How the Benedict Family

Battled for Henry’s $50 Million

Gamble “Gambi” Benedict

Poor Little Rich Girl

Trapped in Manhattan Gilded Cage

by Ogre

Grandmother

When typewriter heiress Gambi Benedict broke the law and eloped

with a still wedded Romanian chauffeur in early 1960, she drew the focus of the

world’s Press on her family’s vicious squabbling over the inheritance of

Remington typewriter pioneer Henry Harper Benedict. What was dubbed the “Remington

typewriter fortune” was variously estimated at being worth between $50 million

and $90 million.

Gambi and Andrei look as though they prefer

something else to a Remington

Nineteen-year-old pampered Manhattan princess Gamble “Gambi”

Benedict declared it wouldn’t matter if she munificently threw away her vast

share of this fortune (a cool $20 million) to marry her money-grabbing Lothario.

She would instead “pound a typewriter to pay the rent”. “I’d rather be a

typist,” she said, than a “poor little rich girl trapped in a gilded cage”. “I’ve

done nothing to deserve this money, nothing to earn it. If Grammie won’t accept him,

I’d rather take a job and hammer away at one of her typewriters from 9 to 5.”

As reporters and photographers clambered outside the Benedict town

house at No 5, East 75th Street, Manhattan (“the size of a small Swiss hotel”) waiting

for a glimpse of Gambi and her grandmother – Henry Benedict’s widow - members

of the Benedict family and other bit players in this long-running real-life

soap opera queued outside New York’s courts waiting for their turn to throw vitriolic accusations at one another. It was on for the very young and the very old, all in

no uncertain fashion.

Police escort Gambi, right, and her "Grammie" from the

New York Girls' Term Court in January 1960

The legal combat took a deadly toll, with Henry’s widow and one

of his daughters dying from the stress of it all at the height of this drawn-out

imbroglio.

Katharine Geddes Benedict keeps up a brave face

Both Gambi and Henry’s daughter by his first marriage, Helen Elizabeth

Benedict Forrest, took the stand to accuse Gambi’s grandmother, Katharine

Geddes Benedict, of concealing their share of the Benedict millions. Katharine,

as it turned out, had squirrelled the mullah away all right – in toilet cisterns

and kitchen drains, among other unsavoury places. Gambi also charged her

“Grammie” with illegal confinement, while “Grammie” was sued by the Romanian

chauffeur and his legal wife for much the same thing. The bottom line for many

of these court actions seemed consistently to be: hand over $1 million, thanks

Gram, and be quick about it.

The Gambi Benedict affair was the stuff of dreams for newspaper

and magazine editors and television producers, right across the globe. These

seemingly endless, increasingly lurid stories, about a lovestruck, naïve girl

called Gamble, were a sure bet to make page one anywhere on earth. They were,

after all, based squarely on the wages of the cardinal sins: avarice, lust,

envy, wrath and vainglory. They were about wagers against disinheritance, risks

of being caught gambolling about in an illicit affair with an older married man,

or hiding away millions in inheritance money that rightfully belonged to

others. Readers and viewers loved it, and lapped up every syllable.

Gambi and Andrei on their honeymoon in New Orleans

Here was the archetypal “poor little rich girl”, trapped in a

“gilded cage” in Manhattan by an ogre of a grandmother and made a ward of the

court to stop her seeing her chauffeur in a shiny refugee’s suit. Fairytales are

made of lesser raw material.

The story had all the trappings of a major, memorable melodrama.

When Henry’s second wife, the evil “Grammie”, otherwise known as Katharine

Geddes Benedict, suddenly dropped dead at the peak of the scandal, US Tax

investigators found millions in cash and jewels stashed away under her bed

mattress, in her kitchen drains, her toilet cistern and in bedroom closets.

Those awful, wayward kids weren’t going to get their greedy hands of

“Grammie’s” money, no way!

LIFE magazine went hot

and heavy on the Gambi story, running her on its front cover in full colour and

devoting many pages to three seriously slanted major features on her antics.

One disgruntled female reader wrote, “Can it be that all the world's problems

are solved at last? LIFE must think

so if the most prominent news story it can find is the Gamble Benedict

frivolity.” Ouch!

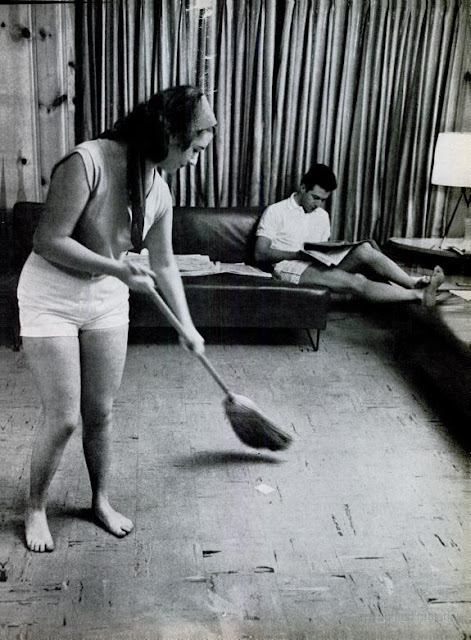

While Andrei puts his feet up, Gambi does some housework.

Apparently she also had to mend and iron her own clothes.

Some American columnists tried to sound sympathetic towards Gambi. After all, they wrote, being filthy rich and having servants wait hand

on foot on you isn’t all fun and skittles. There are responsibilities attached

to having this sort of dough. What’s more, Gambi had just turned five by a

month when her mother, Josephine Catharine Benedict Sharpe, Henry’s daughter by

Katharine Geddes Benedict and the wife of a Vermont psychiatrist, swallowed 50

sleeping pills in her New York apartment one night in February 1946 and died.

No wonder Gambi was a somewhat troubled little lass.

Gambi and older brother Doug in 1947, the year after their mother suicided

Did I say this would make movie material? And there’s even a

sweet, innocent young orphaned Gambi in it!

Where did Gamble get her unusual (at least for a girl) name? Her grandmother, Katharine Geddes Benedict, was the grand-daughter of the Very Reverend Dean John Gamble Geddes, of Hamilton, Ontario, who was the son of Sarah Hannah Boies Gamble, the daughter of John Gamble. John Gamble was born in Enniskillen, Ireland, in 1755, the eldest son of William Gamble of Duross. John was a surgeon in the Queens Rangers who arrived in New Brunswick in 1783 and settled in St John and Maugerville, Sunbury. He moved to Ontario in 1798. Sarah Hannah Boies Gamble was born in Maugerville on April 6, 1788.

Gamble's great-great-greatfather, the Very Reverend Dean

John Gamble Geddes, of Hamilton, Ontario

For typewriter historians, the really interesting aspect of this

saga is that it occurred at the very time when Remington, by then part of the

Sperry Rand Corporation and about to move production from Glasgow to Holland to

avoid labour troubles and mounting costs, was struggling to keep its head above

water. And here were the Benedicts at one another’s throats over $50

million! Where was the justice?

Sitting pretty: Remington wasn't at this time

In all fairness, it would seem Henry H. Benedict’s massive

fortune was accumulated not so much through his Remington typewriter

manufacturing and sales ventures as from his astute investments in art: in the

works of James McNeill Whistler in particular.

Thomas Gallagher

Ironically, when all the dust had just about settled on the

Gambi Benedict affair, Gambi married and settled down with a square-jawed New York cop,

Thomas F.Gallagher. Ironic, because Gallagher in the 1970s posed in a sting

operation as bent cop “Tom Gordon” and proceeded

to recover from crooked art dealers $2.5 million worth of art works, including

a Rembrandt, which had been stolen from the Eastman Collection in Rochester and

had found its way to Montreal.

But I digress …

The Fortune Maker: Henry Harper Benedict

Let’s start at the beginning, with Henry Harper Benedict. After

all, the Remington typewriter (as opposed to the typewriter) story starts with Henry H. It was Henry who in

February 1873 gave the word which convinced Philo Remington to commit

E.Remington & Sons of Ilion, New York, to make the Sholes &

Glidden.

A slightly younger Henry

Henry Harper Benedict was born at German Flats, Herkimer County,

New York, on October 9, 1844, and educated at local public schools, the Little

Falls Academy, Fairfield Seminary, Marshall Institute at Easton, and finally Hamilton College, Clinton. He entered

Hamilton in 1865 and graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in 1869. In 1923

he was also made a master of arts and a doctor of law. Apart being the master

of picking winners in typewriters, he was also a master of the art of investing his Remington earnings. In later life, he was described as a banker.

Benedict first married Maria Nellis (born Freys Bush, New York,

March 7, 1840), the granddaughter of General George H. Nellis, on October 10,

1867. She was 27, he was 23 and a day.

On October 11, 1879, a day after their 12th wedding anniversary,

Henry and Maria had a daughter, Helen Elizabeth Benedict. Exactly 81½ years later, this same daughter, as Helen Benedict

Forrest, would add considerably to Katharine Geddes Benedict’s woes, by

emerging from obscurity to sue for her share of her late father’s millions.

Helen was “spurred” to do so, she said, by the publicity surrounding Gambi’s

shenanigans. Helen declared herself a step-aunt of Gambi, and said Katharine,

though four years her junior, was her stepmother. Helen had married Archibald Alexander

Forrest, a real estate agent for whom a generous father-in-law had nepotistically

found positions in the Union and Remington typewriter companies, as a director

and vice-president of both, no less.

"The Crumbs of the Rich"

Immediately after graduating from Hamilton College, in 1869

Henry Benedict joined E. Remington & Sons as a bookkeeper and rose through

the ranks to become Philo Remington’s private secretary and treasurer of the

Remington company’s sewing machine division.

Clarence Walker Seamans

William Ozum Wyckoff

In 1882 he joined Clarence Walker

Seamans and William Ozum Wyckoff to form Wyckoff, Seamans & Benedict to

make and market Remington typewriters. Benedict became president of Wyckoff, Seamans & Benedict from 1895 and was also president of the Remington Typewriter Company from 1902

until retiring a wealthy 68-year-old in 1913. He was a trustee of Hamilton College,

the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the American Scenic and Historic

Preservation Society and the National Institute of Social Sciences.

The former Nurse Geddes

Maria Nellis Benedict died on August 25, 1915, aged 75, leaving

Henry a 70-year-old widower. At that time, Canadian-born Josephine Katharine

Magill Geddes (born Hamilton, Ontario, 1885), who had arrived in the US in

1905, had been listed as a servant in the Benedict household for at least five

years. In 1961 it was claimed Geddes was a nurse who had “attended” to Henry H.

Benedict through an illness in 1917. Within 10 years, Mrs Geddes Benedict was in

control of Henry’s finances, taking action against Goodyear as a major

stockholder.

Henry Harper Benedict died, aged 90, on June 12, 1935, leaving

his widow Katharine – and presumably his daughters Helen and Josephine, too –

exceedingly wealthy woman, no more so than, if not exclusively, through Henry's

massive art collection.

Henry started building the collection while travelling overseas

as the head of Remington’s international operations. In 1901 he acquired the only

known work to have been sold in Whistler’s lifetime (two years before Whistler died), the watercolour Off the Brittany Coast.

.jpg)

In quick time

Henry amassed a distinctive collection of Whistler etchings and small works

(drawings, pastels and watercolours). He was generous on lending them to, for

instance, the Whistler Memorial Exhibition in Boston in 1904. Henry’s

collection of engravings and etchings by the great masters grew into one of the

world’s largest and most impressive, and he added to it oil paintings by contemporary

American artists. A Turner impression finished up in the Tate. He owned etchings

by Alphonse Legros. He had a particular interest in sketches and working

drawings, and probably bought them cheaply. A

Portrait Study of a Lady sold at Christie's on December 13, 1910, for £4.

Some came from the collections of T.R. Way and H.S. Theobald in London. Henry Benedict

had several fine Venetian pastels, including Whistler’s Calle San Trovaso. In 1920 loans from Benedict’s print collection

were made to an exhibition celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York.

.jpg)

All this was left to Katharine and Helen to fight over. There

had been a major falling out between Helen and her father over Katharine, whom

Helen disliked and mistrusted intensely.

Helen, described by Henry as “hysterical” over the matter, had demanded

Henry sign-over a $500,000 trust fund from her inheritance, to “keep her

quiet”, before he died. As things

transpired, she had very good cause to take such precautions.

No mention here of an extremely valuable art collection

Eighteen months after Marie’s death, on March 5, 1917, Henry and

Katharine (also known as Katherine and Kathleen) married.

They had the one

child, Josephine Catharine Benedict, who was born in Manhattan in June 1918. In

January 1938 Josephine married Brattleboro, Vermont, psychiatrist James Douglass

Sharpe and had two children, daughter Gamble Benedict Sharpe and son Douglass Geddes Sharpe

(born 1939). After Josephine’s suicide, on February 9, 1946, Katharine Geddes

Benedict fought a long, bitter and controversial court battle against Dr Sharpe

to win custody of her two grandchildren. Sharpe would also have no control of

their inheritance. In the hearing, Geddes Benedict had accused Sharpe of

“killing” her daughter after a quarrel. The two Sharpe youngsters, wards of

Geddes Benedict and no doubt growing up to be told this was true, were to adopt

the Benedict surname.

Dr Sharpe and his new wife are stopped from seeing Gambi in 1960

Gamble Benedict Sharpe Gallagher was born in New York on January 15, 1941,

and graduated from Chapin School in 1959. Her school yearbook mentioned an

interest in art and alluded to “suppressed desires” – if only her school

friends knew!

At 18, she was a darling of the Southampton summer smart social set,

the “junior jet set” as they were called. Gambi was the pampered, protected

princess at parties at the Meadow Club, where the Benedicts spent much of their

summers.

Like Katharine Geddes Benedict, other women who had married into

considerable wealth summered in Southampton. One notable, rather notorious,

example was Ileana Maria Pociovalisteanu Kerciu Bulova (later Mrs Auguste Lindt).

Ileana Bulova

Ileana, born in Târgu Jiu, Romania, on September 29, 1919, was the merry “widow” of watch king Arde Bulova. I put

widow in inverted commas because Ileana’s marriage to Bulova was in tatters

long before he died of cancer, on March 18, 1958, aged 68. In 1953, US

authorities had investigated Bulova’s dealings with a Swiss cartel, and it

emerged he (and his wife) had very close connections with high-powered people

in Zurich, and with Swiss diplomats in Washington and the US consul in Zurich. Bulova

also had “substantial” assets in Switzerland and had bought his wife a $400,000

home in France. They had met in Switzerland, where Ileana worked as a maid in

Bulova’s house, in 1952, when Bulova was 65 and Ileana 32, and they were married

in New Jersey later that year. The couple “sojourned in Switzerland for

extended periods”. (Note: Bulova was involved in another “curse story” – see here.)

Ileana Bulova

I mention all this because Ileana Bulova, with a summer home in

Southampton, close to the Meadow Club, a live-in Romanian chauffeur, an

apartment in Paris and a 20-room chalet in Zurich in which Gambi later stayed,

was to play a hitherto unexposed but pivotal role in the Remington typewriter

fortune events which were about the unfold in the winter of 1959-60. Ileana not

just encouraged but aided and abetted Gamble Benedict all along the way.

Gambi had been pursued by eligible young bachelors of her own age

group, but she yearned to be rescued from the constraints placed upon her by

her “Grammie” in the stuffy family home in Manhattan. She had idealistic

visions of her prince charming whisking her away from all this, taking her to a

rose-covered cottage far away.

Andrei with real wife, Helma, and daughter Georgette

Andrei Porumbeanu (born January 27, 1925) was charming, and came from far away, but he was

no prince. Indeed, he was a genuine pauper. When US newspapers called him Gambi’s

“swain”, some felt they’d put an “a” in the middle instead of an “e” at the

end. One reporter wrote, “Since nobody can pronounce his name, we call him ‘Poor-No-More’.” Gambi’s brother Doug called him a “miserable

cad”, others found “rogue” sufficient.

‘Poor-No-More’ Porumbeanu was Ileana Bulova’s chauffeur, a man

of 34 with an Austrian wife, Helma, and a small daughter, Georgette. In the

early summer of 1959, while Ileana Bulova was overseas, she lent Porumbeanu the

keys to her Southampton home. Porumbeanu saw the chance for some respite from

his humdrum, threadbare existence, to experience, albeit briefly, the high life, to throw

his own raging parties and rack up the costs on Ileana Bulova’s tab. He would live a big,

expensive lie, just for a little while … no real harm would come of it.

But then in May 1959, at a party given by real estate agent

Russell Burke, Porumbeanu met a charming young lady of almost half his age. Not alone was Gambi Benedict 18 and

attractive, but she was worth many, many millions, she was the typewriter

heiress. Porumbeanu reasoned that if he played his cards right, he would be

able to live this high life on a more permanent basis.

Gambi and Porumbeanu began an affair – Gambi doubtlessly not

knowing the truth about her first lover, but being taken in by his lies. Over

the next seven months the pair plotted Gambi’s escape from her gilded cage in

Manhattan, from her Grammie, so she could live and study in Europe and marry her

prince charming.

Gambi cleverly ensured she maintained the pretence of living the

life of an 18-year-old heiress. On December 23, 1959, looking radiant, Gambi

made her debut at the grandiose Debutante Cotillion and Christmas Ball in the

Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria. Three days later, she attended a “coming

out” tea dance given by Katharine Geddes Benedict at the swish and exclusive

Colony Club in Southampton. Through all this, Gambi showed no sign that anything was afoot. As far as the Benedicts could tell, all was well, all was

going to plan in Gambi’s life.

At four o’clock on the morning of December 27, Gambi woke up,

dressed, packed and let herself out of the Manhattan home. She made her way to

Pennsylvania Station, where she met Porumbeanu. For four days the pair hid with

Porumbeanu’s friends in New York City. On New Year’s Eve, they boarded the

Norwegian freighter Edga.

On the

passenger list, Porumbeanu wishfully described himself as an “economist”. How very drool! After

an eight-day crossing, the couple reached Antwerp. They spent an extra night

on board, as the freighter was late and that night’s connecting train for Paris

had already gone. They told crew they were to get married in Paris and then

carry on to Italy.

In Paris they decided against staying with Ileana Bulova – that

would have been too obvious – but instead moved in with a friend of Porumbeanu,

Jean Cosacesco, a Romanian-born lawyer.

Back in New York, alarm bells were ringing. Geddes Benedict had

been temporary thrown off guard by a red herring, a false telegram from Mexico. Gambi’s

friends were interrogated. There was talk of a “German” companion. Eventually the

clues were pieced together, and the trail was uncovered. Katharine Geddes

Benedict contacted police on January 3, but fearing a scandal, insisted Gambi

not be reported as a missing person. Money had other ways of working these

things out. Instead, Grammie put attorney Robert Hoffman on to the case.

Gambi, meanwhile, feeling for the first time all the joys of her new-found freedom, was only too willing to talk to the Press. No hiding her

light under a bushel, or anywhere else for that matter, for her. She openly

talked of studying at the Sorbonne and of using her riches to help "struggling

refugees, intellectuals and artists”. Hoffman flew to Paris and began to follow

the lovers. Meanwhile, he made contact with French police and court officials.

When he was good and ready, he summonsed Gambi’s brother Doug, then a young

private in the US Army, to join him in Paris, and they pounced.

Big brother Doug brings Gambi back to the US

On the night of January 22, 1960, Doug contacted Gambi and arranged a meeting. Gambi and Porumbeanu grabbed a cab outside a

nightclub and set off, only to be ambushed by French police. It was a set-up.

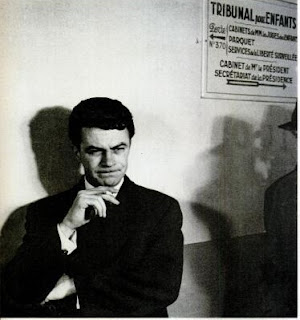

A disconsolate Andrei sees his fortune slipping away outside a Paris court

The next morning Gambi was dragged before Judge Pierre Roland-Levy

in the Tribunal pour Infants, the juvenile court of the Tribunal de Police de Paris. She was placed into

the custody of Doug, to immediately be taken to Orly Airport and flown

home with Doug and Hoffman to the US. Porumbeanu

wasn’t let near her before she left.

Gambi and Doug leave the plane in New York

That night Gambi, Doug and Hoffman arrived at Idlewild Airport

in Queens on a Pan-Am airliner. Someone had tipped off the Press. Gambi was

calm when she landed and went through immigration. But she soon flew into a

panic. She screamed to Doug to get her away from the jabbering, bulb-flashing

mob.

Gambi was rushed out of the airport under police guard and taken

back to the Benedicts’ Manhattan home. No one was allowed to see her. Even her

own father, and his new, pregnant wife Marylyn, were turned away from the Benedicts’

front door. Someone was unkind enough to scrawl “Heil, Granny” on the front

doorstep.

Mrs Geddes Benedict arrives at court. Gambi is behind her

In Gambi’s absence, Katharine Geddes Benedict had found out all

she could about Porumbeanu – that he was married, but that he had promised

Gambi he would get a divorce and marry her. Grammie acted swiftly. She tracked

down Porumbeanu’s wife, Helma (aka “Madi”)

and had her and her daughter Georgette (“Gigi”) just “disappear” for a while.

Without Helma, Porumbeanu couldn’t get a divorce, even a “quickie” in Mexico,

and a heavy spoke would be put in his wheels.

But Porumbeanu had managed to follow Gambi back to the US. He

soon found his wife and daughter were “missing”. Sensing his chance of a

millionaire’s lifestyle was rapidly drifting away, Porumbeanu hired a lawyer and

had law clerk Jack Ginsberg try to serve a writ on Katharine Geddes Benedict to

“hand over” his wife. Ginsberg, turned away by a maid, attached the writ to the

Benedicts’ front door. On February 2, Porumbeanu told a court Geddes Benedict

had “hidden his wife” so she could not consent to a divorce.

On January 27, Porumbeanu's 35th birthday, Geddes Benedict petitioned the New York Girls'

Term Court, alleging that Gamble’s “conduct has been such as to injure her

health, morals and welfare by reason of the fact that she has left the country,

has been associating with a married man, father of one child, one Andre

Porumbeanu, and has been getting beyond control of the petitioner”.

Porumbeanu was there the next day when Gambi was brought before

the court, in the New York State Supreme Court building in Manhattan. He no

doubt winced when Grammie pronounced him a “penniless refugee” and a

“fortune-hunter” (both claims true, as subsequent events would establish). “Gamble

doesn’t know what she’s let herself in for,” warned Geddes Benedict. How right

she was, on all counts.

Gambi was made a ward of the court and placed back in the care

of Grammie, while the judge weighed up “the moral, social and legal implications”

and whether to decree her a wayward minor. She was also ordered not to see

Porumbeanu, who, more significantly was ordered to attempt no contact with Gambi.

As part of her parole, Gambi was to have mental and physical

examinations. The Benedicts took precautions: they moved Gambi into another

Benedict house on East No 75th Street, at No 42, where she was watched over by

brother Doug.

Gambi and Porumbeanu, however, somehow managed to resume their plotting.

Gambi had a note smuggled out, scrawled on toilet paper, declaring her

ongoing love for Porumbeanu and saying she was being held captive by Doug.

Gambi did get out of this second Manhattan gilded cage. On April

5, a New York court magistrate issued a warrant for her arrest for “absconding

from home” and violating court orders. The next day, the same magistrate issued

a warrant for Porumbeanu's arrest “because [Gambi] was in his custody and

control.”

Porumbeanu had acted quickly. Though down to his last $10, he

had borrowed money from a Romanian political scientist, Cornel Pope. Porumbeanu

and Gambi took a train to Wilmington, Delaware, then a plane to Raleigh, North

Carolina, hoping to throw Katharine Geddes Benedict and Robert Hoffman off their trail. In Raleigh, the

pair find the Press are already on to them and, told to wait a day for a marriage licence, decide to move on. They rented a car and headed to

Hendersonville, North Carolina. There they had blood tests hurriedly done and

got a marriage licence from county register of deeds Marshall Watterson.

That night of April 6, in a single-ring 10-minute ceremony on

the lawn outside a mountain hunting lodge eight miles from town, owned by

county attorney Arthur J.Redden, Redden “gave the bride away” and Justice of

the Peace Fletcher Roberts declared the two legally “man and wife”. It was a

simple, straightforward service, but it wasn’t legal at all.

Porumbeanu had convinced Redden, Watterson, Roberts, Gambi and

others that just six days earlier he had been granted a divorce from Helma in

Mexico. Much later, after the rose tinting had fallen from Gambi’s glasses, she

learned that he was not legally divorced. Helma had not resided in Mexico and

had not consented to the divorce. Porumbeanu, overcome by his greed, had

allowed himself to become a bigamist.

Gambi and Porumbeanu honeymooned in New Orleans, with Porumbeanu

telling all that he had lined up an assistant manager’s job in a plush hotel in

Miami. Gambi and Porumbeanu, however, had broken the law, they were both held

to be in contempt of the New York courts. More trouble lay ahead. And there was

much trouble coming for Grammie too:

June 30, 1960: Gambi and Porumbeanu seek to “vacate the warrants of arrest” against them “on the grounds that they had been married …that she is now emancipated; and that they are both happily married and reside in Montclair, New Jersey”. In July their application is rejected and the arrest warrants stay in place.

February 24, 1961: Helen Benedict Forrest sues Katharine Geddes Benedict

for fraud, claiming Geddes Benedict had concealed Henry H.Benedict’s will when

he died in 1935. Forrest also claimed Geddes Benedict had “estranged” Henry

from his family and friends. “It was inconceivable he would not have left a

will providing for his family, inconceivable that he would have bestowed his

entire fortune on his second wife,” Forrest said. Forrest said she had been

lulled by Geddes Benedict into believing Henry had died leaving no assets, but

had discovered otherwise during the Gambi business.

April 2, 1961: Gambi gives birth to her first son, Gheorghe

Mihail, in a community hospital in Montclair, New Jersey. The couple cannot

return to New York while contempt of court charges are proceeding.

April 20, 1961: Two months after opening fraud proceedings

against Katharine Geddes Benedict, Henry Benedict’s eldest daughter, Helen Elizabeth

Benedict Forrest dies, aged 81.

August 29, 1961: Gambi begins legal action to remove Katharine Geddes

Benedict as her legal guardian.

September 1961: Helma Porumbeanu sues Katharine Geddes Benedict for $1

million for attempted bribery and being “used as a pawn to prevent” her

husband’s divorce from her. Everyone wanted a grab of Grammie’s millions. It was all too much for Gram ...

October 29, 1961: Katharine Geddes Benedict dies, aged 76, at

her home “of natural causes”. Gambi and her brother Doug will eventually each

be bequeathed $20 million. That equated to two-fifths of the estate each. US Tax

investigators find almost $2 million in cash and jewelry stashed in Geddes

Benedict’s home.

November 17, 1961: Porumbeanu is found to be in criminal

contempt of court for violating court orders not to associate with Gambi.

January 5, 1962: Gambi and her brother Doug seek to be allowed

to receive a share of the accrued income from the Remington typewriter fortune.

January 1963: Gambi’s second son, Grigoreo (Gregoire), is born.

September 18, 1963: Gambi announces she is ending her “marriage”

to Porumbeanu.

September 18, 1963: Gambi and her two sons leave Rome and go into

hiding in Zurich to avoid Porumbeanu, who she is suing for “misconduct”.

Gambi "in hiding" in Zurich

Gambi

had also cancelled Porumbeanu’s power of attorney over her income from her $20

million inheritance trust fund. She labelled Porumbeanu a “fortune hunter” and

claimed he had already squandered $500,000 of the Remington typewriter inheritance.

Gambi with Georgette and Helma Porumbeanu at the annulment hearing

October 7, 1964: Gambi is granted an annulment on the grounds

she was never legally married. Porumbeanu’s real wife Helma and their daughter Georgette

attend the hearing to support Gambi. Gambi says Porumbeanu was a “leech, a

letch and a drunk”. He is described as an “unfit human, an unfit father”. It is

alleged he was constantly drunk, that he got a 17-year-old maid pregnant and

forced her to have an abortion, and that he tried to invade the rooms of

Gambi’s visiting female friends.

July 1, 1965: Gambi, 24, marries $11,500-a-year New York

policeman Thomas F. Gallagher, 32, in Clinton. Gallagher, born in Auburn the son of a

former Major League baseballer, Thomas Gallagher, is a state police

investigator. They are to honeymoon in Ireland. The best man at their wedding

is Gambi’s brother Doug, who introduced the couple. The maid of honour is

Doug’s future wife, Sammy Jane Dowling, from Fort Worth, Texas. Doug and Sammy

divorced in 1984.

April 22, 1966: Tom Gallagher settles a $1 million Supreme Court action against the Hearst Corporation for

publishing a rumour that his marriage was in trouble. A retraction, headed "Gamble is a Happy

Wife" was published in the New York Journal-American. It said, "Gamble

Benedict Gallagher, from every report, is enjoying happy married life with her State Police Investigator

husband, Thomas F.Gallagher and their two boys by Mrs Gallagher's former

marriage. Last December. Gamble became a Roman Catholic and regularly attends Mass with her family." The retraction was

given the same prominence as the original story, headlined "What Now,

Gamble?", published the previous October. In that article it was stated that Gambi "is back with her lawyers for a change". It also said that she and her husband

"have been squabbling ..."

July 11, 1967: Gambi gives birth to a third son, Grant, in

Utica.

1972: Porumbeanu sues American Express for $50,000 for allowing

Gambi to open 19 packages of his belongings sent from Rome at the time of their

1963 separation.

August 9, 1974: Gambi is living in Barneveld, New York, with husband Tom and their

sons Grant, 7, and Courtney, 4, as well as her two sons from her first

“marriage”, now known as George and Gregory. Gallagher retires from the police

force, aged 41, to become a teacher at the Valley Forge Military Academy in

Wayne, Pennsylvania.

1985: In late 1985 Chief Thomas F.Gallagher was Pennsylvania's top

criminal investigator. He was director of the Bureau of Criminal

Investigation in the State Attorney General's office, having formerly been head

of the Criminal Justice department at Valley Forge Military Academy and Junior

College. Gallagher had lectured at INTERPOL conferences and served as a

security consultant to the Winter Olympic Games in Sarajevo in 1984.

September 23, 1988: Andrei Porumbeanu dies in New York. aged 63.

Sometime between August 1974 and January 1999: According to the National Society Magna Charta Dames and

Somerset Chapter Magna Charta Barons, as at January 8, 1999, one of its

members, “Mrs Thomas F.Gallagher (Gamble Benedict Sharpe)”, was deceased. Gambi would be 71 now if this was untrue.

August 6, 2009: Ileana Bulova-Lindt dies in West Palm Beach, Florida, aged 89.

.JPG)

+-+Copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)