After being successfully revived in a nine-day festival in Athens in

1896, the Olympic Games became a rambling shambles in Paris in 1900 and St

Louis in 1904, when the Games were at best a sideshow to World’s Fairs. The

focus was back on sport when London stepped in for Rome in 1908, but as

with Paris (21 weeks) and St Louis (19 weeks), the London Games meandered on

for a ridiculous 24 weeks. Stockholm in 1912 cut that down to 10 weeks, and staged

well-organised Games which steered the Olympic Movement back to its original

concept.

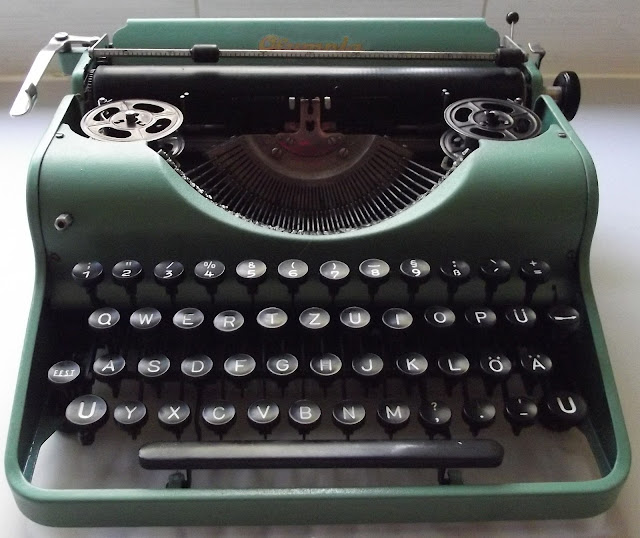

The 1912 Olympics were also the

first to take into planning consideration the needs of the Press. Designated Press stands and other facilities were provided at the main venues. With the

Games being more concentrated, it became more feasible for overseas newspapers

and Press groups to justify sending typewriter-wielding reporters to cover the

events. Coincidentally, it was also possible for the journalists to take with

them lightweight, compact portable typewriters, such as the Corona 3, which had

come on to the market that same year.

Still, it is interesting

that as many as 257 foreign journalists were accredited to cover the Stockholm

Games.

Members of the Press watch the 1912 Opening Ceremony

The United States, for example,

sent 28. Among them, and highly appreciative of the arrangements, were Robert M.

Collins of the Associated Press of America, William Orton Tewson of The New

York Times, Charles Wilbur Williams of The New York American, William G.

Shepherd of the United Press Association, Paul M. Whelan of the New York Sun

and James S. Mitchell of the New York Herald. Two also travelled from

Australia, James Hill of The Sydney

Morning Herald and C.S.Cunningham of the Melbourne Argus.

The Stockholm Organising Committee also used “a dozen

clever lady-typewriters” to mass produce results and schedules for the Press

representatives. Under Press Commissioner Dr David Wahlberg, Stockholm had

the first dedicated Olympic Games Press Office. Wahlberg “hired half a dozen

type-writing machines which were placed on the tables …”

Sadly, the 1920 Antwerp Olympic

Organising Committee went bankrupt and as a result no official report of the

overlong (19 weeks) Games was produced.

However, in 1957 the Belgium Olympic

Committee was able to bring out a typewritten report based on what records had

been kept in the intervening 37 years in its archives in Brussels.

The 1924 Paris Olympics took up where Stockholm had

left off in terms of facilities for the Press. Paris organisers provided a

Press Centre at the main stadium at Colombes which included many “type-writing

machines”. The centre had an adjacent telegraph-office. The Games, however,

dragged on for 11 weeks.

Even greater progress was made before the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics.

In the lead-up, a number of rooms at the organising committee’s apartments at

the Heerengracht were fitted out as a Press Bureau.

“At the De Groote Club

‘Doctrina et Amicitia’ in the Kalverstraat, the whole of the lower floor was

placed at the disposal of the Press … The Press Stand in the Stadium was made

to seat about 600 persons. In front of many of the seats there were small

folding tables on which a typewriter could be placed or notes made.”

Amsterdam organisers, however, took care to have

“waiting-rooms for the members of the Royal Family and the members of the

International Olympic Committee … Another entrance was planned for the Press,

and by this means it was possible to house the Press in separate quarters of

their own, and to prevent undesirable contact between journalists, contestants

and officials.”

The 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games,

which opened 80 years ago yesterday, might have been held at the height of the

Depression and in a geographically isolated part of the world, yet they broke all

records by accrediting a staggering 809 Press representatives.

Central Press Stand, LA Memorial Coliseum:

Note the rolls of paper underneath the boxes containing the typewriters

Damon Runyon

These included such famous American writers, sports

writers and sports figures as Ty Cobb, Damon Runyon, Grantland Rice, Paul

Gallico, Westbrook Pegler and Irving Wallace. Wallace’s son, David

Wallechinsky, would many years later produce the brilliant series of doorstopper books under the title The

Complete Book of the Olympics.

Grantland Rice

The Los Angeles Olympics were also the first to

provide typewriters in bulk to visiting journalists, including 190 portables, 19

standard-size machines and 10 electric typewriters.

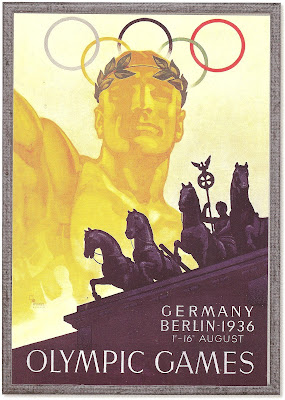

For the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, organisers allowed

for 1000 Press representatives in its main stadium.

An American reporter, cigarette dangling from his mouth, taps away

on a Remington portable in Berlin

“The seats in the Press box

were provided with writing desks so that the reporters could make written or

typewritten notes during the course of the competitions. An office equipment

firm delivered typewriters with the different keyboards for use in the very

popular writing room.

"Six typewriters, including two electric ones, were

provided for the main office, and these were constantly in operation.

"The Press

post office was situated immediately under the Press box, and with its 50

telephone booths, numerous counters for telegrams and mail as well as 80

writing booths and 63 typewriters supplied by the Organising Committee, it was

adequate for meeting every demand.”

The “Press quotas” included 593 foreign journalists,

46 of them from the United States and another 39 from Great Britain. In all,

the Berlin organisers estimated at least 2800 journalists were involved in covering

the 1936 Games.

Organisers of the 1948 London Olympic Games had all

sorts of immediate post-war problems to overcome, including supplying

typewriters. “Typewriters were hired and in some cases purchased, but these

found a ready market after the Games and were therefore not a liability.”

Eighty typewriters were supplied for staff and Chefs de Mission “at a nominal

fee”. The Press, however, had to fend for themselves, in a period when major

typewriter manufacturers were just converting back to production after the six-year war period, during which very few new typewriters had been made in the US, Germany

or Britain.

It was a different story at the 1952 Helsinki Olympic

Games.

Not alone was the Press provided with 206 typewriters, but the

scoreboard at the main stadium was operated by “an ordinary typewriter”.

Helsinki also issued a record 1848 Press passes, 86 of them to Americans and 81

to German reporters.

The Olympic Games came Down Under the first time in

1956, when Melbourne withstood pressure from the International Olympic

Committee president Avery Brundage to make a late switch to Philadelphia. The

out-of-season Games finished up being well-organised, ready on time, and a

success. However, the apparent tardiness in earlier planning, to which Brundage had

objected, meant there were insufficient volunteers to cover such tasks as

handwriting participation certificates.

The Olivetti Typewriter Company, which had been

trying to get a toehold in the Australian market, stepped in and “produced a

machine with specially large type (3/16 of an inch) which was found to be

satisfactory and had the advantage of speed and economy.”

The gains in the promotion of Olivetti typewriters are obvious from the images below. Olivettis are everywhere the eye can see:

Avery Brundage visits the Main Press Centre

The arrangement led,

for the first time, to a typewriter company becoming an official Olympic Games

supplier, and in exchange Olivetti was given the rights to supply Studio 44

typewriters to all Press centres and Press boxes, as well as Lettera 22 portables “on

loan” to visiting journalists.

There were 800 accredited journalists, of whom 511

had desks for telephones and typewriters. Typewriters were available on working

desks with keyboards in English, French, German, Italian and Russian.

“Typewriters were available at other competition venues and portable

typewriters were lent to journalists at their hotels.” Most were never returned, but instead went on to newspaper offices around the world.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)