Each anniversary of D-Day, I’m reminded of A.J. Liebling, the more so since having had the extreme good fortune to find in a cut-price bin at the National Library in Canberra a few years ago a fabulous New Yorker collection called The 40s: The Story of a Decade. This included a couple of particularly brilliant Liebling articles written for The New Yorker, one about Paris immediately before its fall to the Nazis, the other about his landing at Normandy on Tuesday, June 6, 1944.

Liebling pulled some strings to get aboard a large infantry landing craft designated LCIL 88, embarking from Weymouth, Dorset. Typical of the great journalist that he was, Liebling had managed to use his connections with LCIL 88’s commander, Henry K. “Bunny” Rigg, who was rowing and boating correspondent for The New Yorker. Liebling’s description of US troops descending the ramp, heading into the shallow waters and their fate beyond, titled “Cross-Channel Trip (On D-Day)”, made watching Saving Private Ryan an experience akin to seeing a Disney fantasy after a Hitchcock thriller. One felt the blood and gore in Liebling's typewritten words, one didn’t need to see it or smell it on the page.

Roger Angell, the baseball writer with the gently magic touch who died a few weeks ago, contributed a piece published in The New Yorker on the 2019 75th anniversary of D-Day. In it he said that “Liebling put himself at ease during the pause, most notably as a messmate. Liebling’s wide range of reporting often included loving passages about French cooking, but those who knew him always understood that there was more of the gourmand than of the gourmet behind this interest. In Rigg’s account, Liebling ate, and ate steadily, for the better part of three days aboard -and, after Joe [Liebling] had been safely put ashore, Rigg and his two companions found that there was nothing left in the larder for their return trip but a box of pilot crackers.” Those who saw Wes Anderson’s wonderful bit of whimsy, The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, will recall that the character of food writer Roebuck Wright was in large part based on Liebling.

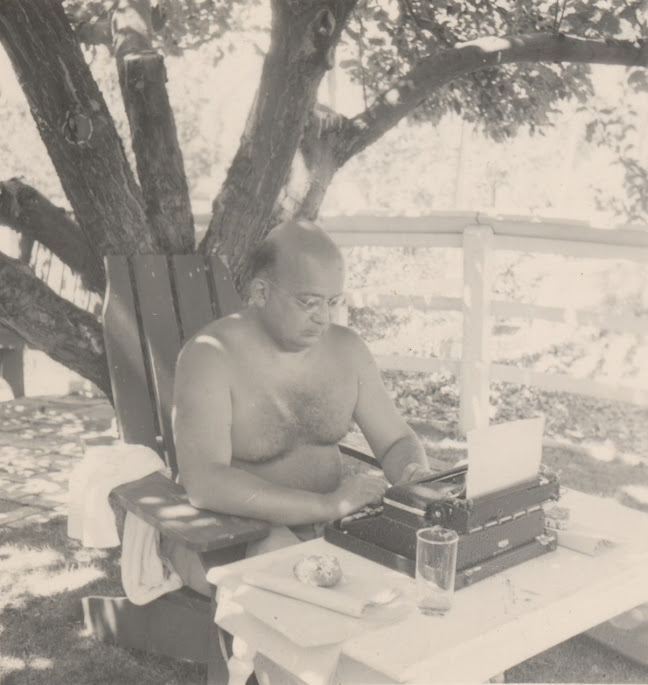

Another American journalist I think of on D-Day anniversaries is Bill Walton, above. By chance, on Sunday night, while waiting for my wife to return from Sydney by train, I happened to watch parts of a movie called Jackie. This is a 2016 biographical drama in which Natalie Portman plays Jacqueline Kennedy and the usually superb English actor Richard E. Grant is what seemed to me a rather wishy-washy Walton, an advisor to both Jackie and John F. Kennedy.

Time correspondent Walton parachuted

into Normandy with the 82nd Airborne Division. In England he had worked with Mary

Welsh, through whom, indirectly, he befriended Ernest Hemingway, who

joined Walton in Cherbourg in mid-July 1944 and with Walton covered the first

phase of the Battle of Hürtgen Forest in September-October. Hemingway saved

Walton's life during the fighting after recognising the sound of a German plane

and throwing Walton out of the jeep they were riding in, moments before it was

strafed.

After

Hemingway’s suicide in 1961, Walton used

his connections with the Kennedys to help Mary Welsh obtain a passport to Cuba

to retrieve her husband's effects and papers. In return, Walton convinced her

to deposit Hemingway’s papers at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and

Museum, of which Walton became a trustee.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment