THE FIRST TYPECAST

FROM CINCINNATI?

and the

NASTY TRUTH OF THE

NICKERSON TYPEWRITER

scrupulous was the

- Nickerson Typewriter Company secretary

James Kennedy Anderson, 1915

What was it with men of the cloth and typewriters? Idle hands? Or divine intervention and inspiration? Whatever, it seems an inordinate number of abbots, priests, padres, reverends, vicars and sundry church ministers tried to invent typewriters from the mid-19th century to the early part of the 20th century. At least one succeeded.

The list of those who failed includes the Reverend John S. Martin of the sweetly named Cherry Fork, Ohio.

It was on this day in 1882 that the Reverend Mr Martin, still a young man but not long for this earth, was issued with a patent for what typewriter historian Michael Adler described as “a circular index machine printing on a flat paper table”.

When the Reverend Martin sent his application off to his patent attorney, the engraving of what Martin envisaged as his typewriter was added and it showed a letter being typed and datelined “Cincinnati, O, March ... J. Smith Esq ... Dear Sir”. Is this the first example of typecasting from Cincinnati?

The ambitious reverend listed five objectives for his typewriter:

1. Having the letters of the alphabet, figures, points etc [there’s that Cincinnati connection again!], cast on the lower face of the disk, the said letters and figures being in relief and homogeneous with the disk. Centrally is an arbor or spindle, which projects vertically through and is journaled in the forward end of a vibrating arm. The upper end of the arbor or spindle is provided with a hinged arm having a downturned end or point, which is provided with a V-shaped fork. To this arm is attached the lower end of the stylus or holder, which in writing is grasped by the hand.

2. A table directly beneath this elastic type-disk, with an ink-pad having an aperture or opening at one side slightly larger than the face of one of the letters or characters on the disk, so that the letter-paper beneath the ink-pad will receive the impression of the letter or character which appears at the aperture in the ink-pad.

3. An upper stationary face of the vibrating plate to which the revolving type-disk is journaled provided with letters, characters, or figures in a circle to correspond with the letters and characters on the typedisk beneath, and each letter is provided with a radiating bar, so that the V-forked arm of the disk-arbor may be placed on said bars, as the different characters or letters desired are successively selected by the operator.

4. A vibrating arm having at its rear end a retractile spring, and provided on the side with an adjustable latch for feeding the paper when the machine is in motion.

5. A rack-bar sliding in a groove in the table beneath the pa per, with which the latch engages, having at the opposite end a transverse bar secured thereto, said bar being provided with a notched or serrated edge, to indicate the distance of the lines on the sheet in writing; and, further, in having a sliding clasp secured to the transverse bar for holding the paper.

At the time of applying for his patent, John S. Martin was the United Presbyterian Church minister in Cherry Fork. He had been installed in October 1877 and, according to church records, “filled [the position] with marked ability until the date of his death, April 6, 1889. The Reverend Martin received a salary of $1000.”

Martin was just 37 when he died – and 31 when he designed his typewriter. He was born in Illinois in 1851.

Adler suggests the first working typewriter ever made was put together by one Reverend William Creed in London as far back as 1747. It was the Melograph (below), an apparatus to be attached to a harpsichord or clavichord “whereby every note played was committed to paper”. Adler quoted from a letter written by one John Freke and published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, so that Creed’s invention should not be “lost to Mankind”. Freke called the clergyman “a man well acquainted with all kinds of mathematical Knowledge” and “a Gentleman of very distinguished Merit and Worth”.

In 1855, a French abbot, Abbé Clément, was able to type out the names of his students. Sadly, the Abbé’s machine was promptly destroyed by a Second Empire provincial politician called Count d’Aunay because, with it, “anyone, without even the help of a printer, could produce and distribute pamphlets not only against morality but against the Régime itself!”

In 1861, a Brazilian priest, Padre Francisco João de Alezedo, built a wooden stenographic typewriter (above). It won awards at exhibitions in Recife and Buenos Aires, after which it was selected to represent Brazil in an international exhibition in London in 1862. But it never made the trip and was not heard of again.

Then in 1865, of course, came the famous “skrivekugle”, or writing ball (above), from Danish Pastor Hans Johan Rasmus Malling Hansen (below).

The great Oliver typewriter (below) was the work of Canadian-born Methodist minister Thomas Oliver (below). The Reverend Oliver’s motivation was to build a legible means of writing and distributing his sermons in Iowa. The Oliver Typewriter Company was headquartered in Chicago.

Another typewriter company with Chicago connections was one started in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1906 by a Presbyterian minister, Charles Sparrow Nickerson.

Richard Polt drew my attention to the Nickerson back on August 21, after I had posted on a typewriter patented in 1889 by Frederic Erasmus Gladwin (born Connecticut, 1859; died 1940), who ran a typewriter supplies company in San Francisco. Gladwin’s machine operated with “a sheet of paper wrapped around the roller and [on which] the line of writing is carried circumferentially … After one line is written the next line is spaced by a longitudinal movement of the roller in the direction of its axis.” Richard Polt remarked, “In Gladwin's arrangement, you would have to cock your head sideways to read your typing; it would make more sense to arrange the axis of the platen vertically. This is just what the Nickerson Automatic did!” Richard sent me some of these images of the Nickerson.

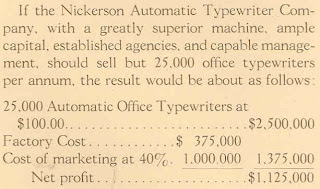

The story of how the Nickerson came to be is not only quite mysterious. Since the good Dr Nickerson, a Doctor of Divinity, was supposedly a God-fearing, scrupulous, upstanding churchman and member of decent society, and a published author on the subject of Christianity, his business dealings would appear to have risked bringing down upon him the wrath of God. More to the point, in insisting the Nickerson was his invention "and not an imitation", and an "original invention" - as the promotional material stressed - the evidence suggests he was being completely dishonest. That is, if one accepts the widely-held and published theory that the Nickerson actually started life as the Hanson typewriter. Compare the progressive designs:

Hanson patent 1899 assigned to Antonia Hansen and Ole H. Lee

Baillard patent 1902, assigned to Antonia Hanson and Ole H. Lee

Nickerson patent 1904, assigned to the Nickerson Typewriter Company

In the September 1997 issue of ETCetera (No 40) when the magazine was edited by Darryl Rehr, the back page colour gallery contained this image of a Nickerson No 3.Rehr said the machine was in the Milwaukee Public Museum collection and that it “appears to be related to another similar machine called the Hanson (below, identified in ETCetera No 49, December 1999, as the Hanson-Lee; Ole Lee's involvement is explained later).

"Both are apparently one-of-a-kind prototypes. The Nickerson’s paper is put on a vertical cylindrical frame, which moves around its axis for letter spacing and vertically for line spacing. The platen is actually a small wheel …”

That same year, Michael Adler in Antique Typewriters described a “remarkable vertical platen typewriter based upon ideas first evolved in 1899 by Walter Hanson of Milwaukee, whose frontstroke machine with its four-row keyboard which typed around, not along, the vertically-mounted platen apparently passed from the hands of the inventor upon his untimely death, to those of a Reverend Lee and eventually Nickerson.”

I have no idea where Adler obtained this information and I cannot verify it. What I can say with certainty, however, is that one Walter H. Hanson did indeed patent such a typewriter (on May 18, 1899), and it was assigned to Antonia Hanson and Ole H. Lee. It may well be so, indeed seems likely, that Walter Hanson meet an “untimely death”, but his patent is assigned – Antonia Hanson and Lee are not designated as executors of an estate. If Walter Hanson was dead when the application for the patent was made, in January 1898, he would have been very young when he passed away, and younger still when he invented his typewriter. He was born in Milwaukee in 1877. That means, at best, he was 21 when he invented this machine.

At his Virtual Typewriter Museum, Paul Robert states Walter Hanson was 21 when he died. However, Paul uses much the same information as Rehr, adding that Hanson “left his unfinished design behind. The machine was picked up by the Milwaukee reverend Charles S. Nickerson [Nickerson was never based in Milwaukee].

“Nickerson took the unfinished Hanson design and had a completely new machine built that was patented in 1909.”

Walter’s father, Peter, was dead by the time of the 1900 US census, when Walter’s mother was listed as a widow living with Lee and his family, and as Lee’s mother-in-law. However, it seems Lee was not married to the sister called Antonia, so it cannot be certain whether the assignee of Walter’s patent was his mother or his sister. If it was his sister, she was not living with her mother and Lee's family in 1900, and was still single in 1902.

Lee was also born in Norway, in January 1849, the year an 11-year-old Antonia senior migrated to the US with her family. Lee was indeed, as Adler says, a clergyman, and in 1900 he patented a typewriter in his own name in Canada.

This appears to be the so-called Hanson-Lee typewriter. In ETCetera No 49, Rehr says, "Apparently this [what he calls the Hanson-Lee typewriter] is the predecessor to the Nickerson machine ...It is said to be the invention of Walter Hanson of Milwaukee with a 'Rev. Lee', apparently the silent partner in the enterprise. The Dietz catalog says Hanson died at age 21. Lee apparently turned it over to a Rev. Nickerson for whom the later machine is named."

Yet there is no evidence, as far as I can find anyway, that the patent rights were ever handed on to Nickerson, by Lee or anyone else. What's more, by the time Lee became involved in the project, Hanson was presumably already dead by a year or two.

But what Darryl Rehr and others have missed is where the mystery truly deepens. In 1902, Edward Victor Baillard, of Brooklyn, not mentioned by Adler or Rehr, patented essentially the same design as the Hanson-Lee and Nickerson typewriters. And he assigned his patented to – Antonia Hanson and Ole H. Lee! This surely indicates the widow Mrs Hanson and the Reverend Lee gave Baillard the right to carry out further development of the Hanson design, not Nickerson.

Nickerson's second patent, 1909

Baillard states in his patent application that his design “is an improvement” on Walter Hanson’s machine, yet does not mention Hanson by name, merely citing the original patent number.How Nickerson then became involved in this, if it is the same project, is unknown, notwithstanding Adler’s claims indicating a link between Lee and Nickerson.

Did Nickerson really legally acquire the right to develop the Hanson patent, either through Baillard or Hanson’s mother and brother-in-law? If so, why did he not acknowledge the prior work of Hanson and Baillard in his own patent applications? The Nickerson Typewriter Company secretary, James Kennedy Anderson, who at first trusted Nickerson implicitly as an old friend, and thus willingly became involved in Nickerson’s typewriter project, was to live to regret having done so. It ended up costing Anderson a lot of money. The sizable investment of a woman called Mrs Gilbert was another major point of contention in the ultimately sorry saga of the Nickerson typewriter.

Anderson seems to have been right on at least one count: Nickerson never co-assigned his patents, as promised, to Anderson.

Anderson was to question Nickerson’s honesty and integrity. Indeed, it was even suggested to Anderson that Nickerson may have been guilty of criminal conduct in stealing company documents held in an office in a Masonic Temple.

Anderson was himself in time to put to Nickerson the suggestion that Nickerson may be willing to “cheat” his own company of funds, by making misleading statements. So just how upright and ethical was the Reverend Dr Nickerson? A man capable of stealing a dead man’s typewriter idea? The written evidence of Anderson might well suggest so.

When Nickerson patented his machine in 1909, there is no reference to preceding Hanson, Baillard or Lee patents. Nor is there in any of the preceding Nickerson patents, leading to his final design and dating back to 1904. The Reverend Nickerson was either being dishonest about the originality of his design, or was somehow oblivious to the Hanson-Baillard designs.

Charles Sparrow Nickerson was born on April 30, 1860, at Beverly, Ohio. He attended the Union (New York) and Lane (Cincinnati, 1884-85) theological seminaries, becoming a clergyman at Greenport, New York (1887-89), Waukesha, Wisconsin (1889-92), Racine, Wisconsin (1892-1901), and then Walnut Street, Evansville, Indiana. While he was in Evansville, he continued to assign his typewriter patents to the Nickerson Typewriter Company in Racine, Wisconsin, where the company was incorporated. In 1910 the Nickerson Automatic Typewriter Company moved its headquarters to Chicago, and the following year, with the alleged granting of overseas patents, it became known as the International Typewriter Company. Nickerson was president and J. Kennedy Anderson its secretary.

A great-grandson of Anderson, Scott Lindstrom, of Wisconsin, has been good enough to put on the web a lot of formation about the rapid rise and fall of the Nickerson typewriter. Thanks to Scott, we know that before he died in 1915, a rather bitter Anderson set out the history of the Nickerson typewriter.

This document makes it clear that in 1904 Nickerson considered the machine “his” invention [no mention of Hanson]. The first models were made in Groton, possibly by Crandall, and exhibited in Milwaukee. However “capitalists” were in short supply because of the collapse of a typewriter company in Kenosha (Sholes Visible perhaps? A.D. Meiselback Typewriter Company?). “Finally an agreement was entered into verbally with an inventor of an adding machine (which had been sold out to the Dayton concern and had a large vacant factory and excellent financial connections) to take over the patents on very satisfactory terms.”

Days later, Nickerson had a heart attack and the deal was called off. When he recovered, Nickerson took the machine to Elgin, Illinois, and got the backing of Henry G. Sawyer, who wanted to built the typewriters at his Star Manufacturing plant. Sawyer backed out and the operation moved to Racine, with models made in Chicago. But Anderson felt he had reason to begin to distrust Nickerson, wondering if important company documents had been stolen by Nickerson and saying he had “lost confidence in Dr Nickerson's sense of honour”.

Among others, a S. A. Cook, of Neenah, Wisconsin, in Lansing the Oldsmobile Company (having ended its relationship with Buick), and in Scranton a man called C. Law Watkins, all showed interest. But Watkins’s involuntary bankruptcy seemed typical of the unfortunate chain of events. The Nickerson typewriter appeared fated, doomed, and indeed it was. For a while longer it struggled on, to Rockford (a man called Roper), but by 1913 the end was nigh.

On November 30, 1914, Nickerson wrote, “The thing is utterly gone to smash … If the International Company is now alive it will live six months longer. In my opinion it is dead.”

In 1925 Nickerson published Christianity, Which Way?: A Historical Study of Changes and Achievements in the Christian Church. He died on March 24, 1942, aged 81.

Michael Adler mentions another “reverend”, Henry J. Otto, of Princeton, Indiana, in reference to typewriter-related patents issued in 1907. Adler gained this information from A Condensed History of the Writing Machine (1923), which says these were “Another instance of invention of a writing instrument by a minister …” Adler adds the line that Otto’s unrealised idea “was not of divine inspiration”. The story of the Otto typewriter is almost as intriguing as that of the Nickerson typewriter – but we won’t go there today: the Californian-born Otto wasn’t a reverend at all, he was a novelty manufacturer. So we will look at Otto some other day.

3 comments:

Another eye-opening piece of research!

Doesn't "Nickerson" seem like a perfect, Dickensian name for a man who apparently stole his typewriter design from someone else? He never dreamed that his perfidy would be discussed a century later.

I suppose there is a chance, though, that his design really was developed independently from Hanson's. The patent office apparently thought it was different enough to merit a separate patent.

I do wish that the typewriter had been built in some quantity. It's a wonderful design. If I had one, I would display it proudly and create some typecasts from Cincinnati ending "Sent from my Nickerson Automatic Typewriter."

PS: I'd never heard of the hamlet of Cherry Fork, Ohio, but I see you that Google even offers street views of it. I saw one of those Google Street View vehicles driving through my own neighborhood the other day. They're brightly marked and have a turret on them that contains the camera. There must be tens of thousands of them. -- Sorry for the digression!

I see a candidate for a Script Frenzy project in this story! So many great quotes to spice up the intriguing story.

Post a Comment