Magic was provided by the

Maskelynes, maligners brought down Wier’s Pneumatic before it could even reach

production, and malfunctions proved the undoing of other British-made

typewriter concerns. In at least two cases, disgruntled investors hounded

typewriter companies through the English bankruptcy courts, disenchanted by broken promises of early and bountiful returns. Here is the last part of this series,

“The Great Typewriter Graveyard: Britain 1884-1904”.

HARTFORD: There

was a flurry of advertising in London and Newcastle-Upon-Tyne for the Hartford New

Model No 2 in early 1897, following a second visit to Europe by its inventor,

John Morrell Fairfield, in the middle of 1896. A Hartford Typewriter Syndicate

had been set up in England to market the machine, but only imported machines

were sold. Fairfield had established business contacts in the north-west of

England when he became the first US importer of British bicycles in the early

1880s.

Once an agent for the Caligraph, in 1887 Fairfield took over the American Writing Machine Company in Corry,

Pennsylvania, and moved the plant to Hartford, Connecticut, in 1888, patenting

improvements to the Yōst with English cycle maker Graham Inglesby Francis. Fairfield had met Francis on his trip to Europe in

1887 and Francis followed Fairfield back to Hartford. Fairfield sold Yōst to

the Union Trust in 1892 and formed the Hartford Typewriter Company in December

1893. He died in January 1901.

Once an agent for the Caligraph, in 1887 Fairfield took over the American Writing Machine Company in Corry,

Pennsylvania, and moved the plant to Hartford, Connecticut, in 1888, patenting

improvements to the Yōst with English cycle maker Graham Inglesby Francis. Fairfield had met Francis on his trip to Europe in

1887 and Francis followed Fairfield back to Hartford. Fairfield sold Yōst to

the Union Trust in 1892 and formed the Hartford Typewriter Company in December

1893. He died in January 1901.

MASKELYNE: The Maskelyne

was first seen at the Exposition Universelle, the Paris World’s Fair from May to October 1889. But it was another

four years before it reached the market. The father-and-son team of British

magicians, visionists and conjurers John Nevill Maskelyne Snr (below left, 1839-1917) and

Jr (below right, 1863-1924), of the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, patented this unusual machine

in Britain in 1894 and set up the syndicated Maskelyne Typewriter and

Manufacturing Company Limited in London. They produced the machine at Cadby

Hall, 72 Hammersmith Road, West Kensington, with showrooms at 41 Holborn

Viaduct. The Maskelyne went on show at the Belfast Arts and Industrial

Exhibition in March that year.

For

£27,500 the Maskelynes sold their patents, plant and stock to a new company,

Maskelyne British Typewriters Limited, in late June 1896, when a prospectus was

published. The chairman of the board of directors was James Mackenzie

Maclean (1835-1906), a former journalist and a Conservative MP from

1885-1900, first for Oldham and later Cardiff. Earlier, in India, he had owned

and edited the Bombay Gazette. John

Nevil Jr was also on the board, while Charles Laurence Baker (1853-) remained

works director. The company sought a massive £120,000 in share capital, which

given what had happened to other British typewriter ventures was ambitious to

say the least. Still, the new Maskelyne did go into production, though an initial estimate of 50 machines a week seemed optimistic. The target was 2600

machines a year, selling at £18 and realising £46,800. The cost of production,

royalties and advertising was estimated at £30,070.

For

£27,500 the Maskelynes sold their patents, plant and stock to a new company,

Maskelyne British Typewriters Limited, in late June 1896, when a prospectus was

published. The chairman of the board of directors was James Mackenzie

Maclean (1835-1906), a former journalist and a Conservative MP from

1885-1900, first for Oldham and later Cardiff. Earlier, in India, he had owned

and edited the Bombay Gazette. John

Nevil Jr was also on the board, while Charles Laurence Baker (1853-) remained

works director. The company sought a massive £120,000 in share capital, which

given what had happened to other British typewriter ventures was ambitious to

say the least. Still, the new Maskelyne did go into production, though an initial estimate of 50 machines a week seemed optimistic. The target was 2600

machines a year, selling at £18 and realising £46,800. The cost of production,

royalties and advertising was estimated at £30,070.

The Maskelyne typewriter plant at Cadby Hall, 72 Hammersmith Road, West Kensington.

The prospectus said, “The demand for typewriting machines has

greatly increased during the past few years, and the field for their employment

is unlimited. With few exceptions, the other machines on the market are either

wholly or partially made in the United States …” Advertising heralded “The dawn

of a new era in type writers” and emphasised differential spacing.

But

by 1897 the Maskelyne was in major financial trouble. In his The History of the Typewriter (1909),

George Carl Mares explained one important reason why. The machines were falling

apart with heavy use. While generally writing positively about the Maskelyne,

Mares did point out that typewriters needed to bear a good deal of vibration,

and to be able withstand that with moving parts that were extremely strong,

“and not liable to twist, shake or break. [The] refinement of parts necessary

in the Maskelyne would not permit of their being sufficiently strong, hence

after very little use, the machine failed to act. Either the escapement clutch

would not move far enough, or it went too far; the various universal bars

clashed and other mechanical defects showed themselves.”

By "refinement of parts" and “various universal bars”, Mares was underlining the Maskelyne’s need for four bars to provide differential spacing, as opposed to one in conventional

typewriters. The four bars Mares referred to were technically called

spacing-frames, which enabled the differential spacing, the main selling point

of the Maskelyne. Referring to changes in the third model Maskelyne, the

Victoria, Mares said, “It was a marvel of mechanism, but very few machines

were made and fewer still sold.” Differential spacing was, at least in part,

dispensed with.

As

with the Waverley (see entry below) the Maskelyne ran into huge problems with unhappy

investors. Maybe the world, at least the British part of it, wasn’t ready for

differential spacing. Clearly this objective needed much more work in order to

develop it successfully (indeed, 52 years’ work). It was a very fair goal, but

one which turned out to be beyond 19th century design engineers. Since it didn’t prove to be a key selling factor, Maskelynes and Waverley just didn’t sell in

numbers that might have sustained the companies. (Mares was to call the urge to provide differential spacing an “English fetish”).

Maskelyne Jr patented the typewriter.

By

early November 1897, the Marskelyne’s woes had reached the point at which a

shareholder’s petition was before Justice Sir Roland Lomax Bowdler Vaughan Williams, the same man who decided the fate of

the Waverley. The petitioner, Dyer, alleged all the Maskelyne’s capital

(£120,000) had been lost and a decision had been made for voluntary

liquidation. By February 1898 chairman Maclean (left) announced investments in the Maskelyne were being written

off and the bankrupt company was wound up in November.

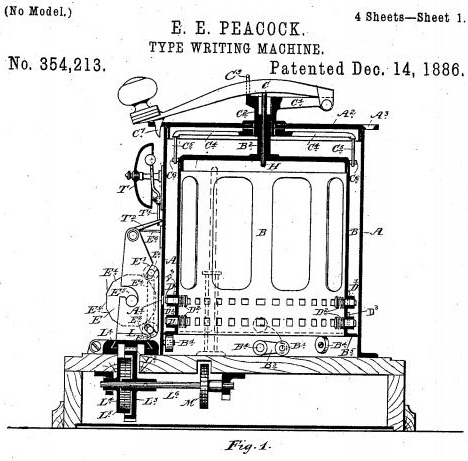

PEACOCK: Morning Post Fleet Street journalist and

founding member of the Institute of Journalists, Edward Eden Peacock (1850-1909)

launched a 6lb index manifolding typewriter with radical type plungers in late

May 1885, at the same time the Daw machine was being launched. The circular dial

was 4½in wide and 2¼in high with two circles of engraved characters. These were

inked by a roller. The Peacock came in a case 9in long, 7in wide and 5in deep. It

was patented in Britain in October 1884 and in the United States at the end of

1886. In 1894 Peacock became general manager of the Morning Post. He died in October 1909. Mark Adams says this machine

was also known as the Dial, but I can find no evidence of that, or that the Peacock went into production. However, a story in the London Times on May 26, 1885 (see below) would suggest it did.

London Times, May 26, 1885

PNEUMATIC: Nova

Scotia-born Marshall Arthur Wier (1844-1914), son of shipowner William McNutt

Wier, was an inveterate and rather eccentric English inventor. Ernst Martin

called him Weird instead of Wier (Weir was a much more common mistake). His Pneumatic

Typewriter Company, just one of his many ventures, was launched on November 24,

1894, seeking capital of £100,000 in £5 shares to produce the first compressed

air typewriter, selling at 12 guineas. India rubber balls would be used as

keytops attached to tubes and collapsible chambers, the expulsion of air

powering the trust-action typebars. Among the directors were George Frederick

Fry JP and French sanitary engineer Alfred Louis Lanseigne, as well as the inventor.

Mares

said the machine produced excellent typing. But sadly the air soon went out of

the project. Only 970 of the 20,000 shares were sold, and £1700 paid to the company

went to allotment. Investors had been put off by a seriously damaging article

which appeared on page 5 of the Pall Mall

Gazette two days after the prospectus had first appeared, and on the very same

day it appeared in the Gazette (on

page 10).

What made this bad publicity even more odd was that part of the prospectus quoted the Gazette as saying, in a September 13 review, that the pneumatic was the “bedrock of simplicity”. The September 26 story, written by “A Typewriting Expert” (who at least admitted he had an interest in a rival company) said, in part, “the principle of pneumatics, in the opinion of those best able to judge in the typewriter business, is absolutely unsuited for a rapid and reliable typewriter. The strain and wear which a typewriter has to bear can only be properly appreciated by those who have one in constant and continuous use.” The article ended by alleging Lanseigne was bankrupt.

What made this bad publicity even more odd was that part of the prospectus quoted the Gazette as saying, in a September 13 review, that the pneumatic was the “bedrock of simplicity”. The September 26 story, written by “A Typewriting Expert” (who at least admitted he had an interest in a rival company) said, in part, “the principle of pneumatics, in the opinion of those best able to judge in the typewriter business, is absolutely unsuited for a rapid and reliable typewriter. The strain and wear which a typewriter has to bear can only be properly appreciated by those who have one in constant and continuous use.” The article ended by alleging Lanseigne was bankrupt.

"Our weakest judge"

Lanseigne,

who ran a Paris sanitary system using pneumatic pumping, sued the Gazette for libel. By the time the case

reached the Queen’s Bench, in June 1896, jurors were told the Pneumatic

Typewriter Company “had been brought to ruin and disaster” and had been

“strangled at its birth”. In short, it had “come to grief”. The common jury

found in favour of Lanseigne, but Justice Sir William Rann Kennedy (1846-1915)

awarded Lanseigne a mere 40 shillings damages. The Gazette was then owned by the very wealthy William Waldorf “Willy”

Astor, the 1st Viscount Astor (below, 1848-1919), an American-British politician

and businessman, and one newspaper headline said, “Millionaire to pay 40s for

libel”. Vanity Fair called Kennedy

“Our weakest judge”.

London Times, October 22, 1889

The

Pneumatic Typewriter Company had gone into liquidation 10 months earlier, on August

21, 1895. In 1889 Wier, of Kingston-on-Thames, had also invented a small

Cryptographic typewriter for secret correspondence (see above). Twelve inches long by 3in

wide and 1½in high, it had an index plate and a type carrier and could also be

used as an ordinary typewriter. Again, a London Times story of October 22, 1889 (see above) indicates this machine was made.

RAPID:

At almost the same time as

Eugene Fitch was in London getting his typewriter made, English-born Bernard

Granville crossed the Atlantic to attempt the same thing with his Rapid. What

were they thinking? That the British typewriter industry was an untapped

goldfield? That British investors were queuing up to put their (largely

inherited, not hard-earned) money into typewriter ventures? Think again!

Lord Henry Ulick Browne

The prospectus for the Rapid Typewriter Company was published

in British newspapers on December 1, 1890, and offered 100,000 £1 shares. The

board of directors was headed by Lord Henry Ulick Browne, the 5th Marquess of

Sligo (1831-1913) as chairman, and included Granville’s older brother,

Clifford Kerr Granville (1863-1939). The company would “acquire and work all

the rights of Bernard Granville, of Dayton, Ohio, USA, controlling the Rapid

Typewriter for the whole world excepting the United States and Canada”. The

patent for the Rapid had been issued in Britain in 1888. The Rapid had been

manufactured by the Western Rapid Type-writer Company under Bernard Granville’s

management at a large factory in Findlay, Ohio, and had been “much appreciated”

for “some time past” in the US (“the home of typewriting”). Another company had

been formed in Montreal. Both were doing “rapidly increasing and profitable

work” and 2000 Findlay-built machines had been sold. The British company would

have the services, tellingly, of a “specially qualified” American engineer to

establish and fit up their factory to “make the most rapid, accurate and

automatic machine yet designed”. There was a “moderate” expectation of average

annual British sales of 5000 typewriters. Shareholders and their families could

get jobs at the plant and free lessons in using the rapid Rapid. Mares

demurred, quoting another writer as saying “the most rapid feature about the

Rapid was the rapid manner in which it disappeared”.

"In order to secure alignment, each bar travelled through its own

apertures in two guide plates ... " Mares.

One of the major drawbacks, Mares pointed out, was that a mere

£15,000 of the capital would initially go toward working costs and £75,000 to

Bernard Granville, £41,000 of it in cash! As it turned out, Mares added,

Granville only got £2000 and a “neat little profit” of £73,000 found “its way

into the pockets of the promoters”. Thus the prospect of Rapids being made in

Britain very rapidly went down the rapids.

At least Salter had something to crow about. It lasted far longer than any of the other 19th Century British typewriter ventures. Still, the "Yankee" produced far, far more typewriters, and far, far better ones too.

SALTER: The

Salter was arguably the only relatively successful typewriter launched in

Britain during this dire 20-year period. At least it lasted, in ever changing

forms, well into the 20th Century, even if it wasn’t made in enormous numbers.

But in this case, the company had a very solid foundation - George Salter and

Co Ltd of West Bromwich had been around as a highly successful operation making

valve springs, spring balances and weighing machines since the latter part of

the 18th Century. As Typewriter Topics said in 1923, “The English workmanship as exemplified in the Salter typewriter has always been excellent ...” - what a difference an established plant made! The Salter family business was eventually to allow a Salter

Typewriter Syndicate to be registered in early April 1896, with capital at a

far more modest £12,000 (given a well-furnished plant already existed). In

1903, by which time sales of the company’s second model, the No 6, had begun to

sag, George Salter and Co Ltd decided to take back control of the typewriter’s

sales from the syndicate.

The

family history claims “Salters was the first firm to make the typewriter in

England, for many years the only firm to produce an all-English model and in

the face of intense competition from abroad, to persist in its manufacture from

1895 to 1936, when the department became a separate company*.” This is

obviously untrue, in as much as the Daw, English, Gardner, North’s, the Maskelyne and even

Fitch 2 machines preceded the Salter. Also, Salter production ended in 1923,

following a five-year break because of World War I. The family legend dates the

first Salter typewriter, the Salter 5, to 1895, but it did not appear until the

following year, at a cost of eight guineas. (Many historians say the first

Salter was made in 1892; the actual year was 1896.)

A 1916 passport photo of James Samuel Foley, inventor of the Salter.

The

early Salter typewriters were designed by James Samuel Foley (1854-), a

mechanical engineer who was born in Cheshire, Connecticut, south of the home of

American typewriters, Hartford. Foley moved to England in 1889 and finally settled

and married in West Bromwich. Foley had first patented printing devices and

typewriters in 1889, and his original Salter design of 1892 was his alone

(while still in London) and unassigned. It did him little long-term good to

sell the rights to Salter, as he went bankrupt in 1915 and returned to the US

the next year.

The Satler factory after it started producing the British Empire standard typewriter, post World War I.

In

October 1896 Salter opened new London headquarters at 7 Newgate Street. The No

6 model came out in 1900, the No 7 in 1907, the No 9 (wide carriage) in 1908

and No 10 in 1910. Twelve hundred Salters were sold in one order alone, to

Germany in 1909. But until there was a complete change in design to a visible writer in

1913, it is estimated that only 22,000 downstrike Salters were ever made.

*Bill Mawle’s British Typewriters company.

A 19th Century typewriter for the blind. A Tangible perhaps?

TANGIBLE:

The Tangible Typewriter Company of 35 Queen Victoria Street, London, was

announced to the public on July 17, 1895. It was said to be already manufacturing

a typewriter “for the use of those afflicted with blindness”. The machine typed

in raised characters and would enable the blind to correspondent with others so

afflicted. “This Tangible will also prove a source of pleasure and amusement to

the wealthy blind, at the same time providing a means of increasing the incomes

of the indigent,” wrote the Pall Mall

Gazette. The machine was of simple construction. Michael Adler is of the

opinion is was never made, but says it was “appropriately named”.

WAVERLEY: The

Waverley got itself into all sorts of financial and legal trouble after the company was set up at 11 Queen Victoria Street, London, in early 1897. The 18½lb machine

may have looked “handsome and beautifully engineered,” in the words of Martin Howard, and certainly, when Mrs Charlotte Cuffe of Coventry won the National Union of

Typists examination in London in April 1895, using a Waverley and scoring 93

marks, 16 ahead of her nearest rival, things did look quite rosy for the Waverley. From May 1896 it was

advertised as “The Best Type-Writer (British Manufacture)”, the ads promising

“Writing instantly visible, differential spacing as letterpress. Terminal

spacing. Good manifolder. Universal keyboard. Every machine guaranteed.”

But in a little over a year events had turned decidedly against

the company. It was to spend most of 1897-98 in the Lincoln’s Inn courts, relentlessly pursued for money by Irish creditor Henry Vassall D’Esterre

(1840-1914) of Rossmanagher House, Bunratty, County Clare. D’Esterre’s petition

in early June 1897 led to a decision by Justice Sir Roland Lomax Bowdler Vaughan Williams for a compulsory winding up order. On

July 13 statutory meetings of creditors and contributors were held at the Board

of Trade on Carey Street before Assistant Receiver Henry Martin Winearls. The

Waverley company had a “total deficiency” of £45,473, including unsecured debts

of £18,454 and loans on debenture bonds of £6200. Its assets were valued at

£6996. D’Esterre, a debenture holder, insisted further debentures were owed to

him in respect of loans he had made to Waverley Ltd, which if proved true would mean

all the assets would be absorbed and unsecured creditors and those with

preferential claims for wages would get nothing.

After

a series of appearances before the Queen’s Bench Court, on September 20 the

company faced an official receiver to settle a list of contributories. The

legal battle against D’Esterre continued throughout 1898, but to no ultimate

avail. The Waverley was financially doomed and irrevocably headed for the hands

of receivers.

The Waverley was the work of two English engineers, Henry

Charles Jenkins (1861-1937) and Edward Smith Higgins (1842-1923). They formed

the Higgins and Jenkins Typewriter Syndicate in the early 1890s and in January

1894 the Waverley Typewriter Limited was registered to carry on business with

offices at the Mansion House Chambers, London, a plant at 51-53 Handforth Road,

Clapham, and branches in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Cardiff. It acquired

the rights to patents (1889 to 1892), plant, assets, property and premises of

the Higgins and Jenkins Typewriter Syndicate. Higgins was manager on a £600

annual salary. Nominal capital was £25,000 in £5 shares, but in September 1896

it was increased to £75,000 with another 10,000 £5 shares. But only 6917 shares

were issued in all, and Higgins blamed the failure of the company on

insufficient capital. He wanted the concern sold en bloc rather than broken up. The Manchester Guardian reported,

“Had the company gone on longer the machines would have become better known and

the value of the patents would have increased accordingly. The typewriter was a

success commercially and it would be a great pity to separate machinery and

effects for the purposes realisation [of debts]”.

Mares said the Waverley was “a magnificent piece of work”. With its differential spacing, it “produced work bearing a very strong resemblance to ordinary printing.” When D’Esterre died in France in early August 1914, he left a large fortune of £50,584 7 shillings and one penny, a small portion of which could easily have kept the Waverley going.

AND FINALLY. THE WEBSTER

WEBSTER: The

Webster typewriter was patented and the company registered with a trade name in

December 1894. The previous month Bootle, Liverpool timber merchant Joseph

March Webster (1851-1907) patented the

machine in Canada. Mares admitted to

having no details of the machine, but we can see from the Canadian patent

drawings what Webster had in mind. He was seeking simplicity and efficiency

(who wasn’t?) with comparatively few keys, which makes it sound a bit like the

Gardner. Adler called it the “Webster Miniature” and said it was “fanciful” and

an “ambitious project” dating to 1898. He said it was a tiny visible portable

writer with a universal four-bank keyboard and special keys which printed

selected phrases, such as “Yours very faithfully” and “Yours truly” with a

single depression. It was 8in by 6in by 2in high. Adler says it was not made.

FOOTNOTE: In

almost all cases when typewriter companies produced a prospectus, the “go-to”

man for references was Michael Holroyd Smith (above, 1847-1932), a consultant who was

a pioneer in electrical and motor car engineering and was considered “a creative genius”.

1 comment:

Fascinating, thanks.

The Webster looks very peculiar indeed.

Post a Comment