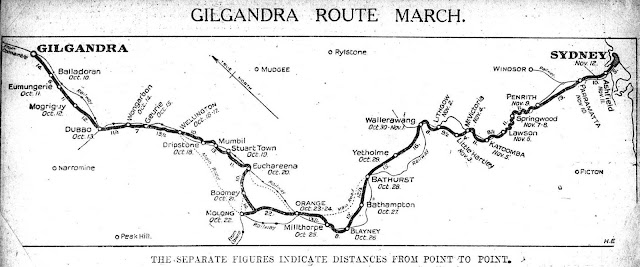

On the weekend of October 2-3, 1915, 43-year-old career public servant Edward Hugh Palmer took his Corona portable typewriter with him on a 546-mile round train journey, northwest of Sydney to the Central West New South Wales town of Gilgandra and back. There was an intense sense of urgency about his mission. Since the beginning of May, five months earlier, casualty lists revealing the slaughter of Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli and on the Western Front had been appearing in Australian newspapers, and the nation was naturally appalled. Many Australians, especially the mothers of enlisted soldiers, quickly formed the opinion that “enough was already enough”. Where once young Australian men had queued up to enlist to fight for the English king and his country, now recruiting had stalled almost to a standstill. Palmer, secretary of the New South Wales State War Council, and a man vitally concerned with recruitment, had on September 1 read news in the Australian Town and Country Journal that a 51-year-old Gilgandra plumber called Bill Hitchen was proposing a “moving army” recruitment march from Gilgandra to Sydney. This was exactly the type of movement Palmer badly needed. Indeed, it was a recruitment officer’s dream come true. As Hitchen and his Gilgandra march organisers cried out for some sort of official endorsement for their plans, Palmer raced to Gilgandra to find out for himself what was happening there. On October 5 he took out his Corona and typed a three-page letter to his superiors in Sydney, strongly advising moral and material support for the Gilgandra marchers.

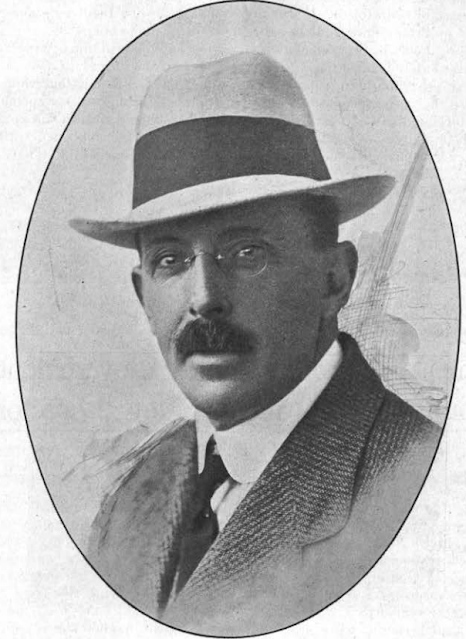

Edward Hugh Palmer

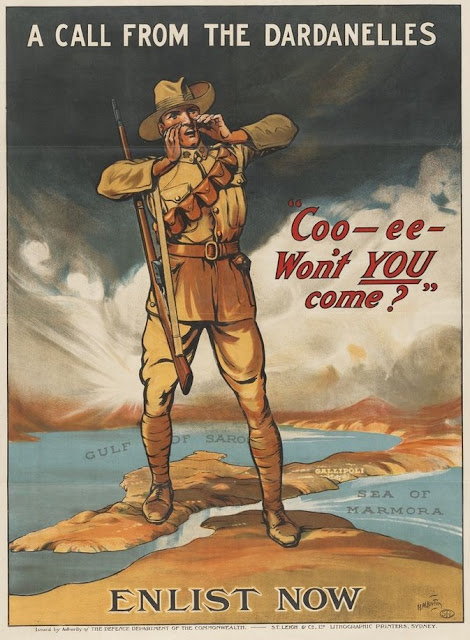

The “snowball march” which set off from Gilgandra on October 10 became known as the “Cooee March”. Twenty-six men started out, led by Hitchen. At each town on the route the marchers shouted "cooee" to attract recruits and held recruitment meetings. By the time they reached Sydney just over a month later, on November 12, the numbers had swelled to 263 recruits. The march had covered 320 miles. Cooee! is a shout originated in Australia to attract attention, find missing people, or indicate one's own location. The word originates from the Dharug language of Aboriginal Australians in the Sydney area. It means “come here” and has now become widely used in Australia as a call over distances.

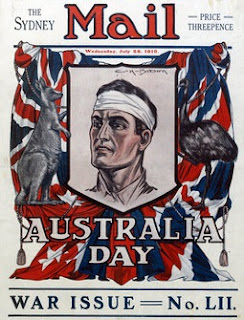

By October 1915 Palmer’s word was near to being gospel in Sydney. He had already organised, with enormous financial success, two appeals, called the Belgian Day Fund and Australia Day Fund. The latter was held on July 30, a date which has no particular relevance in Australian history. Nonetheless, this 1915 event, launched to raise money for the Red Cross to aid wounded soldiers, is considered by some historians to be the first Australia Day.

Medal presented to Mrs Wharfton-Kirke

The idea came from a Mrs Ellen Wharton-Kirke of Manly, Sydney, whose four sons had enlisted and who suggested a fund raising event in this form of Australia Day to NSW State Premier Sir Charles Wade. By August 3, a staggering £739,489 had been raised in NSW, Victoria, South Australia, West Australia, Tasmania and the Northern Territory. That sum surpassed even the massive amount raised in May on behalf of stricken Belgians.

Edward Hugh Palmer, right, born in Sydney in 1872, the son of NSW Civil Service Board secretary Edward Gillett Worcester Palmer (1842-1914), joined the NSW public service himself in 1892. He was moved from treasury to become one of the first officials appointed to the NSW Premier’s Office when it was established in 1907. In 1912-13 he was sent to London on special duties, working for the NSW Agent-General Sir Timothy Coghlan. Back in Sydney, Palmer, as well as being the driving force behind the two fund raising events, was deeply involved in pushing for the creation of Anzac Day, first celebrated in 1916, as well as with repatriation for soldiers. He later became superintendent of the NSW Immigration and Tourist Bureau and resident controller of the Jenolan Caves, limestone caves in the Central Tablelands region, west of the Blue Mountains, 109 miles west of Sydney. The caves are the most ancient discovered open caves in the world and include Silurian marine fossils.

New South Wales was hit by the “Spanish flu” pandemic on January 27, 1919, and a month later it reached Jenolan. Palmer coordinated the response and converted his bungalow residence to a hospital. He organised for doctors to tend to the sick and installed an inhaling chamber. The NSW Government approved of Palmer’s suggestion to use Caves House for 40 convalescent nurses. Palmer retired at the end of 1921 because of ill-health and died at Bulli on February 26, 1922, leaving a widow and three children.

*Today, January 26, is

Australia Day, as it has been nationally since 1935. It marks the anniversary

of the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and the raising of the

Union Flag by Arthur Phillip.

1 comment:

What a great article! I work at Jenolan Caves, and today I was doing my daily online search for news about Jenolan and found your article. I am fascinated by history of Jenolan, but I've never seen much info about Edward Palmer, although I did know about his work at Jenolan during the Spanish Flu pandemic.

Post a Comment