AUGUST 24

On this day in 1921, 90 years ago today, Max Helm, of Niederschönhausen, outside Berlin, filed for a US patent for an improvement to the shift key arrangement on the great Mignon typewriter.This gives us an excuse, if ever one were needed, to look at one of the special favourites of all typewriter collectors.

Helm had already filed applications in Germany, Hungary, Austria, France, Czechoslovakia and England for the same design.

Whether the original US patent for the Mignon, issued to Friedrich Heinrich Philipp Franz von Hefner-Alteneck on March 2, 1909, was still in force is questionable. Hefner-Alteneck had died more than five years before his US patent was granted.

Nonetheless, Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) was very much still making the Mignon in 1921, and continued to do so until 1934, by which time some 363,000 of them had been produced.

As Paul Robert at the Virtual Typewriter Museum in Amsterdam says on his website, the Mignon remains the “mother of all index typewriters”.

(Images of Mignons here include those from the Richard Polt,

Paul Robert, Wim van Rompuy and Martin Howard collections)

The introduction to Hefner-Alteneck’s US patent application of July 7, 1902 (above), reads rather grandly: It states: “Be it known that I, Friedrich Hefner-Alteneck, Ph D, a subject of the King of Bavaria, and resident of No 10 Hildebrandt'sche Privatstrasse, Berlin, in the Kingdom of Prussia and Empire of Germany, have invented certain new and useful improvements in Type-Writers, of which the following is a specification:“This invention relates to a typewriter having a typeroller but without a keyboard, which differs from known typewriters of the type referred to in that the adjustment or movement of the type as also the impression or printing of the same, requires only a very slight movement of the hand.”

According to an article which appears on Richard Polt’s The Classic Typewriter Page, (http://site.xavier.edu/polt/typewriters/mignon.html) written by Berthold Kerschbaumer and translated by Richard, the Mignon was developed “on the basis of a patent by Louis Sell of Berlin (No 149308 of December 22, 1901), and the first 50 machines were produced”.

However, I can find no reference to Sell elsewhere, and his name does not appear in either Hefner-Alteneck’s nor Helm’s patent applications. Other histories credit the Mignon to Hefner-Alteneck, and it is true that at least the AEG Mignon was his design.

Helm referred to Hefner-Alteneck in his 1921 application (above), saying it related “to a type cylinder typewriter of the kind described and illustrated in the specification of Letters Patent of the United States 914,273 granted to Friedrich von Hefner-Alteneck and which is provided with a space divided according to the letters of the alphabet (henceforward called the "alphabet table") and an indicator, in which either the indicator and the writing-key are connected, or in which the indicator and the writing-key are operated separately.”

Helm wrote of his improvement that the machine “would be manipulated in the same manner as formerly, except that when a character is struck one or other of [several] writing keys is chosen, thus rendering it possible to write 'large and small characters' without employing a special shift-key”.

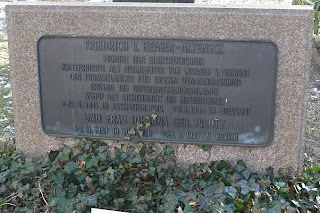

Friedrich Heinrich Philipp Franz von Hefner-Alteneck was born on April 27, 1845, in Aschaffenburg. His father, Jakob Heinrich von Hefner-Alteneck, was an art historian and director of the Bavarian national museum.

Friedrich attended a technical university in Munich and a polytechnic in Zurich. After working in Munich, Hefner-Alteneck joined Siemens and Halske AG in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

Siemens had been founded in 1847 as Telegraphen Bau-Anstalt von Siemens and Halske by Ernst Werner von Siemens and Johann Georg Halske. The company made Charles Wheatstone's 1837 electrical telegraphs, but its fortunes rose on the back of Werner von Siemens' 1867 electrical generator (dynamo).

Siemens (above) exhibited the dynamo at the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris, and this is generally accepted as the dawning of the electric power age.

The young Hefner-Alteneck was keen to become involved in the development and applied to join Siemens as a draughtsman. He was employed in the company’s design engineering department and soon became director. He contributed significantly to the 7000 mile-long Indo-European (London to Calcutta) telegraph line in 1870.

In 1872, at 27, Hefner-Alteneck became assistant to Carl Fischer as general technical manager. He developed the dynamo, making it more durable and therefore more marketable. It is still used in basically the same form in electrical machines today.

Another of Hefner-Altenick’s achievements in this period was to develop Wheatstone's machine into a Morse typewriter.

Hefner-Alterneck’s differential arc lamb was first demonstrated at the Berlin Industrial Exhibition in 1879. It was used at the Berlin Imperial Passage (intersection of Unter den Linden-Friedrichstraße), showing that it could light streets brightly, safely and economically.

This led to competition with gas lighting, and the need for a suitable unit to test the brightness of the two sources. Hefner-Alteneck suggested a flame as comparison, and this is where he was to win his most lasting fame: through his 1884 invention of a laboratory light standard, the Hefner lamp.

From 1880 to 1890 Hefner-Alteneck was Siemens’ director at Charlottenburg. The Hefner lamp provided the measure of precise luminous intensity used in Germany, Austria and Scandinavia from 1890 to 1942. The measure was called the Hefnerkerze (HK). The Hefnerkerze was superseded in the 1940s by the modern SI unit, the candela.

Werner von Siemens retired in 1889 and Hefner-Alteneck also left the company soon after, accepting a seat on the board at Siemens’ rival Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), formed in 1887 by Emil Rathenau.

At AEG, Hefner-Alteneck first worked on an electric keyboard typewriter, and six prototypes were made.

Eighteen months after he had applied for his US patent for the Mignon, Hefner-Alteneck died, aged 58, on January 6, 1904, in Biesdorf, outside Berlin. The US patent was issued more than five years after his death.

Berthold Kerschbaumer’s article on Richard Polt’s The Classic Typewriter Page says the AEG board could not be persuaded that Hefner-Alteneck’s electric machine was ready for the market, but saw real sales potential only for the Mignon.

“Thus, the machine which had been conceived ‘only’ as a secondary project was put into further production…”

An AEG subsidiary, Union Schreibmaschinen-Gesellschaft, was founded and started to make the Mignon in 1904.

In 1905 the improved Model 2 added a ribbon instead of an ink roller, and the space key and printing key were moved to the right of the index. “This basic arrangement was altered only slightly in subsequent models,” writes Berthold.

The rectangular index includes 84 characters in seven rows. The lowercase letters are arranged on the right, the capitals on the left, and special characters on the perimeter.

The arrangement of the characters follows the order of their frequency, starting with the centre of the index.

The Mignon, or slight variations on its general theme, appeared in many other forms, such as the Plurotyp, Simplex (Britain), Genia, Yu Ess, Stella, Eclipse, Heady and Tip-Tip (Czechoslovakia, 1936)

In 1898, the Anderson County, Indian, newspaper declared: “William Roland, ex-county treasurer of Madison County, and Earl Reeve, son-in-law of John W. Lovett, of Anderson, associated with William Shirk, the inventor, will have a new typewriter machine on the market in three months.”

I somehow don’t think this bold statement proved to be accurate. Nonetheless, on this day in 1897, William Snyder Shirk, of Anderson, Indiana, did receive a patent for a typewheel typewriter.

Shirk declared in his application (filed on August 15,1896) that his typewriter had “for its object to provide a compact, efficient, and comparatively inexpensive mechanism of that class wherein the type are carried by a typewheel or its equivalent, which is adjusted to bring the proper type-face into the printing-plane in order to secure the impression of the proper character.”

William Snyder Shirk was born to Christian Shirk and Sarah Stoner Shirk in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on December 28, 1852. He was married very late in life, aged 64, to Grace Call, 21 years his junior, in Anderson in 1917.

Regardless of the Anderson newspaper’s confident 1898 prediction about his machine, Shirk didn’t subsequently shirk on typewriters, and in July 1901 patented a ribbon-feed mechanism.

This consisted of a frame, “which may be of any construction suitable for the machine with which it is to operate”, carrying two ribbon spools … which spools have ratchets each adapted to engage a pawl which turns the spool as the frame oscillates …”

On this day in 1886, John Thomas Underwood and his bother Frederick Wills Underwood patented the carbon paper upon which (along with ribbons) the Underwood company was sustained until Remington, almost fatally, decided to make its own carbon paper and typewriter ribbons, in 1893. The Underwoods had given away all the secrets to their carbon paper making in their 1886 patent.

John Thomas, then a mere 24, and Frederick Wills Underwood, 23, had taken over the running of the family company when their father, John Underwood senior, died in 1881. Frederick himself died, in 1891, aged just 33.

The ingredients for the paper were part of a patent originally applied for in 1880, when John senior was still alive.

The Underwood brothers referred to the carbon paper as a “Reproducing-surface for typewriting and manifolding”.

The process, using alkaline and acid, was described thus:

Take one pound of extract of logwood [haematoxylin, from Brazil wood, sapan wood, peach-wood or madder] and dissolve in one gallon of water, then add to the solution one pound of soda and one pound of mineral salt, using one of the salts of iron or copper, preferably sulphate of copper. The mixture thus obtained is then placed in a filter. After the solution has been filtered the precipitate is removed from the device employed and dried. To every two pounds of precipitate thus obtained we add one pound of oil and one pound of wax, and then grind the mixture in a warm state in a grinding mill. The heated mixture thus obtained is then applied to tissue-paper or other suitable paper or fabric by means of a sponge or other suitable transferring device.

“The paper or fabric to which our improved surface is to be applied is placed upon a heated table, by preference formed of iron, and heated by steam; but this may be varied.”

For the Underwood company history, see http://oztypewriter.blogspot.com/2011/07/on-this-day-in-typewriter-history-xliv.html

3 comments:

You persist in making my website obsolete. ;)

The Mignon is a great invention and worthy of a "This Day" feature.

Bravo! Very much enjoyed reading this.

I've just come to the section in Beeching's "Century of the Typewriter" on Mignon, and after reading his abbreviated material and then reading yours, I must say you add a great deal more detail and interesting asides & trivia than I've been getting from the books.

Thanks so much for shedding such a wide-ranging light on the histories of these machines! (:

Post a Comment