- H. Allen Smith (1941)

Writing a story on a typewriter is just putting the

right ends together and then sort of weaving them around the middle.

-

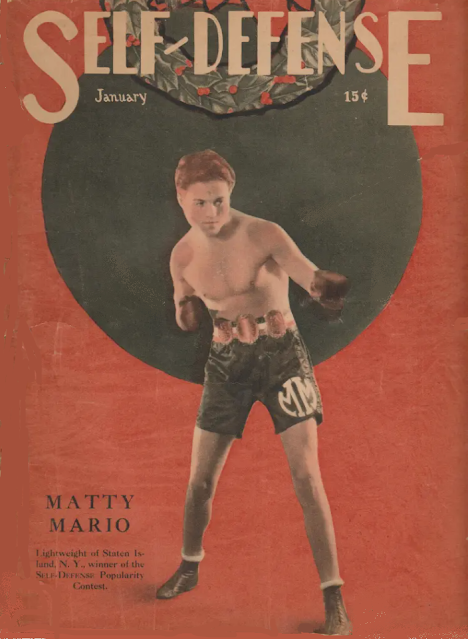

Boxer Matty

Mario (1939)

My wife is a prodigious

reader. Fortunately, we have a vast array of books here, books of much variety

and many vintages, stacked in every room, and sometimes Harriet can dig out and

dust off something she hasn’t already read. One such find was a book given in

1958 to her mother, Pat Horner (author of When Words Fail) by Elizabeth Warburton,

wife of Dunedin-born adult education lecturer Jim Warburton. It’s called The

World, The Flesh and H. Allen Smith, edited by Bergen Evans and published in

London by Arthur Barker in 1954.

Bergen Evans - like H. Allen Smith a proud Midwesterner, unlike Smith a professor of English - selected from the prolific writings of Smith prime pieces to be included in this work. Evans knew good writing when he saw it – indeed he relished it. As Phyllis McGinty wrote in The New Yorker, "I'd take more pleasure in discussions schola'ly / If Bergen Evans wouldn't laugh so jollily." Evans would be in his element today, in this regressive time of pandemic deniers, vaccine sceptics and other Flat Earth believers. He’d have found so much material for his column "The Skeptics Corner", and to follow up The Natural History of Nonsense and The Spoor of Spooks and Other Nonsense.

So, too, would H. Allen

Smith have found today’s world ripe for the picking. As it is, Harriet was delighted

to come across The World, The Flesh and H. Allen

Smith, even though its wonderful array of whimsical yarns about long-gone

characters belongs to another age. On the other hand, Smith could be way ahead

of his time: consider “Naming the Baby”, which predated the mindless monikers

given grievously unfortunate children by present-day celebrity clowns (Reignbeau,

Sage Moonblood, Moxie Crimefighter, Breeze Beretta, Audio Science, Bronx Mowgli,

Moon Unit, Pilot Inspektor). One of the many reasons I love Harriet so much is

that we have the same tastes in humorous writing – we discovered early on in our

relationship that we shared a great passion for the like of S.J. Perelman, Damon

Runyon and Flann O’Brien.

Harry Allen Wolfgang Smith (1907-1976) fits right into that group. He was a journalist and author but most importantly he was a brilliant humorist. Born in Illinois, it was in Huntington, Indiana, that Smith dropped out of high school and, in 1922, found work as a journalist with the Huntington Press. This was the first of a string of newspapers for which he worked. Smith found fame when his book Low Man on a Totem Pole became a bestseller during World War II. This was followed by another bestseller, Life in a Putty Knife Factory, and a third, Lost in the Horse Latitudes. Which enabled Smith to write in 1946 The Truth: How it Feels to Be On the Best Seller Lists For 108 Weeks. His novel, Rhubarb, about a cat that inherits a professional baseball team, led to two sequels and a 1951 film adaptation.

Harriet knew that I would take enormous pleasure in reading many of the articles in The World, The Flesh and H. Allen Smith - and one in particular, titled “The Story of ‘Bad Bad’”. It’s a brilliantly witty piece about a prize fighter called Matty Mario, right, from Dongan Hills, Straten Island, who borrowed a typewriter from a man called Ed Ratigan and on it wrote a book called Bad Boy. All this I can confirm is true – except for Mr Ratigan, of whom I can find no trace. Smith interviewed Matty in 1939, when the boxer was 35. “I typewrite my own stuff,” Matty told Smith. His book, edited by Harry T. McHugh, a teacher at an orphan’s home, was published by Broadway Printers & Publishing Co on February 17 that year. It concerns a boxer called Johnny Conway, fighting under the name Johnny Kid Reed.

Other than what Smith wrote, factually, about Matty, copyright details of Bad Boy and his boxing record, nothing has ever appeared online about Matty – until now. For the first time in Internet history, we can reveal that Matty Mario was Mario Giacomo Ghiselli, who was born to an Italian bartender, Giovanni Ghiselli, and his wife Rosina (Rosie) on MacDougal Street, Manhattan, on October 3, 1904 (Smith said Greenwich Village, which is technically correct). A welterweight boxer, Mario fought 69 times between 1924-44, winning 35 bouts. In the early 1930s he was considered a world title contender.

As Matty told Smith, he had worked on the automobile assembly line at the Ford plant at Edgewater and by the late 30s had become a licensed masseur. During the Second War World he served as what was officially classified a boatswain’s mate class one (BM1) with the US Coast Guard, but unofficially he was a physical fitness and martial arts adviser. This was under a scheme put together by Matty’s friend, the great heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. From June 1942 Dempsey had a commission as a lieutenant and director of physical education for the Coast Guard Reserve at its training station at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. The Dempsey group was released from active duty in September 1945. Unfortunately Matty’s athletic instruction business in Brooklyn had suffered in his absence on war duty and he had to file for bankruptcy at the end of October 1946.

Matty tried selling his movie (Double Cross, In-Law Interference), play (The Unknown Substitute) and TV scripts without a lot of success, but he did find a number of ways to make ends meet. For example, he made trans-Atlantic voyages on the ocean liner the SS America in 1946-54, on the New York-Le Havre-Bremerhaven-Cobh route, working as a passenger’s masseur. While on shore leave, Mario was a pictorial model for fiendish characters in detective magazines, refereeing professional wrestling bouts with comical zeal, and playing villains on television crime shows such as Richard Montgomery Presents. His son, Richard Matthew Ghiselli (1929-1993), was a highly decorated combat veteran from the Korean war. Mario died in New York on August 2, 1977. In some ways - especially in light of his long boxing career - it seems surprising that he outlived H. Allen Smith. But then, Matty may well have been a lot smarter than Smith made him out to be.

1 comment:

Matty Mario is my great grand farther i wanted to see if someone can tell me more about him

Post a Comment