SEPTEMBER 10

THE GENESIS OF THE ROOY

Where the crusading

Joseph Louis Adhémar Borel

Borel’s patents were assigned to the Société Rooy (Etablissement Rooy Société Anonyme), a joint-stock company based in Paris. Rooy was the family name of some of the directors and stockholders of the manufacturer. The trade-mark Rooy was not, however, registered in the Tribunal du Commerce de la Seine until December 16, 1949.

In the part of his divided application which related the Rooy’s revolutionary sliding lid – allowing the Rooy to fit comfortably into a brief case - Borel used as a reference, significantly, the detachable, rigid base plate patented by Giuseppe Prezioso in 1935 for his Hermes Featherweight (below).Borel called his design an “enclosing and supporting case for portable typewriters”.

Borel also referred to a case designed by Joseph B. Holden in 1923 to snugly and safely hold the little Remington Model 1 portable. Holden’s patent brings to our attention that although this machine was originally designed by John Henry Barr, “simpler compacting mechanisms” were added by Arthur W. Smith in 1920. So perhaps this famous Rem was the result of team work, after all.

Borel made no fewer than 13 references in his application for a patent for the “type action system for portable typewriters”.

These began with a 1909 James Denny Daugherty design for a back-mounted pawl to steady and control the speed of the escapement. There were three from William Albert Dobson (1922, 1928 and 1939), all assigned to Underwood. These were for a silent key mechanism, ribbon feeding and a durable, quiet shift lock abutment. Of course, Dobson’s “trapdoor” was on the front of an Underwood standard, not under the keyboard, as on the Rooy. On the issue of sound, Swedish-born Carl Ernest Norin designed for Underwood in 1931 a segmental stop for reduced noise.

Another reference which came into play on the Rooy was a 1923 design by Charles Underwood Carpenter, of Dayton, Ohio, for a “low structure”, compact typewriter with a short depth typebar operation.

As well, Emmit Girdell Latta’s in-folding typewriter (lowering and collapsing inwards to fit into a small case), also from 1923, was viewed in designing the Rooy.

The distinctive folding line-spacing lever we have all come to love and admire was designed by Fred Fray of Paducah, Kentucky, for Underwood in 1931.

In 1936 Otto Haas, of Pieterlen, Switzerland, followed Prezioso’s Hermes Featherweight lead with another typewriter which was of “small height, most compact construction”.

The great Underwood mechanical engineer William Ferdinand Helmond in 1939 designed for all sizes of typewriter a “readily removable and replaceable” spring-motor. I wish all typewriters had such a thing! Would save so much hassle.

Interestingly, Pascher’s US patent (is it perhaps for the Groma Kolibri?) was “vested with the alien property custodian” – this, after all, was at the height of World War II.

So on to the Rooy itself …

Apparently M J Rooy had started out making a Mignon-style index typewriter called the Heady. In 1936 the company gained a production license from Underwood, and in the late 1930s and again after World War II, it produced both standard-sized and portable typewriters very much in the Underwood style. This might also account for the number of Borel references to Underwood patents.

But in 1936 Rooy’s finances were in such a bad state that employees decided to defy government laws and work a 48-hour week, to help get the company back on its feet.

Rooy survived the war years and in the late 1940s resumed producing typewriters, as well as calculating machines, apparently under license from Odhner.

Rooy’s decision to make the ultra-slim Borel typewriter may well have been inspired by the efforts of Pascher, and also by another Parisian, Maurice Etienne Julliard. In the same late-40s period, Julliard set out to make a tiny pocket typewriter “with rotary and translatory work support”. Julliard went on to develop a “type-lever actuating mechanism for extra-low portable typewriters”.

Borel no doubt saw the possibilities in the Pascher and Julliard designs when he sat down to work on what became the famous Rooy portable.

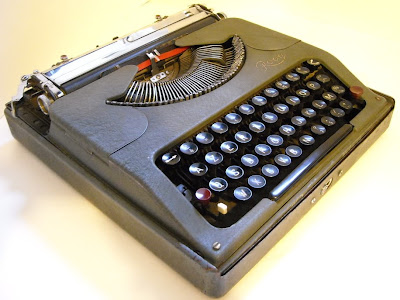

Adwoa's collection.

Unfortunately, Rooy and Royal were to clash in the courts in both Paris and New York when Rooy marketed the Borel portable in the US in the early 1950s.Royal thought not just the name Rooy was too close for comfort, but obviously the logo as well. Royal went first to Paris, where on May 18, 1954, its case was tried by the Tribunal De Premiere Instance De La Seine, Troisieme Chambre, Premier Section.

At this hearing it was found that the word “Rooy” alone (that is, without any other words in the French language) did indeed infringe Royal’s trademark and there was a “likelihood that Rooy may cause some confusion [and deception] as to the source or origin of any typewriter bearing that mark alone”.

Richard Polt Collection

In New York, Royal took legal action against a French citizen, Arnold Alfred Cachelin, who was importing the Rooy into the US under his company trading name Zelandia. Rooys were being advertised by a US department store under the words, “Vive the Rooy! Rooy (pronounced Roy)”.The suit was again decided in Royal’s favour, by Federal Judge William Bondy in the US District Court, Southern Division of New York, on October 4, 1954.

These two legal defeats more of less ended attempts to market Rooys in the US and proved financially damaging decisions for the Rooy company. It went downhill from that point onward, until being declared bankrupt in 1963 (production, in Tours, south of Paris, ended in 1959).

And it is possibly for these reasons that Will Davis was to come to label the Rooy the “Holy Grail” of typewriters. In short, they became an extreme rarity. Apparently, at most, about 76,000 were made.

The court decision came down to the pronunciation of Rooy (“Roy”) and the form and gold colour of the trademarks, on both of which the letter R had a long under curve.

Judge Bondy found that “Accordingly the plaintiff [Royal] is entitled to judgment enjoining the defendant [Cachelin] from using ‘Rooy’ unless the mark used is accompanied by appropriate language indicating that the product is made by the Société Rooy and not by the plaintiff.”

It seems highly likely that the court decisions in Paris and New York led to Rooy adding the letters “MJ” to its branding, as well as to alternate brand names such as Roxy (though still with a defiant curve) and Mascotte.

This stunningly beautiful later model Rooy is from Adwoa's marvellous collection. See more on Adwoa's Rooy on her Retro Tech Geneva blog at

Will Davis in his look at Borel’s Rooy ultra-slim portable says, Borel “clearly [considered] the arrangement of typewriter-in-case previously manufactured was clumsy and cumbersome and thoroughly inconvenient … Borel strove to keep the entire machine and its enclosure as one inseparable entity.”Borel himself wrote, “The box-like cover in which a so-called portable typewriter is enclosed is separate from the same in use, and one can imagine easily how troublesome such an arrangement may be to anyone who has to work in the train or at the hotel or on a desk.”

He also saw the portable as “arranged most easily in a piece of furniture, [such as] in the drawer of a table, and its cover will not constitute a cumbrous object that is of no use during the work or that cannot be located after the machine has been in use for a long time”.

It should be noted that, rather than the sliding action ultimately employed to take the typewriter out of its case, Borel had originally envisaged a design in which the typewriter was lifted on levers and swung around 180 degrees for use:

As for the typewriter itself, Borel wrote, “it must first have the least possible bulk, above all in height, in order to facilitate its handling and carrying.

“A rather great number of so-called portable typewriters have been put on the market which in spite of the substantial difference existing between their height and those of the so-called office typewriters, are nevertheless still much too high and cumbersome to allow their practical carrying by the user”.

Will Davis believes the commercial failure of the Rooy came down to “ideological purity [leading] to manufacturing and design complexity, which naturally led to customer expense in excess of the actual benefit of convenience bestowed by the unusual design”. See Will’s Rooy pages at http://machinesoflovinggrace.com/ptf/Rooy1.html

and http://machinesoflovinggrace.com/ptf/Rooy2.html

Me demonstrating how easy it is to open the Rooy lid, during a presentation in Melbourne in February. This Rooy came to me from Richard Polt, and, having once been owned by such an esteemed typewriter authority, its arrival was one of the high points of my early typewriter collecting. It truly did feel as though I had my hands on the Holy Grail.

Next we look at two typewriter-related patents which were issued on this day in 1889, both from journeymen inventors who, over their many years of inventing, assigned quite a few of their patents to John Alexander Hill.Hill (above, born in Sandgate, Vermont, on February 22, 1858; January 24, 1916) was co-founder of the McGraw-Hill Companies. A railroad engineer, Hill operated machine shops, produced technical and trade publications and in 1896 became president of the American Machinist Press. He served as mechanical engineer for the General Manifold Company, custom-designing machinery.

One of the typewriter inventors who worked closely with Hill was Horace Lucian Arnold. Earlier, in relation to Borel's references for the Rooy, we mentioned Charles Underwood Carpenter, who in 1908 wrote Profit Making in Shop and Factory Management, published by the Engineering Magazine (above).

This was nothing on Arnold, who started out working as a machinist but became a specialist in factory organisation and accounting, writing extensively on manufacturing works management and cost accounting. Arnold published textbooks through the same Engineering Magazine company - and they had such alluring titles as:

Arnold then moved to Ottawa, Illinois, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Middletown, Connecticut, and finally to Brooklyn.

Among his 25 inventions were at least four related to typewriters, including two he assigned to the Union Typewriter Company.

Arnold's inventions from 1858 to 1906 ranged from metal cutters to recorders, book binding, book stitching and book covering machines, mixers, letter locks (see below, with Arnold's name engraved), piston water meters and water motors, knitting machines, “explosive” and internal combustion engines and combustion generators, and clutches.

The typewriter patent he was issued on this day in 1889 was assigned to his own typewriter company. It was for a more durable, four-line typewheel. Arnold wrote that it was designed for a typewriter “in which the type bearer or carrier is adapted to be oscillated to the right or left of the printing point of the machine … and to be arrested and held firmly against movement when the selected character has been brought to the printing-point and the impression is being performed.

“Previous to my invention the type bearers or carriers of such machines have been made in a variety of ways … Type carriers have heretofore been constructed of metal, but were discarded for the reason that when made sufficiently strong to withstand the blow or force at the time of impression, were found to possess so much weight as to make their momentum too great and the touch of the finger-keys too hard and tiresome.”

Arnold wanted a lightweight element but one which would not bend, break, distort. He combined with the element “a rear or internal support or abutment to resist or oppose any force that might break the carrier or destroy the regularity of its shape".

"My invention has for a further object the production of a type-carrier which is adapted to be positively arrested while the printing is being effected; and to this end and object my invention consists, secondly, in a type carrier of cylindrical form, provided on one side with type or printing-characters and on the opposite side with perforations arranged diametrically opposite to said type to receive a locking pin or bolt.”

From one of Arnold's book

On this same day in 1889, William George Spiegel of New York was also issued with a patent for a typewriter, a landmark toy typewriter.Spiegel was born in Wurtemberg, Germany, in September 1858, and arrived in the US in 1880. He worked first as a blacksmith and later as a wheelwright. Like Arnold, many of Spiegel’s 13 patents were assigned to John A. Hill. He invented a marine signal in 1888, a time clock in 1892 and went on to patent a musical instrument using rotating glass tumblers producing notes from friction against rubber, a burglar alarm, aerial signalling, a magic lantern used in advertising and tires and tire moulds – and this automaton:

It looks like something that fellow typewriter inventor, England's John Nevil Maskelyne, might have used in his illusionist's stage show.

Spiegel’s typewriter-related designs included key and actuating mechanisms.But the machine he patented on this day (above) was for one of the very earliest designated toy typewriters. Spiegel said it would be “a very simple and cheap toy type-writer apparatus for the amusement and instruction of children.” It used a strip of paper to type on, which would mean it was very similar to today’s label makers.

Spiegel had a bent toward toy and novelty inventions. His son, also William Spiegel, followed in his father's footsteps in this interest. The younger William Spiegel, however, was to become a star witness in the infamous Alger Hiss case, because he was alleged to have loaned out his apartment to be used to photograph secret State Department documents that Whittaker Chambers said he had received from Hiss in early 1937. Spiegel testified before the grand jury in 1948.

Last but not least, and also, oddly enough, on this day in 1889, George Canfield Blickensderfer was issued with his first typewriter patent. It was not, however, for any typewriter Blickensderfer went on to make. Paul Robert refers to it as the Blickensderfer 0 and says it “probably never came off the drawing board, or Blickensderfer never succeeded in building a fully functioning prototype". It was, says Robert, a “square downstroke typewriter, but the basic concept for rotation of the typewheel was adapted to all later [Blickensderfer] models”.

4 comments:

I just love the Rooy, and thank you for providing further insight. I was not aware of the dust-up with Royal.

The Pascher design may very well be the one that was used the Gromina, the predecessor of the Kolibri, but the Kolibri used a different system, not involving geared typebars such as these.

Thanks very much for your thorough exposé on the Rooy! I am honored to have mine featured and described in such flattering terms :)

I did not know about the legal battles with Royal; that certainly must have been taxing for the company and explains why American Rooys are so rare. In France, I'm afraid I see them up for sale on the local classifieds site fairly often, almost on par with Japy portables! Unfortunately, the azerty keyboard makes those undesirable for most collectors, I would imagine.

I've just bought one of these and there's no ribbon with it. Does anyone know where I can buy a new ribbon complete with spools?

Thanks

Mark

Thank you so much for all this incredible detail! I just picked up a later model similar to Adwoa's (in QWERTY!) and I love everything about it, though it’s missing the handle — would love to get some photos/measurements of a complete handle (perhaps with a ruler alongside) so I can have a new one 3D-printed, if anyone reading this is able to help out…

Post a Comment