OUT, DAMNED TYPEWRITERS

Frederick Wilbert O'Green (1921-1998, real family name Ogren), was president of Litton Industries when the company decided to sell its typewriter division to Volkswagen in 1979. The New York Times said in its obituary for O'Green that he "led Litton Industries in the 1970s and 1980s, first as president and then as chairman ... [He] refocused Litton - a takeover star of the 1960s and a Wall Street disappointment in the early 1970s - from a sprawling conglomerate with 100 divisions to one that concentrated on defense-industry electronics. Three-quarters of the company's business now is in defense contracting, but its shipbuilding, electronics and computer technology units have broadened into commercial markets."

The search for the story

behind the Imperial Caravan (see last post) has taken me down many pathways

these past two days, and ultimately led me to the real reason Litton Industries

pulled out of the typewriter business – an event, exactly 40 years ago, which

many believe marked the death of manual portable typewriters (modern, small-scale

Chinese manufacturing aside).

Litton

brought a stop to the production of manual portable typewriters in Nuremberg in

Germany in 1979 because of the Fall of the Shah of Iran.

Mohammad

Reza Pahlavi (above, 1919-1980), the last Shah of Iran (from 1941) was overthrown in

the early days of the Islamic Revolution. Crowned Shahanshah (“King of Kings”)

on October 26, 1967, he was the last monarch of the House of Pahlavi. But he was

forced to flee Iran on January 16, 1979.

Heavens above! No more typewriters! The Shah swears in Bakhtiar.

On

February 11 control of what was once known as Persia fell to the man the Shah

had, in a compromise, appointed Prime Minister, Shapour Bakhtiar (1914-1991). One

of the first things Bakhtiar did during his mere 36 days in charge was to

inform the United States Government that he was cancelling the Shah’s $1.35

billion order for four Spruance Class destroyers at $543 million apiece. The

building of these ships was contracted by the Shah with the US Government and

subcontracted to the Litton-Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi.

A Spruance-Class destroyer.

By

mid-February 1979, Beverly Hills-based Litton Industries suddenly found itself

staring down the barrel of a $2 billion loss (notwithstanding the fact the US

Government would have had to pay it a $200 million cancellation fee). Litton started

looking around for ways to cut the impending costs. And the first bit of

“expendable” luggage it found was its ownership of the Royal, Adler, Triumph

and Imperial typewriter brands, plus the remaining Triumph-Adler factory in Nuremberg.

The Litton offering was seized upon locally, as it were, by German car

manufacturer Volkswagen.

By

1973 Volkswagen was in serious financial trouble itself. Its Type 3 and Type 4

models had sold in much smaller numbers than the Beetle and the NSU-based K70 had

also failed to woo buyers. Beetle sales had started to decline rapidly in the European

and North American markets. VW was looking to diversify, including into the

office electronic machines sector. It had already invested in a short-lived British-based

organisation called OEM, taking an 11 per cent interest.

Triumphwerke Nuremberg AG in 1955.

On

March 9, 1979, Litton agreed to sell for $26 million a controlling 55 per cent

share of Triumphwerke Nuremberg AG, described then as a typewriter and

electronic office equipment concern, to Volkswagenwerk AG. Litton retained a 19

per cent stake in the plant, down from its previous 85 per cent holding, while defence

equipment company Diehl GMBH got 25 per cent in the new arrangement. Litton said

it believed Triumph-Adler was badly in need of a large cash injection. And a

decline in the value of the US dollar had made it too expensive for Litton

itself to furnish the fresh capital, so Triumph-Adler could compete on level footing

in an expanding electronic typewriter market. It was made clear that this deal

was all about electronics, not manual typewriters. Litton was also hoping for

other joint projects with VW. Triumph-Adler’s equity rose to $43.7 million from

$24.8 million.

It

was a big step for Litton, which had reaped more than $500 million in sales

from the West German typewriter concern in the fiscal year to July 31, 1978,

13.5 per cent of Litton’s total sales ($3.7 billion) from the company’s

multitude of divisions. In spite of these typewriter sales, Litton had suffered

a net loss of $91 million, having fallen behind on its shipbuilding contracts

and being forced to make a $173 million one-off dispute settlement. The

Triumph-Adler sale to VW would cover more than 19 per cent of Litton’s potential

loss from the collapse of the Imperial Iranian Navy ship subcontract. As it

turned out, Litton made record earnings of $189 million and sales of $4.1

billion in the fiscal year ending on July 31, 1979.

Give Litton the money! John C. Stennis (right).

How

it managed to do this was quite simple. It leaned on the US Government, and in

particular on John Cornelius Stennis (1901-1995), who just happened to be

Mississippi’s senior senator and “the most influential overseer of defence

spending”. Happily – for Litton – Stennis was chairman of both the Senate Armed

Services Committee and the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defence, both

of which authorised purchase of the four ships (through President Jimmy

Carter’s supplemental request for the Pentagon). Litton had asked to be bailed

out and Stennis, standing up for Mississippi’s economy, succeeded in doing just

that, even though the four ships were well and truly surplus to US naval needs

– it already had 12 of them (the entire class comprised 31). Indeed, the US Navy

had already told Stennis’s armed services committee the ships were “obsolete

for American needs”. They originally had a air-defence missile system called

TARTAR, which had become outdated by American technology and Soviet defences.

Outmoded, like a typewriter?

Nonetheless,

Litton still got its $1.35 billion, on top of the $26 million for the Nuremberg

typewriter works. Incredibly, Stennis, with a little help from Edmund Muskie,

had convinced the government that if had to “buy back” the four destroyers it

would cost US taxpayers $2 billion. Little wonder US Defense Secretary Harold

Brown the next year repeatedly complained to Stennis that the House of

Representatives had added $7.5 billion in new programs and deleted $5 billion

in administration programs for a net increase of $2.5 billion. Brown urged Stennis’

Appropriations Subcommittee to approve the administration's budget. Instead it

approved $161 billion, $6 billion more than the administration proposal and

$3.5 million more than approved in the House. Meanwhile, typewriter-less Litton

laughed all the way to the bank.

Outrageous! Donald W. Riegle Jr (then).

Stennis’

fellow Democrat, Michigan Senator Donald Wayne Riegle Jr (1938-), sitting on

the Senate Budget Committee, called the Litton bail-out “outrageous”, as a

“classic masquerade” and an embarrassment to the administration. Riegle

suggested some of the money could go toward senior citizen lunches, where

presumably old folk could sit around talking about the demise of typewriters.

The

four surplus ships were commissioned as Kidd-class guided missile destroyers

for the US Navy. Equipped with heavy-duty air conditioning and other features

that made them suitable in hot climates, they were used in the Middle East,

specifically the Persian Gulf, and became nicknamed as the “Ayatollah” class.

They were later decommissioned and sold to the Republic of China Navy as the

Kee Lung class.

Bring on the Typewriter Revolution!

“Ayatollah”

of course refers to the Ayatollah Khomeini (Sayyid Ruhollah Mūsavi Khomeini,

1902-1989), who in February 1979 had returned to Iran after more than 14 years

in exile, mostly in the holy Iraqi city of Najaf. Khomeini soon got rid of Shapour

Bakhtiar and appointed his own interim government. In late March a referendum

to replace the monarchy with an Islamic Republic passed with 98 per cent voting

in favour. In November Khomeini became instituted as the Supreme Leader and

officially became known as the “Leader of the Revolution”. But thanks to

Bakhtiar, it sure wasn’t a typewriter revolution, quite the opposite.

On

July 28, 1986, Volkswagen was only too happy to approach the West German Cartel

Office to get approval for an April agreement to sell 98.4 per cent of its

typewriter wing to Olivetti. For $68 million the Italian company got VW’s

holding in the Royal, Adler, Triumph and Imperial brand names, plus the

Nuremberg factory, by then fully converted to making electronic typewriters.

Production of manual portables had ceased with the 1979 Litton deal, and VW had

been losing vast amounts from its electronic typewriters, grabbing just 30 per

cent of the West German market in competition with IBM, Canon, Siemens and

Brother. Triumph-Adler’s market share put it marginally ahead of Olympia in

domestic trading, with Olivetti and IBM having 10 per cent each. In the exchange,

VW got a 5 per cent stake in Olivetti for $280 million.

Eighteen

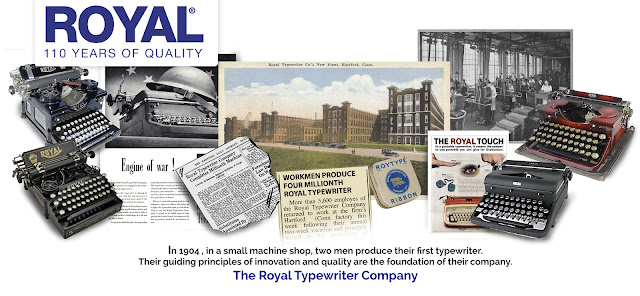

years later, in September 2004, Royal became a private American company again. It’s now known as Royal

Consumer Information Products Inc of Bridgewater, New Jersey. Among many other

things, it sells rubbishy Chinese-made manual portable typewriters, as well as

Adler and Olivetti supplies. But nothing from Imperial!

Almost 40 years on, manual portable typewriters are still being used in Tehran. A man sits on the street and uses a Brother typewriter to write court documents for customers outside the Grand Bazaar.

*A very special thanks to Richard Amery (with his 1975 Imperial Caravan) and Ted Munk

(with his extensive serial number database) for egging me on to complete the

story of the Royal, Imperial, Adler and Triumph brand names. Since the revision

of Wilf Beeching’s book we’ve known that Olivetti had finished up with these four brands, but the events which led to all that happening remained shrouded in

mystery.

3 comments:

Outstanding journalism, Robert. I have more than a passing interest in this tale because, as a young man enlisted in the US Navy, I can clearly remember being called back from liberty while on a port call in Subic Bay, late December 1978, where upon our ship, the USS Constellation, made a hurried transit of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean to remain on station in the Arabian Sea, to monitor the fall of the Shah's regime and the goings on of the new Islamic government of Iran. Little would I know that, decades later, the first typewriter I would acquire in my newfound interest would be a Royal Mercury, marketed by Litton Industries.

~Joe Van Cleave

Whoo! Talk about egging on - between your research and Polt & Obley's examinations of the brand-new Royal "Classic", we've managed to add 4 new model sections to the Royal age list (probably 5, assuming I can figure out where exactly the "Roytype by Royal" variations fit into the mid-late Oughts - I pretty much know it has to fit somewhere between 2004 when Royal became a US Company again and 2011, when Shanghai Weilv started producing the first "Scrittore" models).

Also figured out that *most* of the Royal-branded Shanghai Weilv's use a datecoded serial number at least since the Scrittore II, I haven't found any serial number for the first Scrittore, and the Roytypes *do not* use the datecode.

I'm feeling pretty good about the possibility that we might be able to finally produce a complete accounting of *all* Royal manual machines made from the beginning to the present time. That'll be very satisfying. :D

Fine work Robert. Your research is excellent.

Post a Comment