks before the evacuation, and spent Christmas 1915 back at Mudros. Walter embarked from camps in Egypt with the New Zealand troops on the Ascania on March 26, 1916, reached Alexandria on the 29th, and left the following day for Ismailia. On April 6, the 1st Canterbury Battalion arrived at Port Said, embarked on the Franconia on the 8th and arrived at Marseilles on the 11th, headed for the fighting on the Western Front. We can trace Walter's footsteps through Europe in Captain David Ferguson's The History of the Canterbury Regiment, NZEF 1914-1919, published in 1921.

From Marseilles Walter was taken on a 70-hour train journey to Steenbecque, south of Hazebrouck and west of Lille in central France. He went into camp at Morbecque. In early May, the NZ Division prepared for its arrival on the front line, and the 1st Canterbury Battalion moved to Estaires and then marched to Armentières outside Nieppe on May 13. On the night of May 20 it went into the front line. It must have been a terrifying experience for a young man, just turned 20. Walter's sub-sector included a salient known as "The Mushroom", described by war historian Ferguson as being "of evil memory". “The Mushroom” was forward of the trenches and at a point where the two front lines were only 60 yards apart.

After months of trench warfare in the Battle of the Somme, on October 1, as a preliminary to the Battle of Le

Transloy, Walter's battalion helped capture strongpoints near Eaucourt L'Abbaye. In February 1917 it moved to Nieppe,

as plans were put in place for the audacious Battle of Messines. One June 5, the 1st

Canterbury Battalion took over the tunnels in Hill

63, the now famous Catacombs near "Hyde Park Corner" in Ploegsteert Wood. Of course, my uncle never got to see the real Hyde Park Corner (in London).

A dummy tree used as an observation post on Hill 63, and below Australian solders at Hill 63, 1917.

At zero hour on the morning of June 7, the

leading waves of the 1st Canterbury Battalion left the

assembly trench, mostly (apart from Walter and his comrade Harry Minnis) in line in extended order, and advanced across No-Man's-Land

till they were checked by the Allied barrage on the German front line. The battalion's major objectives were the capture and

consolidation of the Blue and Brown Lines and included the Wytschaete-Messines Road and the strongpoint at Au Bon Fermier Cabaret. A specially detailed body of troops, of which my uncle was one, also set out for the houses on the northern

side of the Gooseberry Farm-Messines Road.

My own my interest in Walter was reignited on a visit back to my home town Greymouth in New Zealand in May 2003. On discovering, for the first time, where Walter was buried, I told family that visiting his gravesite would be like finding “part of who we are”. Upon returning to Canberra, I simply did a Google search for Nieppe. A website for the town came up, with an

email contact address. I wrote that I was interested to know about the cemetery

and its upkeep, as I had an uncle buried there.

Incredibly,

less than a day later I received five beautiful large, clear images of Walter’s

grave and others of the cemetery. Unbeknown to me, I had contacted Bernard

Decaestecker and his son Francois (above), who took care of public relations for the

village and had a very special interest in the cemetery and its upkeep. It

would be unthinkable, the Decaesteckers told me, that the cemetery would be

kept in anything other than pristine condition.

.jpg)

3 comments:

It's amazing how well-documented your uncle's life is.

A moment of whimsy amid the grimness is the kangaroo image at Hill 63.

A lovely and moving piece, Robert.

I don't know why, but it always brings a tear to my eye when I hear war stories of people willing to give their lives for the betterment of mankind. God bless your Uncle.

A good looking young man.

That's a big story of family history. A brave man, lying about his age to help fight for other peoples freedom and even getting a medal for it. Good to read Bernard's words too. Far too many people have forgotten already...

Post a Comment