Typewriters were still considered “newfangled” machines in 1889 when stenographer Sylvan Brooks Phillips (1866-1944), of Portland, Maine, writing for The Phonographic World, canvassed leading authors for their views on using typewriters in their work. One of the most enthusiastic replies came from Eleanor Maria Easterbrook Ames (1831-1908), who wrote under the name Eleanor Kirk, described by the New York Herald as “the most pronounced of the women’s rights women.” She used a Remington No 2 and likened the typewriter to the gift of a good angel, “a friend who is always ready and invariably correct … There is something irresistibly fascinating about this labor-saving apparatus of mine. The typewriter is one of my enthusiasms, and my delight and gratitude will last as long as the brain can plan and the hands can execute.” She praised the typewriter for its compactness, reliability and tidy work, which she said “raises [the typewriter] to the realm of the artistic”.

The Phonographic

World was a magazine started by

Kenosha, Wisconsin-born Enoch Newton Miner (1854-1923) in New York City in 1885,

just 11 years after the typewriter first appeared on the market. Miner was a

shorthand teacher before he became an editor and publisher, having been taught shorthand

in Cincinnati by Elias Longley (1823-1899), who himself had learned phonography

in Cincinnati, from Andrews & Boyle’s class book. Longley had started Phonetic

Magazine in July 1848 and was the husband of eight-finger typing pioneer

Margaret Longley (1830-1912). Miner moved to New York City soon after the

advent of the typewriter and started a magazine called Phonetic Educator.

It didn’t last long, but Miner’s second venture, The Phonographic World

continued under his ownership from 1885 until 1912. In the latter year he sold

the magazine and entered the business college line of work.

In its March 1889 edition, The Phonographic World started a series written by Phillips and called “How Authors Write”, which in particular elicited views on the use of the typewriter. Two identified their typewriter as a Remington No 2, one a Hammond and another a Caligraph. Here are the writers the magazine approached for its first installment:

Robert Jones Burdette (1844-1914) was a Greensboro, Pennsylvania-born humorist. In 1869 he became night editor of the Peoria Daily Transcript. He joined the staff of the Burlington Hawkeye in 1872 and his humorous paragraphs were soon being quoted in newspapers throughout the US. In 1884, he left the Hawkeye to replace Stanley Huntley as the staff humorist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

George William Curtis (1824-1892) was born in Providence, Rhode Island. He worked for the New York Tribune, Putnam's Magazine and Harper's Weekly. He was involved in the founding of the Republican Party. In 1863 he became the political editor of Harper's Weekly and contributed to Harper's Magazine.

Robert Grant (1852-1940) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. His first novel appeared in 1880.

Charles Howard Montague (1858-1889) was city editor of The Boston Globe when he died of typhoid fever aged just 31. His contribution to The Phonographic World had appeared eight months earlier. He was born in Greenfield, Massachusetts, and had a story published by the Cambridge Tribune when he was still at school. He started his journalism career at the Tribune after graduating, later moving to the Somerville Journal and the Boston Traveller. He joined the Globe in December 1880, becoming city editor in 1886. Montague wrote several clever novels which were serialised in US newspapers.

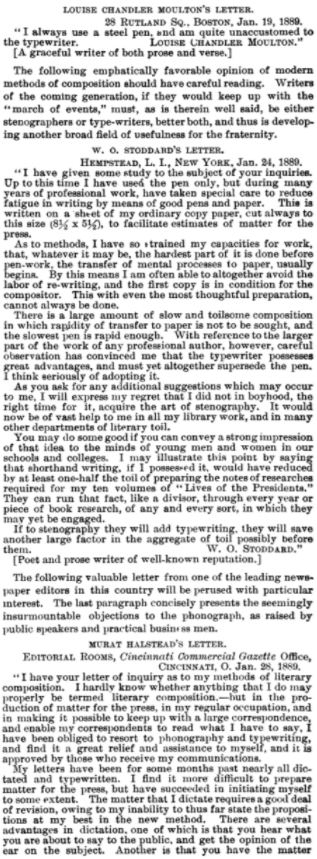

Louise Chandler Moulton (1835-1908) was a poet, story-writer and critic born in Pomfret, Connecticut. He contributed to Harper's Magazine, The Atlantic, The Galaxy and Scribner's.

Murat Halstead (1829-1908) was a newspaper editor and magazine writer, and a war correspondent during three wars. Halstead was born at Paddy's Run (now Shandon), Ohio, and begun contributing to newspapers when he was 18, writing for The Hamilton Intelligencer and The Roseville Democrat. While a student near Cincinnati he contributed to the Commercial and the Gazette. After leaving college, he became connected with the Cincinnati Atlas, and then with the Enquirer. He afterward established a Sunday newspaper in Cincinnati and worked on the Columbian and Great West, a weekly. He became news editor on the Commercial. The Cincinnati Gazette was consolidated with his paper in 1883. In 1890 he moved to Brooklyn, where he edited the Standard Union. He spent his later years writing books, mainly biographies, and contributing articles to magazines. He died in Cincinnati.

Frank Richard Stockton (1834-1902) was a writer and humorist. He was born in Philadelphia and moved back there in 1867 to write for a newspaper founded by his brother. He was also an editor for Hearth and Home magazine. Stockton's work of science fiction, The Great War Syndicate, describes a late 19th century British-American war in which an American syndicate made up of some of the country's richest men and ablest scientists conducts the war on behalf of the US. The Syndicate quickly wins this nearly bloodless war by repeatedly demonstrating an overwhelming technological superiority.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850-1919) was an author and poet. Her works include Poems of Passion and Solitude, which contains the lines “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone.” She was born on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, and had her first poem published when she was 13. Her poem “The Way of the World” was first published in The New York Sun in 1883.

Eleanor Maria Easterbrook Ames (1831-1908) was known by her pen name, Eleanor Kirk. She wrote a number of books and published a magazine entitled Eleanor Kirk's Idea. She was also a regular contributor to The Revolution and Packard's Monthly. “Nellie” Easterbrook was born in Warren, Rhode Island, and later moved to Brooklyn. In 1870, the New York Herald said she was “the most pronounced of the women’s rights women.”

Mary Virginia Terhune (née Hawes, 1830-1922) was known by her penname Marion Harland, a prolific and bestselling author in both fiction and non-fiction genres. Born in Dennisville, Virginia, she began her career writing articles at the age of 14. In 1871 she wrote Common Sense in the Household: A Manual of Practical Housewifery, a cookbook and domestic guide that was a huge bestseller, eventually selling more than one million copies over several editions. After breaking her wrist, Terhune learned to use a typewriter.

James Parton (1822-1891) was born in Canterbury in England. He was a biographer who wrote books on the lives of Horace Greeley, Aaron Burr, Andrew Jackson, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Voltaire, and “Eminent Women of the Age”.

William Henry Rideing (1853-1918) was born in Liverpool, England, but raised in Chicago. At 17 he worked for the Springfield, Massachusetts Republican. In 1874 he gave up newspaper work to devote himself entirely to literature and magazine writing. In 1878 he served as special correspondent with the Wheeler Survey expedition in Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, California, and Arizona. From 1881 Rideing edited Dramatic Notes in London, England. On his return to America he again entered journalism, in Boston.

Edward Eggleston (1837-1902) was an historian and novelist. He was born in Vevay, Indiana, and ordained as a Methodist minister in 1856. He wrote a number of tales, some of which, especially the “Hoosier” series, attracted much attention.

Eleanor Kirk

In its March 1889 edition, The Phonographic World started a series written by Phillips and called “How Authors Write”, which in particular elicited views on the use of the typewriter. Two identified their typewriter as a Remington No 2, one a Hammond and another a Caligraph. Here are the writers the magazine approached for its first installment:

Robert Jones Burdette (1844-1914) was a Greensboro, Pennsylvania-born humorist. In 1869 he became night editor of the Peoria Daily Transcript. He joined the staff of the Burlington Hawkeye in 1872 and his humorous paragraphs were soon being quoted in newspapers throughout the US. In 1884, he left the Hawkeye to replace Stanley Huntley as the staff humorist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

George William Curtis (1824-1892) was born in Providence, Rhode Island. He worked for the New York Tribune, Putnam's Magazine and Harper's Weekly. He was involved in the founding of the Republican Party. In 1863 he became the political editor of Harper's Weekly and contributed to Harper's Magazine.

Robert Grant (1852-1940) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. His first novel appeared in 1880.

Charles Howard Montague (1858-1889) was city editor of The Boston Globe when he died of typhoid fever aged just 31. His contribution to The Phonographic World had appeared eight months earlier. He was born in Greenfield, Massachusetts, and had a story published by the Cambridge Tribune when he was still at school. He started his journalism career at the Tribune after graduating, later moving to the Somerville Journal and the Boston Traveller. He joined the Globe in December 1880, becoming city editor in 1886. Montague wrote several clever novels which were serialised in US newspapers.

Louise Chandler Moulton (1835-1908) was a poet, story-writer and critic born in Pomfret, Connecticut. He contributed to Harper's Magazine, The Atlantic, The Galaxy and Scribner's.

William Osborn Stoddard (1835-1925) was an author, inventor and assistant secretary to Abraham Lincoln during Lincoln’s first term. He was born at Homer, New York, and started work in 1857 at the Daily Ledger in Chicago. The next year he was editor and proprietor of the Central Illinois Gazette in Champaign, Illinois. Stoddard first published work in 1869 and wrote both poetry and fiction, ultimately producing more than 100 books.

Murat Halstead (1829-1908) was a newspaper editor and magazine writer, and a war correspondent during three wars. Halstead was born at Paddy's Run (now Shandon), Ohio, and begun contributing to newspapers when he was 18, writing for The Hamilton Intelligencer and The Roseville Democrat. While a student near Cincinnati he contributed to the Commercial and the Gazette. After leaving college, he became connected with the Cincinnati Atlas, and then with the Enquirer. He afterward established a Sunday newspaper in Cincinnati and worked on the Columbian and Great West, a weekly. He became news editor on the Commercial. The Cincinnati Gazette was consolidated with his paper in 1883. In 1890 he moved to Brooklyn, where he edited the Standard Union. He spent his later years writing books, mainly biographies, and contributing articles to magazines. He died in Cincinnati.

Frank Richard Stockton (1834-1902) was a writer and humorist. He was born in Philadelphia and moved back there in 1867 to write for a newspaper founded by his brother. He was also an editor for Hearth and Home magazine. Stockton's work of science fiction, The Great War Syndicate, describes a late 19th century British-American war in which an American syndicate made up of some of the country's richest men and ablest scientists conducts the war on behalf of the US. The Syndicate quickly wins this nearly bloodless war by repeatedly demonstrating an overwhelming technological superiority.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850-1919) was an author and poet. Her works include Poems of Passion and Solitude, which contains the lines “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; weep, and you weep alone.” She was born on a farm in Johnstown, Wisconsin, and had her first poem published when she was 13. Her poem “The Way of the World” was first published in The New York Sun in 1883.

Eleanor Maria Easterbrook Ames (1831-1908) was known by her pen name, Eleanor Kirk. She wrote a number of books and published a magazine entitled Eleanor Kirk's Idea. She was also a regular contributor to The Revolution and Packard's Monthly. “Nellie” Easterbrook was born in Warren, Rhode Island, and later moved to Brooklyn. In 1870, the New York Herald said she was “the most pronounced of the women’s rights women.”

Mary Virginia Terhune (née Hawes, 1830-1922) was known by her penname Marion Harland, a prolific and bestselling author in both fiction and non-fiction genres. Born in Dennisville, Virginia, she began her career writing articles at the age of 14. In 1871 she wrote Common Sense in the Household: A Manual of Practical Housewifery, a cookbook and domestic guide that was a huge bestseller, eventually selling more than one million copies over several editions. After breaking her wrist, Terhune learned to use a typewriter.

James Parton (1822-1891) was born in Canterbury in England. He was a biographer who wrote books on the lives of Horace Greeley, Aaron Burr, Andrew Jackson, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Voltaire, and “Eminent Women of the Age”.

William Henry Rideing (1853-1918) was born in Liverpool, England, but raised in Chicago. At 17 he worked for the Springfield, Massachusetts Republican. In 1874 he gave up newspaper work to devote himself entirely to literature and magazine writing. In 1878 he served as special correspondent with the Wheeler Survey expedition in Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, California, and Arizona. From 1881 Rideing edited Dramatic Notes in London, England. On his return to America he again entered journalism, in Boston.

Edward Eggleston (1837-1902) was an historian and novelist. He was born in Vevay, Indiana, and ordained as a Methodist minister in 1856. He wrote a number of tales, some of which, especially the “Hoosier” series, attracted much attention.

2 comments:

Fascinating and historic. Thanks for making this information available!

I don't think I could ever "write" by dictating to someone. I need intimacy between myself and my pen or keyboard.

Thanks for all the wonderful information on writers and typewriters. I found there were several similarities with changing to a PC. The typewriter though has none of the distractions, and many more benefits.

I'm not a writer, but I can't imagine dictating an article or a book to a stenographer.

And the noise of a typewriter I find relaxing and inspiring rather than distracting.

Post a Comment